In New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward, our garden grows a sense of place

Loading...

| New Orleans

Cynthia loved the house: an old turquoise cottage with yellow trim in New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward. But it was the vacant lot next door that caught my eye. The seller told us it wasn’t an either-or deal. Our option was to buy both properties or move on.

We bought both. We’d eaten a lot of potatoes to save up for the largest purchase of our lives. It was the cheapest home for sale in our neighborhood.

“Y’all are going to need a bigger lawn mower,” our real estate agent joked.

Why We Wrote This

To work in a garden is to attract neighborhood onlookers. And as plants grow, so do connections with the community.

We needed a wheelbarrow and a shovel, too.

The lot was overgrown with tall grass and shrubby trees. It was thick with bits of trash, urban tumbleweeds thrown about by the wind coming off the Mississippi River.

Growing food is a rite of passage in rural East Texas, where I grew up. Heads of households feed their families: Memmaw always had homegrown tomatoes ripening on a windowsill. The same is true for my Uncle Ray. My cousin Joe is building out a 60-acre farm back home. My dad is back to keeping a garden, and even dug a fish pond. Now I had a household of my own to feed. And because I tend to be zealous, I went big.

I ordered a dump truck-load of topsoil – 6 cubic yards. The pile came up to my shoulders. One order became three, then six: 36 cubic yards of good earth.

I built raised beds, stacking salvaged bricks and concrete blocks: six 9-foot-by- 6-foot beds. Then a bed 25 feet square, plus two more, each about 15 feet by 20 feet. Three-quarters of the lot was now garden.

As I dug in the beds, each shovelful brought up bits of the Lower Ninth Ward’s past, before Hurricane Katrina profoundly changed it; pink bathroom tiles; a rusty spark plug; slabs of concrete on which a house had rested. Memories and secrets rose from the soil.

There were other discoveries as well. Working outside, I was available to my neighbors. I found conversation, friendship, and community.

Roy, our block’s unofficial groundskeeper, had been mowing folks’ yards for decades. He told me about the couple who’d owned our home, and how they’d been the neighborhood’s peacekeepers. I met “The Praline Lady,” her preferred title, as she drove her motorized wheelchair around the block, hawking homemade candy. Athelgra was a member of a famous musical family. (The Dixie Cups’ big hit was “Chapel of Love,” in 1964.)

Recently, our neighbor Will walked up to ask what I was growing. I pointed to the lettuce, mustard, and collard greens. I invited him to help himself. He did. Katrina came up.

Will pointed to the newly built house across the street. When we first moved in, what was left of a Creole cottage had been there. It was torn down not long after – the source of the bricks for edging my beds. Will told me he’d slept in that cottage after Katrina. He’d had nowhere else to go – nowhere that was dry.

Our neighborhood’s scars are still evident, mentally and physically. Abandoned buildings line our main corridor. Gunshots ring out at night, though they seem to be receding as time goes on. The Lower Ninth is recovering, but without many who once called it home.

In the 1950s and until Katrina in 2005, the Lower Ninth had one of the nation’s highest rates of Black homeownership. Only about one-third of the Lower Ninth’s Black population returned. Many homes and lots were sold at tax auctions. Millennials like us are moving in now.

I know from my upbringing that sharing homegrown produce helps to sow unity in a community, and that was another motivation for the garden: produce as olive branch.

We’re 18 months into the project. The lot has been tamed. It’s an actual garden, almost paradise.

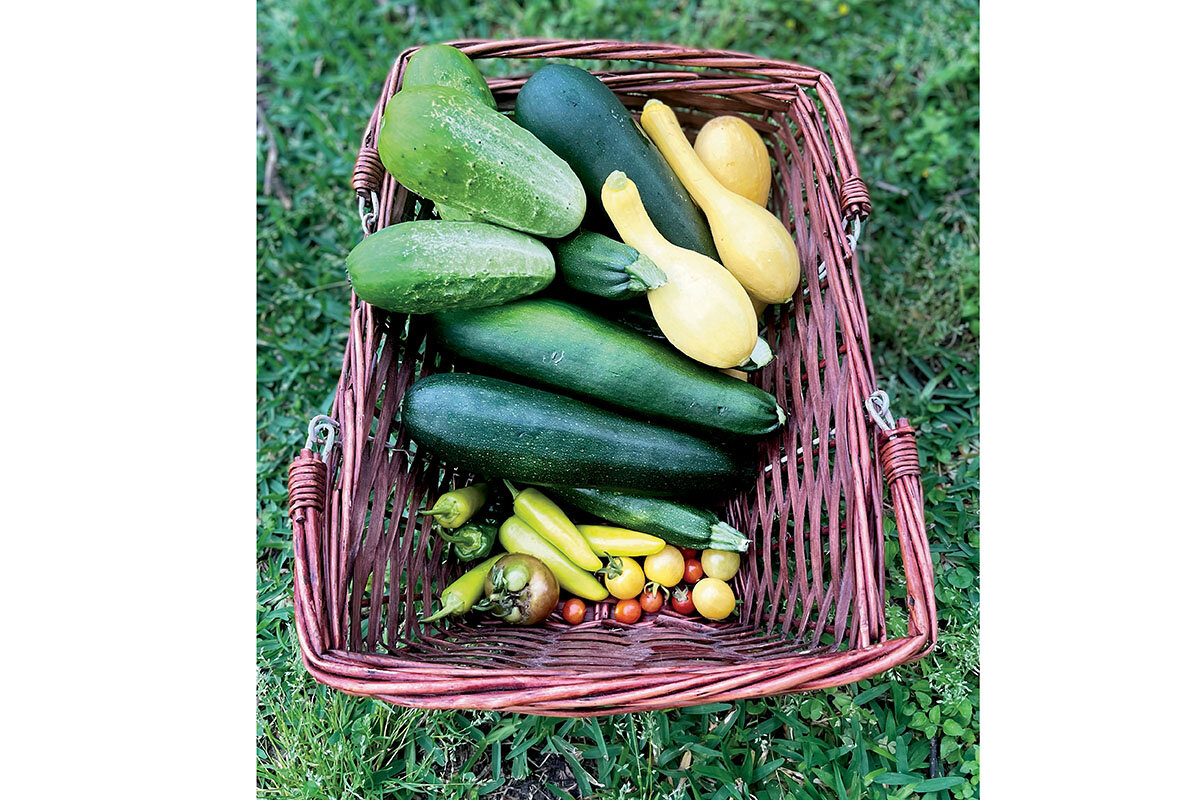

I stand in our kitchen, looking at bags and bags of food from the garden, and note our severe lack of freezer space. “What are you doing?” I ask myself with a laugh. I don’t have a good answer yet.

But I do know that the garden is not just about growing food for us or our neighbors. It’s about growing a sense of place and home. It’s about my growing as a person, too – the new head of a household.

Eighteen months ago, Roy would have passed us by on his bicycle, instead of stopping to encourage me as I sweated, shovel in hand. I would have been just another face to The Praline Lady. I would have never known Athelgra is a famous musician. Without our big garden, I wouldn’t have come to know the weight my neighbors still carry from Katrina. I would not have understood my new community, my new family in New Orleans.