Burke, Twain, and the economy of truth

Loading...

Our vocabulary for ways of saying things that are not true is abundant. Our vocabulary for ways of failing to say things that are true – not so much.

We have lie, short and sweet, a headline writer’s dream. We have fib. Usually too slangy for print, it nonetheless captures the intensity of a child’s nascent sense of injustice: “When he said his dad played for the Patriots, he fibbed!”

There’s prevaricate, rooted in Latin words meaning “to step out of line” or “to walk crookedly.” The list goes on.

On the other side is this idiom: economical with the truth. It sounds like something you’d hear from the pursed lips of a certain kind of lawyer. “Yeah, I heard what he said,” you might say afterward. “But what did he mean?”

Good question.

The Oxford Dictionary of Modern Quotations traces the phrase to the British politician Edmund Burke (1729-96). He didn’t actually use those words. He did refer, however, to “an œconomy of truth ... a sort of temperance, by which a man speaks truth with measure that he may speak it the longer.”

Burke’s idea seemed to be that parceling out one’s utterances of “truth” carefully (“with measure”) would give one more time to remain active in the public conversation, able to “speak ... longer.”

For an elected politician or a civil servant, fewer utterances of “truth” mean fewer occasions to offend with unpleasant fact, or to face the temptation to lie and run the risk of being caught out. But if Burke considered the “œconomy of truth” a good thing, the idiom “to be economical with the truth” signified a bad thing.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “to be economical with the truth” thus: “to be partially or wholly untruthful; to (deliberately) mislead; to misrepresent the facts of a matter.”

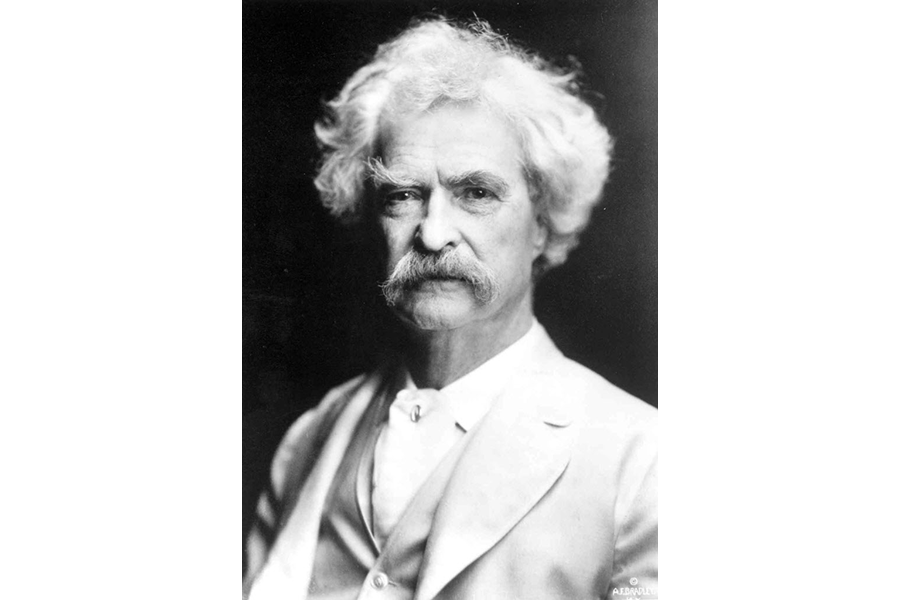

Some dictionaries flag the phrase as “humorous.” Mark Twain, for instance, played off it as a bit of a joke.

A chapter-head epigram in his 1897 book “Following the Equator” reads, “Truth is the most valuable thing we have. Let us economize it.”

Then he quotes some fantastical directions for finding Samoa: “You go to America, cross the continent to San Francisco, and then it’s the second turning to the left.” Twain was obviously having fun.

“Economical with the truth” turned out to be not very funny, though, when it acquired renewed currency during the late 1980s.

The British government wanted to block publication of “Spycatcher,” a high-level spy’s controversial memoir. When a British official being cross-examined in an Australian courtroom in connection with the effort acknowledged someone’s having perhaps been “economical with the truth,” he evidently thought he was delivering a laugh line.

Australian journalist Bob Ellis reported that the official paused to await a response. But no laughter was heard.

The cross-examiner went on to nail the witness for his duplicity. The British government lost its case, and the cross-examiner, Malcolm Turnbull, is now prime minister of Australia.