Does space need air traffic control?

Loading...

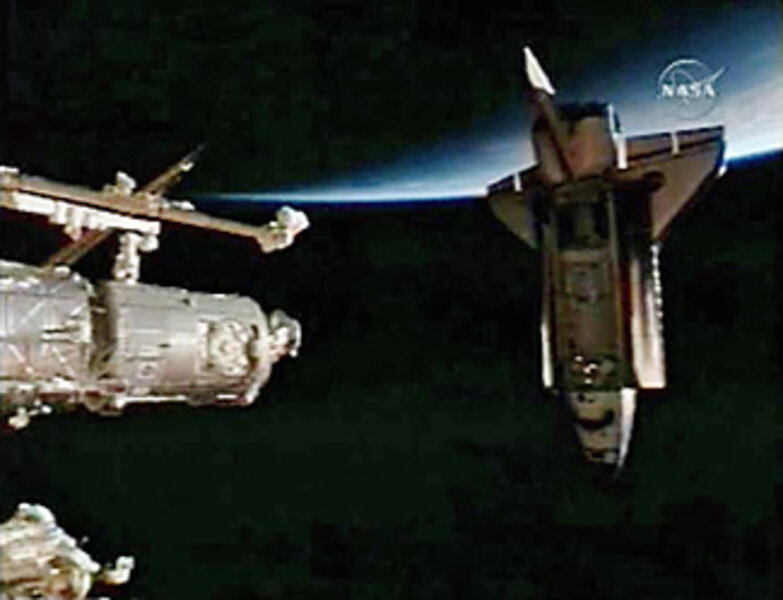

The way Kirk Shireman describes it, the International Space Station is fast becoming the O'Hare International Airport of low Earth orbit.

The shuttle Endeavour docked with the station Wednesday night, and shares it with a Russian Progress resupply craft that arrived in February. The shuttle is slated to leave March 24. Europe's robotic cargo ship arrives April 3. Four days later Progress leaves, while a Russian Soyuz craft arrives April 10 for a crew swap. And next year, Japan is expected to add its automated resupply ship to the mix.

"That's quite a traffic flow. We're thinking about launching an air-traffic controller soon to keep it all straight," quips Mr. Shireman, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's deputy program manager for the International Space Station.

His jest, during a recent prelaunch briefing, nevertheless highlights what several specialists see as an emerging issue for spaceflight in the 21st century: a need to overhaul the way people manage traffic in space – from human-tended craft and satellites to the long-standing problem of space debris.

Some say it may be time to set up an international body similar to the International Civil Aviation Organization to establish common standards and practices. Others suggest that individual nation-to-nation agreements could be enough.

Whatever the approach, aerospace traffic management "is getting to be a hot topic," says Ben Baseley-Walker, a consultant for the Secure World Foundation, a space-policy think tank based in Superior, Colo. Meetings on the subject that drew a few dozen academics two or three years ago are now drawing crowds of nearly 200 from around the world, he says. And several of the newer attendees are wearing military uniforms.

The reason: As more countries get into the space game, more spacecraft – manned and unmanned – will flit around Earth. "Increases in activity lead to increases in objects, and, therefore, increases in space debris. It's not a question of if, but when," says Mr. Baseley-Walker.

Close to Earth, a crowd

Outer space may be big, but the regions around Earth where satellites or humans can linger are relatively few. Low earth orbit, sun-synchronous orbits, and geosynchronous orbits are the current hot spots. And within those broad categories, there are preferred locations. Even at the moon, things are getting busy. In October, NASA is scheduled to send its Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to the moon, where it will join a lunar satellite from China and three from Japan. Earlier this week, NASA announced it was interested in setting up international science "nodes" on the moon – research platforms or vehicles that eventually could be linked via a moon-orbiting communications satellite.

Back around Earth, space junk – from paint flecks to chunks of spent rocket stages – share orbital space with satellites, the shuttle, the space station, and, eventually, any privately financed space stations and orbital space tourists.

Then there are the prospect of hybrids: Suborbital tourist flights and intercontinental transport that flirt with space as they travel. These will add their own unique air and space traffic issues.

Meanwhile, the risks to orbital regions are growing. Experts cite China's antisatellite test last year as one example. The target, a one-ton weather satellite, circled Earth in a region where other weather, remote-sensing, and spy satellites commonly roam. Its destruction generated an estimated 900 pieces of debris that will remain in orbit for up to a century.

By some estimates, it would take only 10 to 12 such "tests" to render the region useless to everybody. Remaining debris from the satellite the US Navy shot down late last month, by contrast, will be gone in a matter of months since the Navy's missile hit it at a lower altitude.

One challenge to setting up a more effective system is agreeing on a definition of where traditional air space, with its national sovereignty, leaves off, and outer space, a global commons, begins. By tradition, the boundary is 100 kilometers up, or some 62 miles. But there is no legal or scientific definition to support that, analysts say. Most spacefaring nations buy into this working definition. But in 1976 a handful of countries that lie along the equator signed the Bogota Declaration, which asserts that their "airspace" – hence their sovereignty – reaches all the way up to the geosynchronous-orbit slots some 22,300 miles directly over their countries.

A system to avoid collisions

Sorting through this and other issues including national security will be challenging, acknowledges Theresa Hitchens, director of the Center for Defense Information in Washington. She says a new aerospace traffic-management scheme should include mandatory notification and consultation when a satellite operator – government or private – plans maneuvers. In addition, countries need to establish an international database on satellite and debris orbits. Currently, the US Air Force has an exhaustive database, but getting information from the Air Force can be slow and its budget for data-sharing waxes and wanes. Countries should also be required to send out a global notice when they plan to place their satellites into graveyard orbits or allow them to reenter Earth's atmosphere and burn up, she adds.

"The real crucial thing is some system for collision avoidance and a process to ensure that people don't run into each other," she says. It may look like space leaves plenty of room to maneuver, but objects are moving so fast that once they swing into sight, it's too late.

To be sure, some efforts at sharing data and coordinating activities are appearing now, although on an ad-hoc basis. Ms. Hitchens notes that when China sent up its Taikonauts, for instance, the US Air Force shared its orbital-debris data with the Chinese.

Tentative cooperation

Moreover, with this shuttle mission and the arrival of Japan's space-station hardware – as well as the launch of Europe's first automated cargo ship – six control centers in five countries are linked for the first time to coordinate activities around the space station. In the private sector, several of the world's major commercial satellite operators, including companies such as Inmarsat, Intelsat, Loral, and Eutelsat, reportedly have been working over the past 18 months to develop ways their operators can exchange data on orbits and maneuvers without exposing trade secrets.

Such approaches may serve as valuable proving grounds for more effective aerospace traffic-management techniques. "The technical issues are not difficult," says Baseley-Walker. "The key issues are political."