When does a tennis fan slip over the line into a fanatic?

Loading...

Not to be presumptuous, but I hereby christen the first decade of the 21st century the Time of Rehab.

Hollywood stars, politicians, and athletes are marching through treatment programs for an ever-widening array of "addictions." Not far off, I predict, are treatment plans for failure, rehab centers for the overly competitive, and multistep recovery programs for excessive candor or obfuscation, depending upon which side of that line you habitually fall.

So, as I flew recently into Palm Springs, I started wondering about myself. Was the thing that brought me here, into this desert of dry gullies, palm trees, and a street called Frank Sinatra Drive, veering out of control?

It seemed harmless enough. I was here for a deep dunk into big-time tennis, a sport I have loved for almost all my life as both a player and fan. Which brings me to Indian Wells BNP Paribas Open, one of the world's major tennis tournaments, boasting the largest attendance of any tennis event save the four Grand Slams. I was here to "cover" the tournament as a reporter, which I did with unblinking attention and devotion. But let's be real. I didn't have to cover the tournament. I did it by choice.

So for five full days I woke up, took a bus to the splendid Indian Wells facility, and didn't return home for about 10 hours.

Going into this full-court marathon, I wondered if seeing a sport up close like this might actually be self-corrective. Over a career of 30 years in journalism, I met sports reporters who told me they entered the field out of a love or interest in athletics, only to end up somewhat disillusioned by the excesses of money, ego, and bad behavior that seem to come with modern-day professional sports. In short, for them, the thrill was gone.

Would I go home broken, in a good way, of this – let's be careful here – longstanding interest? Was it just an interest, or something more sinister, an obsession? OK, there, I've said it.

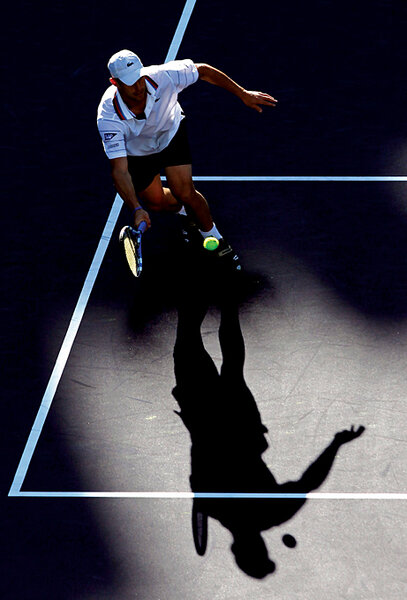

What do you call a person who swoons when Roger Federer flattens a backhand down the line? Or when Andy Roddick goes down the "T" with a 134 m.p.h. serve. Or when Rafael Nadal, stretched wide, rips a backhand cross-court passing shot from an improbably off-balance position. Or when waif-like Justine Henin strokes a one-handed backhand that is as poetic as anything in verse.

Someone once called tennis civilized boxing. It is one of very few sports that pits player against player, no cushion of a team, no way to collectively share a defeat. There are plenty of individual sports – swimming, golf, and track and field – but in tennis it is one individual against another. It's not about your own individual time or score. It is about asserting your own game against your opponent's game.

Indian Wells BNP Paribas Open is an extraordinary venue, and by all accounts exceptionally popular among the players because of the generally relaxed nature of the event. Up around the media center, it is common to look over your shoulder and find current and former players mingling.

Outside the main stadium there are practice courts, where fans stand directly behind a Federer, Nadal, or Roddick as they take a practice session. Alongside those practice courts is a large lawn, where players spend downtime playing soccer or throwing around a football. By the way, world No. 2 Novak Djokovic can throw a spiral.

That lawn area has only a short picket fence, meant to provide a gentle separation between fans and players, and that line is respected. After a hit, many of the players wander over to the picket fence and sign autographs. There is a relaxed proximity between players and fans that is hard to imagine in many other professional sports. And if there is any lesson here, it just might be that lowering walls will actually improve fan behavior.

As I walked an outer hallway during a game change, I noticed a looming presence over my shoulder and turned to see Lindsay Davenport, absorbed in her handheld electronic device. On my first day in the dining hall, a stoic Ivan Lubicic sat alone, a plate of finished pasta before him, staring at the TV monitor and an ongoing match. If I had known that he was going to shock us all by winning the tournament, I would have asked him in advance how he was going to do it.

Players are required to meet the press within an hour of their matches and those brief encounters were fascinating. Andy Roddick is sharp and collegial. Rafael Nadal is disarmingly child-like, particularly compared with his on-court demeanor. Andy Murray is relaxed and laconic. Roger Federer is confident and direct. Federer lost early in the tournament, after squandering three match points. And he lost that match by losing a third-set tiebreaker. When asked by a reporter at the press conference if he played a poor tiebreaker, he answered with some irritation: "I should never be in a breaker, you know.... That's the way I analyze tennis."

Which reminds me of a couple of trivial observations. The toweling off between points is now rampant. It naturally occurs when players change sides, but it is now a fixture between virtually every point. "Ridiculous," sniffs veteran tennis journalist Bud Collins, whose near-encyclopedic knowledge I had the pleasure to enjoy as we watched matches seated together.

And it seems every player must inspect every ball before selecting the perfect two before serving. I saw players do this even when they had just been given brand new balls right out of the can. What difference could there be? As a veteran chair umpire told me on the bus ride to the stadium, toweling off and ball inspection are slowing down the game and becoming obsessive behavior among the players.

Did I say obsessive behavior? Well, that brings us back to me, and my love for tennis.

Hang on. Before we carry this conversation further, I need to call the airline to see if I can get a ticket to next year's Indian Wells. Rehab can wait.