In Pictures: In Senegal, the kora ‘brings me closer to God’

Loading...

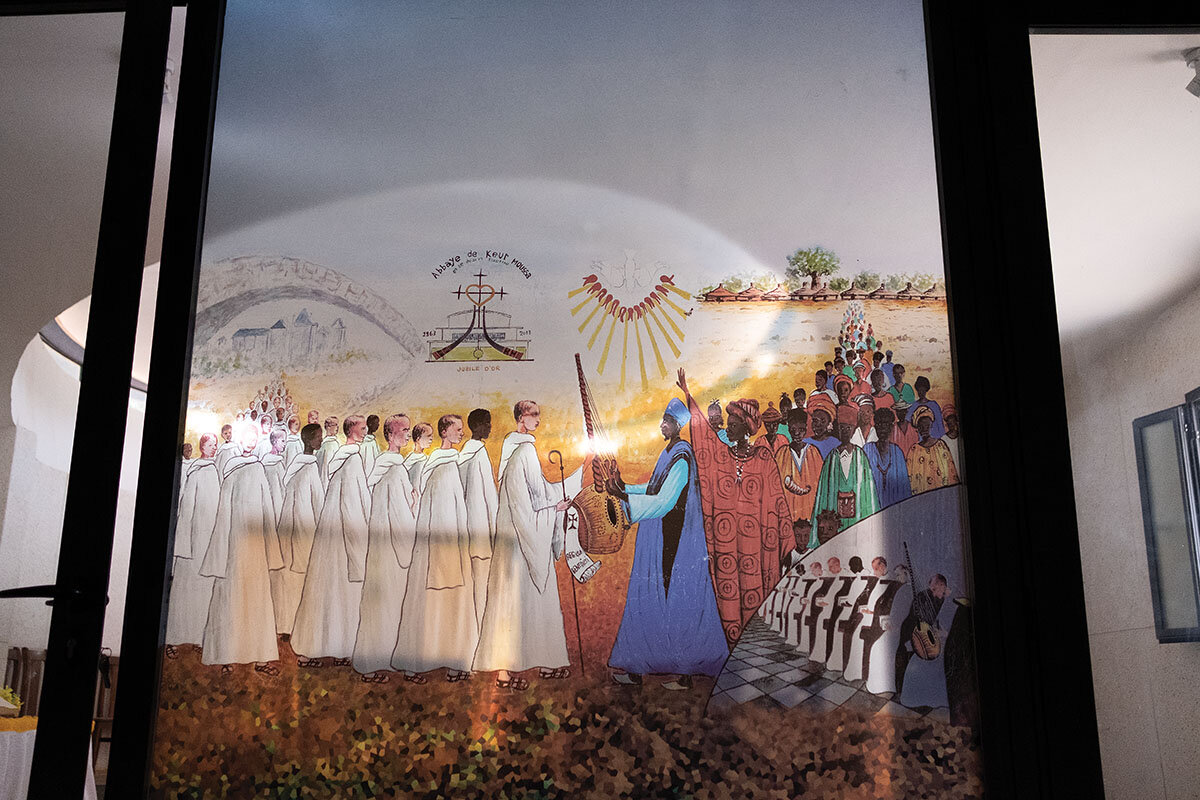

| Keur Moussa, Senegal

Morning sun filters into the monastery church as the melodic twang of two harplike instruments – known as koras – fills the air, combining with the voices of two dozen singing monks. The music rises up the white walls and out through the latticework near the roof – lyrical, looping melodies filled out by warm bass notes.

The kora has been used across centuries by everyone from West Africa’s pre-colonial singing historians to modern jazz and rock groups today.

But the kora was little known in Senegal outside of the minority Mandinka ethnic group before the monks of Keur Moussa Abbey started using it. In the 1960s, when the Roman Catholic Church was modernizing and just after Senegal had shaken off French colonial rule, the monks of Keur Moussa embraced the instrument, morphing their Gregorian chants into songlike prayers accompanied by the kora.

“It was work – it didn’t just happen,” says Brother Marie Firmin Wade, who builds koras. “That’s what has created all the liturgical richness of Keur Moussa. Because Keur Moussa has taken a bit from everywhere.”

Congregant Hélène Ngom, walking out of a recent Sunday mass, says, “It’s an instrument that when you listen to it, it takes you. When I listen to the kora, I rise, divinely. It brings me closer to God.”