Tornadoes tear through Southern states, but new alerts saved lives

Loading...

| Atlanta and Boston

The devastation in tiny Atkins, Ark., following a deadly spate of winter tornadoes, hit residents hard as rescuers picked through the rubble of churches and homes Wednesday.

"It's just terrible," says J.L. Austin, a local barber, in a phone interview.

The Super Tuesday tornadoes killed at least 48 people, including four in this town. But a year-old siren system in the rural Arkansas county may have saved lives. Sirens blared 20 minutes before the tornado hit, enough time for Mr. Austin and his family to find shelter in his brother's basement.

With better weather monitoring and the wider use of sirens and other warning systems, the number of tornado deaths per million Americans has been decreasing in the United States for decades. Yet the tornadoes that swept the mid-South served as a reminder, experts say, that better public education and new technology, such as text-messaging on cellphones, could augment traditional warning systems.

Meteorological trends seem to favor efforts to accomplish that. The frequency of the strongest twisters – F-4 and F-5 tornadoes, whose destruction is the most difficult to mitigate – is on the decline, even as the overall number of weaker storms has increased.

"In an F-4 or F-5, there's little anybody can do," says Ben Aguirre, a preparedness expert at the Disaster Research Center in Newark, Del. "We have to worry about more forgiving sorts of storms."

The sheer power of the front produced the most powerful breed of twisters, some of which may have overpowered even well-prepared residents, experts say.

"This was kind of an early season event, and I think it caught people off guard a little bit," says Chris Wikle, a weather statistician at the University of Missouri.

Not since April 1998, when tornadoes ripped through Alabama and Georgia and caused 48 fatalities, has a string of storms been as deadly.

The Southeast is no stranger to winter tornadoes, notes Harold Brooks, a scientist at the National Severe Storms Laboratory in Norman, Okla. Last year, three tornadoes touched down along a track through east central Florida in the early morning hours of Feb. 2. They carved a path of destruction some 70 miles long. In Lake County, 21 people were killed. Then on March 1, a tornado outbreak struck southern Alabama killing 11. But to have an outbreak this severe in this part of the Southeast in the first week of February "is pretty rare," he acknowledges.

Since 2000, only 8 percent of tornado deaths have occurred inside the traditional tornado alley that runs from Texas and Oklahoma to Kansas, Nebraska, and South Dakota, according to the Storm Prediction Center, also in Norman. In 2007, the vast majority of tornado deaths came farther east, in the mid-South, ranging from Alabama to Kentucky.

The outbreak was triggered by the mix of a very powerful winter storm system moving across the central US – not unusual for his time of year – and an unseasonably warm, moist, and unstable air mass over the Mississippi Valley in its path, says Greg Carbin, a meteorologist at the Storm Prediction Center. "When you look at these conditions, they are clearly one or two months ahead of schedule" compared with a typical year, he says.

Forecasters at the Storm Prediction Center got their first inkling that Tuesday had the potential be a violent weather day some six days before as they looked at the results from their medium-range forecasting model. As the storm system tracked across the country, the potential grew. By the time the system was 12 to 18 hours west of the stricken region, they had started to issue maps to local forecast offices identifying the regions with the highest likelihood of experiencing severe weather capable of spawning tornadoes.

"People were very well-warned," says Laura McPherson, spokeswoman for Tennessee Emergency Management. "We had very warm temperatures the day before and for the past few days meteorologists have been warning that storms were very, very likely."

One challenge for local forecasters who issued specific tornado warnings – and for residents who had to respond to them – was the speed with which the violent, potentially tornadic thunderstorms were traveling. If a storm moves at a somewhat sluggish 20 miles an hour and forecasters get spotter reports of a funnel cloud or see its telltale signature on their radar while it's still 10 miles out, they can post a warning that gives people a 30-minute heads up. But if a storm roars along at 60 miles an hour, that leaves 10 minutes between a warning and the storm's arrival.

For this system, surface winds were cranking along at between 50 and 70 miles an hour, with far higher speeds aloft. Preliminary estimates suggest these winds pushed individual storm cells along the front at from 35 to up to 70 miles an hour, Mr. Carbin says. And any small error in estimates of a storm's track can rapidly multiply, adding an additional challenge to issuing tornado warnings to the right place at the right time.

Rural Macon County, Tenn., got hit the hardest, with at least 10 fatalities and major state roads still impassable Wednesday morning.

The federal government doesn't map siren coverage in the US, and private siren manufacturers don't give out specific sales information. But they do acknowledge that the use of siren systems, often accompanied by cellphone or e-mail warning systems, is growing throughout the US.

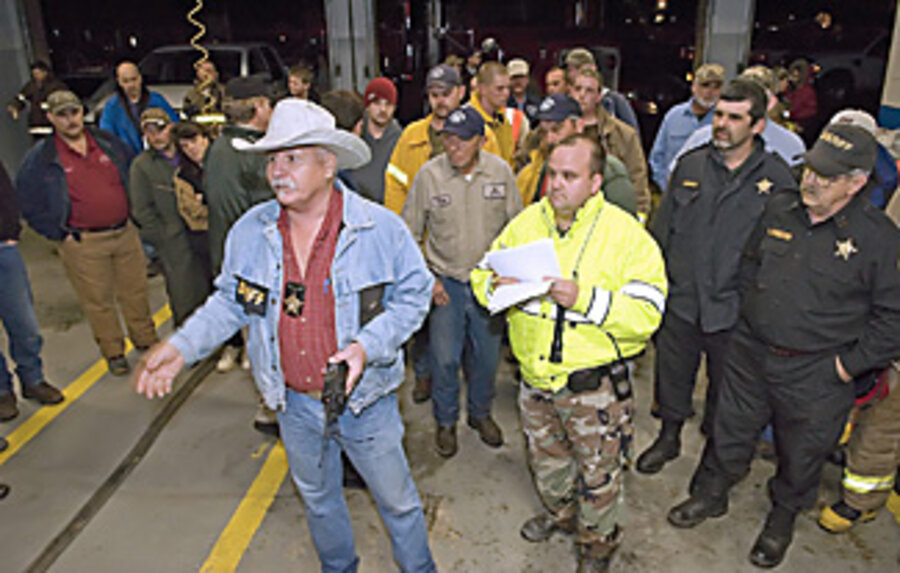

Urban areas tend to be well covered by sirens. It's more difficult for rural areas to raise tax money to purchase them, especially since more are needed to cover vast areas, says David Freeman, the emergency management director of Pope County, which includes Atkins.

Atkins received six used sirens for free last spring when Entergy Arkansas upgraded the warning system at a local nuclear plant. "I've talked to a lot of residents who credit those sirens for saving lives," says Mr. Freeman.

Professor Aguirre says what's lacking most is practical experience from storm survivors. He points to one of the most controversial items: Whether those in the path of a storm should try to escape in a car. Some experts warn against it; others say it needs to be explored.

"We have no way ... to ask people systematically what they did in their own microenvironment to protect themselves," says Aguirre. "We don't have any kind of sustained research effort to prove what strategies seem to work and which don't."

In Atkins, a new church and dozens of homes were destroyed. But many people told Austin, the barber, that they felt well informed about the looming front.

"They're pretty good about sounding the sirens," he says. "We're real thankful."