A wordless welcome to rural Italy

Loading...

The other day, Dino, our neighbor across the road, saw me in front of our new home in Italy and called out, “Good evening!” His English, though limited, is much better than my all-but-nonexistent Italian. “You OK?” he asked.

He had greeted me before, usually with a Buongiorno (good morning) or a Buonasera (good evening). Once, seeing him trying to fix a tall street lamp, I’d held a ladder for him to climb. But that was pretty much it for us: a general air of cordiality prevailing, nothing more.

I’d just concluded 46 years living in New York City, where you can live next door to someone for 10 years without saying hello, much less introducing yourself. But now I’m living in a town in Italy’s Puglia region, and everyone here except my family is a stranger. And, residing in the countryside as we do, I’ve started to feel pangs of rustic isolation.

This moment therefore seemed an opportunity to get to know Dino a little. I could have stayed behind our gates to talk with him through his gates, as if from cell to cell in a prison. But instead I unlatched our front entrance and crossed the road toward him. I then recalled how someone had once said of Italians that if you take half a step toward them, they will take a full step toward you.

And that’s what happened. I stood in the street talking with Dino and his wife, Grazia – I in English, they in Italian. One minute later they invited me in for a tour.

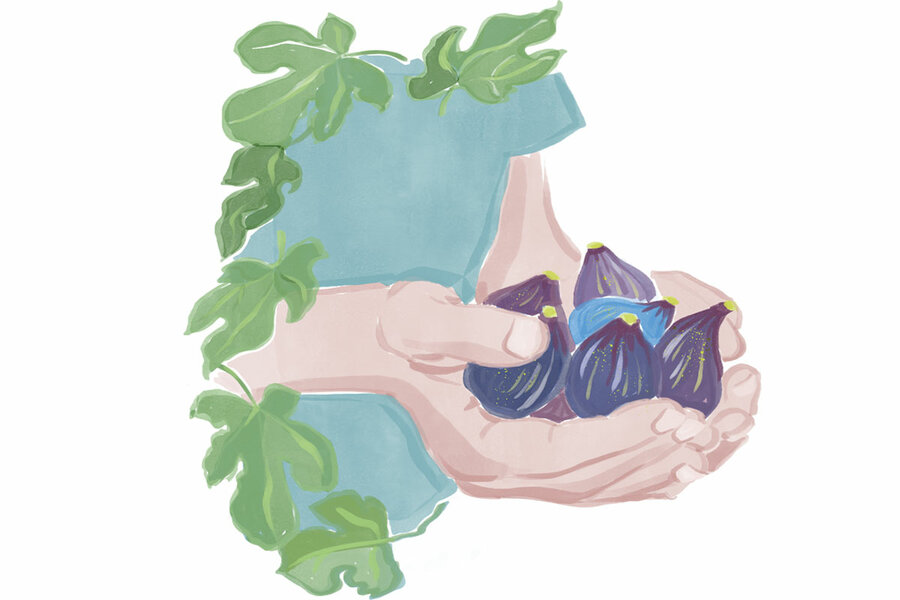

Here, for starters, was a fig tree, thick of trunk and branch, more than a hundred years old, bearing ripe figs. Dino plucked a few of the plump fruits and handed them to me. My cupped palms were soon brimming with figs.

“You can eat these?” I asked. “Sì,” he said. Dino held a fig in front of me, tore it in half, and popped one-half in his mouth. He handed me the other half and signaled for me to follow suit, and I did.

“Delizioso!” I declared.

I once saw a wonderful documentary about Gregory Peck. In it, the older actor travels to Ireland to meet his new grandson. But first, wandering a field, he happens upon a fig tree. He picks a fig and eats it with obvious delight. To me, the scene captures the sweetness of life and how such sweetness is all around us – if only we’d bother to reach out and taste it.

Dino and I repeated this sequence with trees bearing plums and walnuts, too – he plucking, I sampling. He showed me around his property, ambling past a swimming pool, a trellis, and a zip line he had built for his adolescent grandchildren. We sat at a table under a canopy of pine trees, and Grazia brought out a bowl for all the fruits and nuts for me to take home.

Despite our differences in language – neither of us knew many of the other’s words – nothing important was lost. I understood the wave of his hand inviting me to enter his property. I understood being handed figs straight from his own tree. Both of us understood all we needed to understand: that now we were true neighbors.