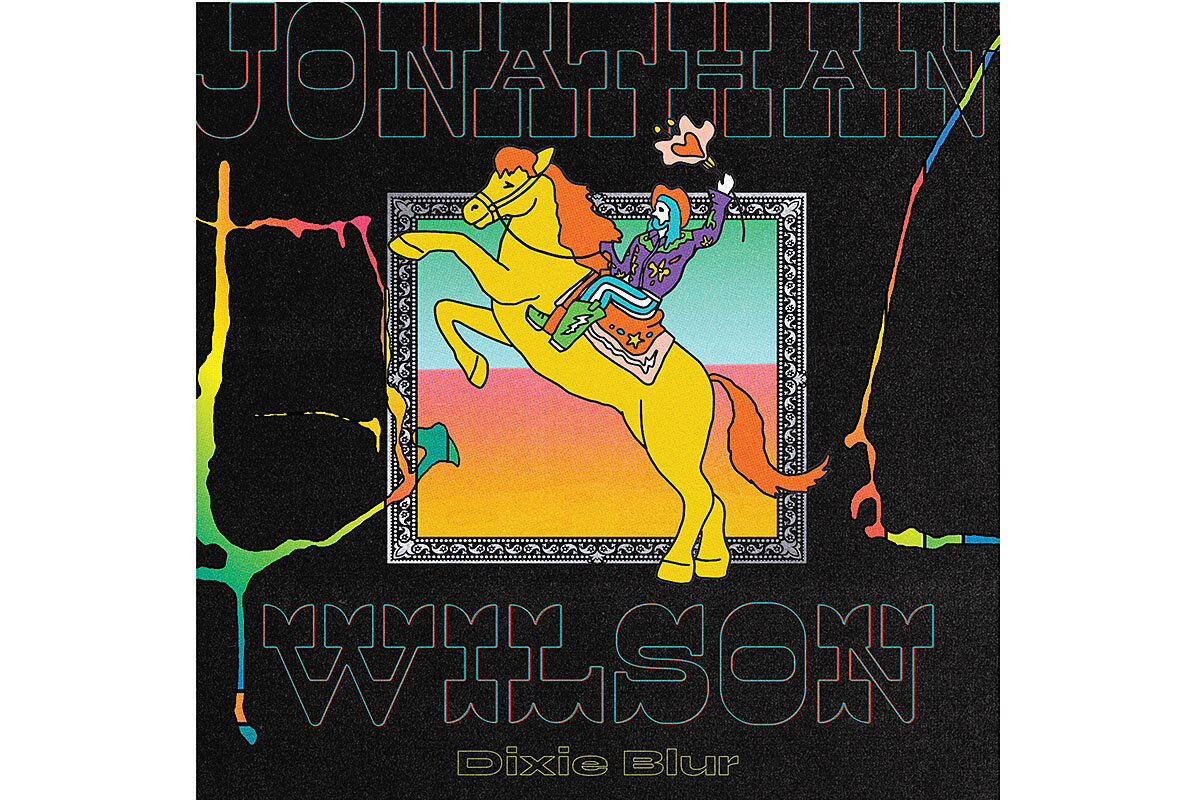

Drawing on his roots, a rock guitarist finds a new rhythm in Nashville

Loading...

Until recently, songwriter Jonathan Wilson recorded his solo albums the way he handcrafts his own guitars as a luthier. An auteur and multi-instrumentalist who’s as comfortable behind a studio mixing console as he is behind a drum kit, he would painstakingly chisel and lathe each layer until the final album gleamed under its lacquered varnish.

But after spending nine months recording the 2018 album “Rare Birds” – a “maximalist” production with 1980s touchstones such as Fleetwood Mac’s “Tango in the Night” – Mr. Wilson yearned “just to go somewhere, get completely out of my zone, and to do something completely different.”

His new album, “Dixie Blur,” is, in every way, the antithesis of its lush predecessor. It’s a rustic Americana album recorded entirely live in just six days with a group of strangers in a completely foreign environment. He’s left splinters in the record – adopting a pared-down, roots-driven path to his latest sound.

