Michigan asks US Supreme Court to act in Asian carp flap

Loading...

| Chicago

The state of Michigan is asking the US Supreme Court to intervene to prevent Asian carp from further infesting a historic canal that connects the Mississippi River basin to the Great Lakes.

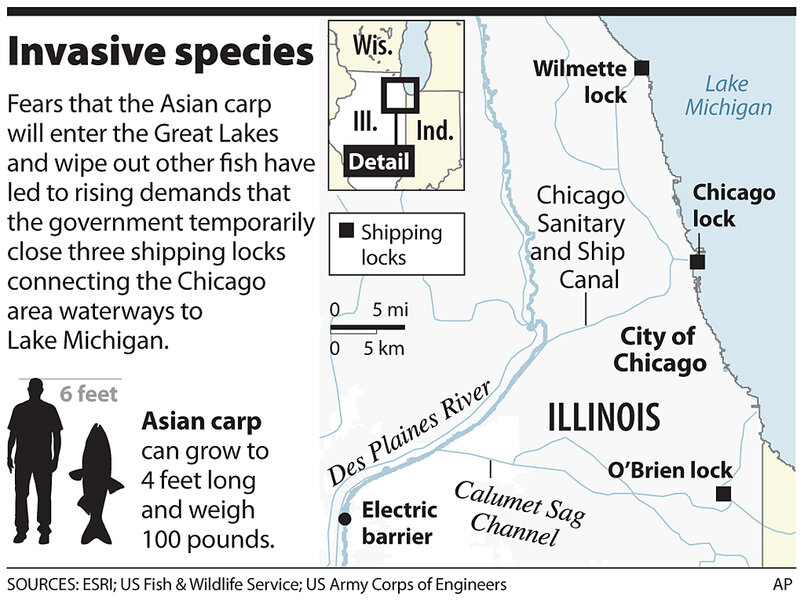

The lawsuit, filed Monday, follows the discovery in early December of a single Asian carp about six miles from the Lake Michigan’s Chicago coast. The fish, a bottom feeder, is presumed to have entered the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, which links Lake Michigan to a tributary of the Mississippi River. The species has gradually migrated northward from Mississippi and Arkansas, where the fish were introduced in the 1970s to help clean catfish farms.

The discovery of the one Asian carp by the US Army Corps of Engineers, the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago, and the Illinois Department of Natural Resources raised alarms in neighboring states because the fish has never before been found this far north. Neighboring states say the huge carp, if they reach Lake Michigan, will destroy the ecosystem of the Great Lakes and, along with it, the lakes' $7 billion fishing and tourism industries.

“We view it as a do or die if the carp gets to Lake Michigan,” says Michigan Attorney General Mike Cox, who filed the lawsuit Monday. “We hope the courts will attend to the request with the same urgency that we do.”

A bid to expedite the case

To get the case to the Supreme Court as quickly as possible, Mr. Cox summoned three separate 1929 complaints pitting Wisconsin, Michigan, and New York against Illinois, charging the canal unnaturally diverts water away from Lake Michigan for sewage and sanitation purposes. The first request of his petition is the immediate lock closures at the O’Brien Lock and Dam and the Chicago Controlling Works.

If the former decrees are not amended, Cox says, he will file a new case charging various state and federal agencies with allowing pollutants, namely the carp, to contaminate the Great Lakes system. He is seeking support from surrounding states as well as environmental groups and regional native American tribes. “We cast a wide net, and all those entities are as concerned as we are,” he says.

The Michigan lawsuit is the latest in proceedings that stretch back almost 100 years in a struggle to regulate the Illinois canal, says Thom Cmar, an attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). Those proceedings have resulted in rules of operation intended to placate all sides but have not fully and permanently addressed the environmental hazards that the canal’s artificial flow continues to create, he says.

“The status quo is no longer acceptable,” says Mr. Cmar, who says the immediacy of the case makes it “an unprecedented situation.” “We’re hoping Michigan will light a fire” to get other states involved in the fight, he says.

Economic 'disaster'?

Closing the canal, even temporarily, will create economic disaster for the barging industry and the loss of 400 jobs, says American Waterways Operators (AWO), a trade association representing the tugboat, towboat, and barge industry. Its data show that products ranging from asphalt to coal that are shipped through the Chicago canal generate more than $30 million in revenue for the industry.

Shutting the canals to keep out the Asian carp “is a false choice,” says Lynn Muench, senior vice president of regional advocacy for AWO. The species can enter the water “in other ways beyond navigational channels.”

The lawsuit seeks a permanent closure of canal waters from Lake Michigan. One solution for the barging industry, NRDC's Cmar says, is to create a port connecting lake commerce with canal commerce, but with a separation wall preventing water from flowing from one side to the other. Barges from the canal side could offload goods to barges on the lake side for their continued voyage, or could transfer the goods to trucks or trains.

“We need to have a real debate on this to figure to what is at stake,” he says. “Only through creating this process based on facts and science will we come up with solutions that will take all interested into account.”

But transferring barge cargo to alternate transportation will only create unnecessary congestion and pollution – namely, 1.3 million more trucks or at least 302,000 more rail cars per year, says Ms. Muench. “At this point in our economy, people need to be brought up to speed on what this means,” she says.

----

Follow us on Twitter.