For kids: A board game with a peaceful resolution

Loading...

| Charlottesville, Va

Twenty-six fourth-graders walk into their classroom in Charlottesville, Va., to play the World Peace Game. When they enter, they know their own neighborhood, their school, and certain places in their hometown. By the time they walk out, they are on their way to becoming citizens of the world.

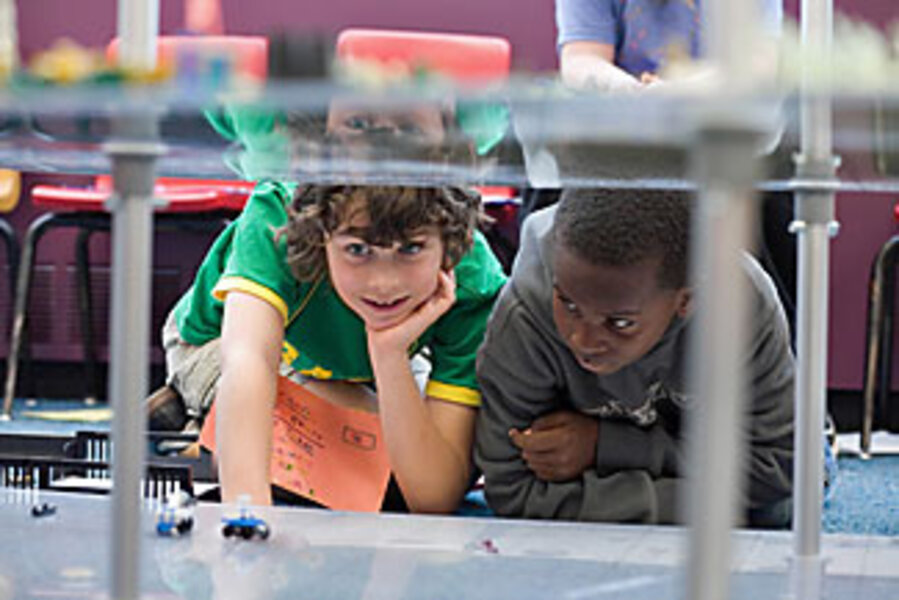

The game begins quietly, with the ring of a silver bell. Students take their seats around a 3-D structure – four layers of clear Plexiglas stacked four feet high to represent water, land, sky, and space. Each layer is divided into four parts and dotted with movable miniature ships, submarines, troops, planes, satellites, and energy reserves.

Teams of leaders from four nations – Verde, Tiger's Eye, Ushia, and Magnopolis – take their seats around the board. Their teacher, John Hunter, hands out crisis reports on the state of the world. Over the next few weeks, a group of 25 to 30 players will handle problems that include war, a shaky economy, natural disasters, poverty, and climate change.

Everyone has a role, such as prime minister, secretary of state, secretary of the treasury, secretary of defense. Some are members of the United Nations and the World Bank.

Throughout the game, some players draw cards that announce earthquakes, floods, tornadoes, and other random events. Cards drawn from another deck report financial losses and gains.

All four countries begin the game in conflict with one another. Mr. Hunter rings the bell again to begin negotiations, and teams go into noisy huddles to plan their moves.

Prime Minister Peters of Verde emerges from negotiations to announce a peace treaty between Verde and Magnopolis, the two most powerful countries. She also warns of a planned military strike on Tiger's Eye. UN Secretary-General Maupin suddenly decrees that Tiger's Eye will return land to Verde. Her team looks shocked. But before they have a chance to argue, someone draws a card that announces that the stock market has crashed.

Some leaders get along better than others, but everyone gets a say. From a distance, it looks like chaos, but the hard, important work of negotiation is always going on.

At first, players might wonder whether the fun will ever begin. Once they get the hang of it, though, they can't wait to get back. But how can you win when so many different things come at you from so many directions and all at once? There's really only one way – by working together for peace and prosperity for all.

This job is even harder than it sounds. You have to be flexible. To succeed you have to give up some things you really want so you can accomplish things that are important for everyone.

Throughout the game, reports keep coming in about spy satellites, weather disasters, and stock markets booming and crashing. Nothing ever stays still.

"You've got to take everything as it comes, prioritize everything, and get the stuff that you need done," says Willis Bocock, an eighth-grader who learned a lot about strategy from playing the World Peace Game. You have to "keep going down the list. It's pretty impossible to do everything at one time."

At the beginning of each session, Mr. Hunter, a teacher at Venable Elementary School and the inventor of the World Peace Game, reads a quote from "The Art of War," written by a Chinese general named Sun Tzu. The book contains various strategies including how to get out of war quickly – or better yet, avoid war altogether.

Throughout the game, leaders settle border disputes, trade goods, and grant or deny rights to native peoples. Sometimes they declare war.

"You can do anything in this game," says Mr. Hunter, "as long as you are prepared to accept the consequences."

His role is to ask tough questions and stir up trouble for the students to work their way out of.

Mr. Hunter invented the World Peace Game 30 years ago in Richmond, Va. In recent years, he has played the game with students at two schools in Charlottesville.

Only once has a group of students failed to win. The reason: They never found a way to work together.

To succeed, kids playing the game have to find new ways to solve complex problems.

"We were the smallest country and the poorest," says Willis, the eighth-grader, "so whenever a big country would gang up on us, we'd have to get other countries to help us."

This is similar to how things work in real-world diplomacy, which is an important point of the game.

"This is hard work," Mr. Hunter says to the leaders of Verde, Tiger's Eye, Ushia, and Magnopolis. "Adults have trouble doing it, too. You can do better."

Excited by the challenge, the young leaders get right back to work.

The World Peace Game models the real world in a way that allows kids to come up with their own solutions to problems of many kinds.

"You're prepared for everything that comes at you when you go out," says Willis. "Not just in the world, but if you have a personal conflict with just one or two other people, it helps with that, too."