Why We Wrote This

Taking risks artistically can lead to new ways of thinking. When Jonathan Wilson, a detail-oriented musician, loosened his control over the final product, he found a new approach to expressing himself.

“Folks might look to me for like a psychedelic, rock-y, California song vibe or something like that. I wouldn’t want to get into the conundrum of trying to constantly be that guy,” says Mr. Wilson, also an in-demand session player, co-writer, and producer for the likes of Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters, Lana Del Rey, and Father John Misty. “It bums me out when I hear artists that make the same song again.”

Credit Americana icon Steve Earle for inspiring the concept for “Dixie Blur” during a radio program last year. “We were doing this NPR show and he was like, ‘Maybe you should go to Nashville,’” recalls Mr. Wilson, who is based in Los Angeles.

After that, he called up his friend Patrick Sansone from the band Wilco to co-produce the album and also act as a guide to the best studio and session musicians in Tennessee.

It seemed to Mr. Wilson that the songs he’d been working on could work with instruments such as fiddles and pedal steel guitar. After composing “Rare Birds” on a Steinway piano, Mr. Wilson returned to writing on an acoustic guitar for the latest album. It simplifies things harmonically, he says. Just strumming a G chord suggested a more bluegrass and country feel. Of late, he’d also begun to reflect on his own Southern roots in lyrics such as those on the autobiographical new “69 Corvette.”

Mr. Wilson, who has a night job as one of the principal guitarists and vocalists in Mr. Waters’ band, wrote the song during a 157-date world tour with the former Pink Floyd songwriter. The song’s refrain about missing home emerged during a several-day layover in “Poland or something,” he says, expressing the disorientation of a touring musician who’s crossed more time zones than a satellite.

The artist recalls “just walking around the city by myself, going to vintage rock and clothing stores for the fifth or the 18th time.” He returned to his fancy hotel, picked up his guitar, and thought to himself, “‘Wow, this is a weird place to be from the place that I started,’ which was a little tiny town where there was nothing going on.”

Before he became a teen guitar hero in Spindale, North Carolina, Mr. Wilson played in the Baptist church where his grandfather was a preacher and his grandmother was choir director. It gave the songwriter an appreciation for the relationship between music and spirituality: “When I would sit and compose some of my early stuff, I would try to join up with some sort of meditative ... spiritual element.” Nowadays, the tricky part of songwriting, he says, is finding mental space because he’s “tethered to the phone and the ’gram.”

“It can be hard, but I usually get to a place where I’ve got my piano and I can sit while the rest of the planet is in bed,” he says. “That’s the quiet time. And so that’s when the stuff comes.”

The Nashville recording sessions for “Dixie Blur” at Cowboy Jack Clement’s legendary Sound Emporium Studios offered a different sort of communion. Mr. Wilson felt instant musical kinship with session luminaries including Dennis Crouch (bass), Russ Pahl (pedal steel guitar), and Mark O’Connor (fiddle). Beneath the dusky lights in Studio A, where wooden awnings cast shadows over the parquet floors and Persian rugs, they recorded songs ranging from the furious gallop of “El Camino Real” to the slow lament of “Riding the Blinds.” Mr. Wilson thrived on the feedback of seasoned players who said, “Don’t bore us; get to the chorus.” The process allowed for spontaneity to change the tempo, the key, and the feel of the melodies – sometimes at the suggestion of the musicians.

“If the album would have been done here in Hollywood, those guys would have been asking for publishing [rights],” he jokes.

Next, the songwriter has a solo tour for “Dixie Blur,” which, he says, has the feel of a classic album.

“This definitely was my first time to let go and trust in the process to this extent,” says Mr. Wilson, who explains his habit has been to endlessly tweak recordings to perfect them. “It’s going to be a lot more powerful to ... actually hear that sort of a purity of a document that was done in a certain time with some soft songs.”