The game is afoot: Why director sees Enola as more than Sherlock’s sister

Loading...

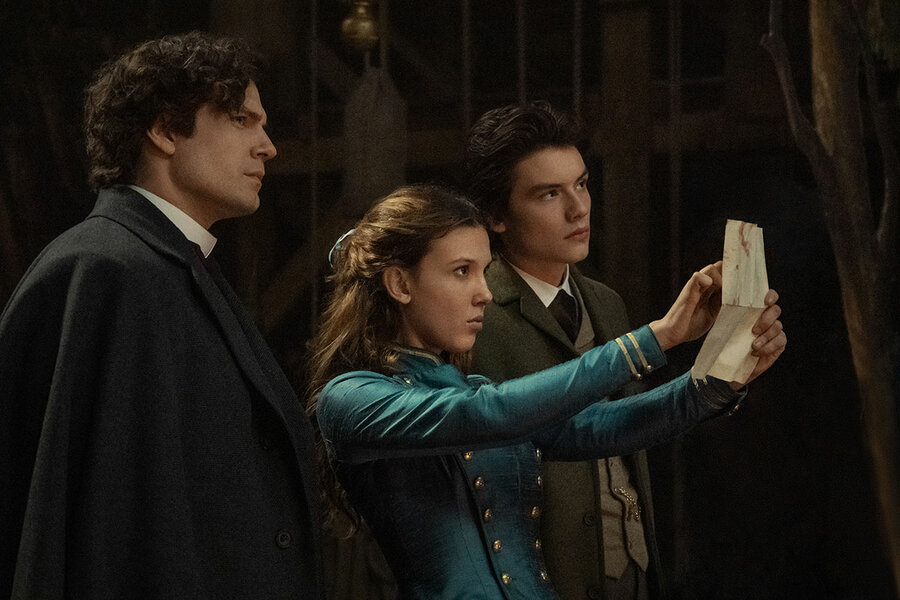

“Enola Holmes 2” begins with the titular character – a detective, like her brother Sherlock – running through Victorian-era London. Police are in hot pursuit. The game is, indeed, afoot. The sequel to Netflix’s 2020 hit finds Enola Holmes (Millie Bobby Brown) struggling to launch a detective agency. In a montage featuring Monty Python-style cut paper animation, the teen details how prospective clients dismiss her because she’s a girl. Besides, they’d rather hire her famous older sibling (played by Henry Cavill). Enola eventually finds a case: A girl who works at a match factory has gone missing. Director Harry Bradbeer (“Fleabag,” “Killing Eve”) again teamed with screenwriter Jack Thorne for a sequel based on the young adult novels by Nancy Springer. The Monitor recently interviewed, via Zoom, the Emmy-winning British director known for stories that feature compelling female protagonists. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

We’ve come a long way since the 1880s, and women have rights they didn’t have back then. Why do the themes of equality in the Enola Holmes films resonate with audiences today?

As you say, we’ve come a long way and yet we haven’t come very far. The progress we make can suddenly be dramatically reversed, as we’ve seen in some countries. Women are still clamoring to have their voices heard and to be given respect in their own right. So it’s everywhere. We see it in parts of the Middle East. ... You can’t stop making that argument. It still has to be made. There’s no room for complacency. We see, again, in another country at the moment, it’s only by uniting men and women together that change seems to happen.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onWhen he set out to make “Enola Holmes 2,” director Harry Bradbeer had several things in mind, including how to help his sleuthing main character work as well with others as she does alone.

Who came up with the storyline based around the real-life working conditions at a matchmaking factory in 1888, and how does that plot inform the movie’s themes?

We wanted to tell a story of going from “I” to “we.” The first film was about a girl learning to be able to stand on her own two feet and be a detective in her own right, to some extent beside her brother. So it was about finding individual power. The second film we [threw] her into the world of London with many different challenges. ... We wanted to find where to push it narrow to the point where she has to cooperate with others. She has to learn to work [in] a group.

And as we were working on that story, we were looking ... for a subject and a relevant event as we had in the first film, where it was the Great Reform Act. Jack thought of the Match Girls’ Strike of 1888. Because when you’re fighting, as the match girls did, the powers of authority and of capitalism and of big business, you can’t do it on your own. It has to be a group. And the idea of the very first female-led strike was just irresistible to us.

Enola’s love interest, the Viscount Tewkesbury, shows her how to dance in the ballroom. She shows him how to fight. How does the sequel explore how Enola and the viscount each subvert traditional gender roles?

We followed the truth of them because he, at the start, is a man standing on his own feet, actually forging his way as a real man in politics. What’s tricky for her is his strength and confidence at a point where, in her own life, she’s struggling – first of all, getting a job and then solving the mystery she’s given. So we reversed the roles to some extent, and then they meet in the middle. They still have things to learn from each other. He teaches her something soft. She teaches him something hard.

Prior to the first film, you expressed hope that stories after the pandemic would be less cynical and would value human relationships more. How do those values inform “Enola Holmes 2”?

I think we’re all basically [asking], “What’s my motivation?” It’s always you want to be loved. ... So that’s been universal in my work, and I think I probably would have done that with or without the pandemic. But I was struck at how much people related to the first film, particularly its emotional aspects, and how people cried at the end. I wanted to build on that by building more complex relationships between all the characters.

The most uncynical aspect of the second film is how the film ends with the way that Enola ... brought those [matchmaking girls] together. So the idea of uniting and forming a common cause, I think, was one of the most uncynical things I think I’ve ever put together.

“Enola Holmes 2” debuts on Netflix on Nov. 4. It is rated PG-13 for bloody images and some violence.