Our refrigerator’s door to a culture

Loading...

Actually, I wasn’t even the one who took the picture of our fridge in Zimbabwe. Our secondhand refrigerator has sawed-off legs so that it fits snugly under a shelf in our stone-floored kitchen. More often than not, it sits in a puddle of water occasioned by frequent power cuts.

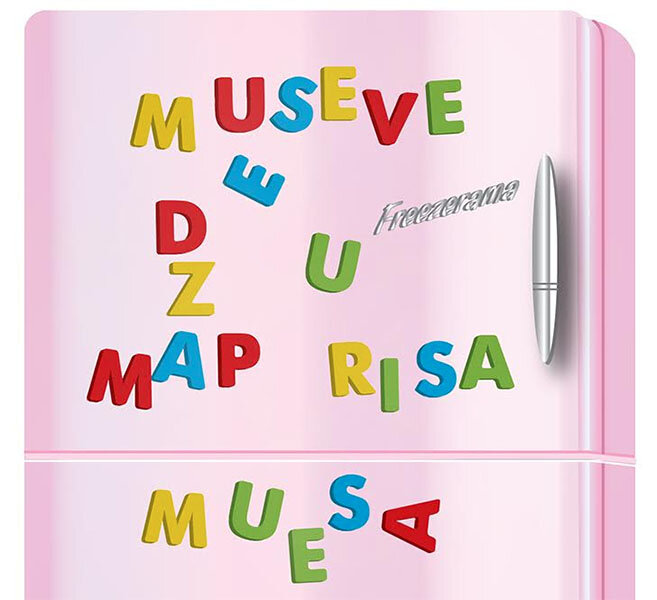

Taken one evening last October, the photo wasn’t of the puddle. It was of Sam’s Shona homework: lists of words and phrases in Zimbabwe’s ethnic Shona language that our then-10-year-old was trying to memorize.

Sam snapped the picture, amused at the way we’d effectively papered our fridge with words. (We’ve never managed to paper our living room, where there’s still a crack in the pink paint from the earthquake that rattled our eastern border city in 2006.)

In an idle moment, I posted the photo on Twitter, and the reaction was immediate – and heartwarming.

Sam’s (slightly blurry) picture was retweeted and commented on. Those comments were retweeted by other Zimbabweans, starting with a long drawn-out “Cooooooool.” Some sent me messages of support and approval.

“Awesome! We shld all learn each other’s culture for integration. Separateness caused a lot of conflicts in Zimbabwe,” one local told me.

“If only my people could see this,” wrote another.

One Twimbo – as Zimbabweans active on Twitter call themselves – thoughtfully enlarged Sam’s photo and found a gap in the list of meanings. Sam and his dad had not filled in the meaning of “dhiri.”

“It means ‘deal,’ ” he messaged me.

In the ensuing months, as the words on the fridge changed and the Shona phrases Sam can say have lengthened, I’ve thought about that photo and what it meant to the Zimbabweans who saw it.

Some even sent me encouraging messages weeks after I first posted the photo.

The 9 million people who speak Shona are – mostly – extremely proud of it. It’s not the only ethnic language spoken here. Ndebele is the other major one, spoken in the south of the country. There are 13 others.

Many here worry that Zimbabweans don’t value these languages enough. They lament on Twitter that Shona-

speaking parents don’t mind if their children can’t speak their mother tongue well – though it’s a compulsory subject in all schools.

The other often-voiced complaint is that visitors and immigrants don’t bother to learn even a few words of Shona.

Ironically, it doesn’t help that so many Zimbabweans are accomplished linguists, speaking English (Zimbabwe’s main language for business) perfectly.

Soon after Sam started school, all parents – black and white – were summoned to a meeting with the Shona teacher, Miss K.

“I love my language,” she said passionately by the light of a candle (there was a power outage). “I want your kids to like it, too.”

So Sam’s father and I committed ourselves to improving our own Shona, which was halting at best. When Sam was born, we gave him a Shona middle name to show how much we loved Zimbabwe and its culture.

Now we realized that our son had to see us learning, reading, and speaking Shona before he would seriously apply himself to it.

It’s not been easy. Growing up in England, I learned French and German at school, plus Italian and a little Spanish later. Picking up Shona now, with its very different linguistic roots and structure, is hard. But it’s important.

Before he starts work in the morning, Sam’s dad labors with a Shona dictionary and phrase book, drawing up new lists of words and phrases for Sam to learn. Trussing Sam’s little sister up in her pajamas every night, I keep half an ear on the after-supper language lessons. Reaching for the milk or a scoop of homemade baobab sorbet, I find myself glancing at the words of the day on the fridge. “Dhongwana,” I see, means “baby donkey.” “Kumba kuri kufaya” means “Things are fine at home.”

Last week, as I bargained for thick winter sweaters at the flea market, I heard a vendor say of me to her neighbor: “Anogona chiShona.” It means “She is capable of speaking Shona.”

I hugged the words to me, carrying them home like a gift to present to the rest of the family.

I don’t speak Shona well. Not yet. Sam and his dad are ahead of me, and they still find it difficult, too. But we’re all trying.

The fridge helps, of course.

Glossary of Shona words

(MANG-wan-ah-nee): Good morning

Chisarai (CHEE-sah-rye): Goodbye

Ndapota (in-DAH-por-ter): Please

Mazviita (MASH-vee-tah): Thank you

Hupenyu imhindupindu (hoo-PEN-yu

IM-hin-doo-pin-doo): Life is a roller coaster.

Kumba kuri kufaya (CUM-bah COO-re

coo-FIE-ah): Things are fine at home.

Ndinogona kutaura chiShona zvishoma chete (in-DEE-no-GONE-ah COO-tau-OR-rah chee-SHOW-nah JEE-show-ma chair-tee): I only speak a little Shona.