‘Asteroid City’: Stars, galaxies, and the meaning of life

Loading...

When an artist is described as an “acquired taste,” the implication is that the taste is worth acquiring. Wes Anderson, whose new movie is “Asteroid City,” is a writer-director I have long been on the fence about. He is a true original, and yet what he originates can often seem confoundingly peculiar. He’s the cult director par excellence for obsessive-compulsive cineastes.

I don’t know that “Asteroid City,” co-written with Roman Coppola, represents a vast stylistic departure for him. And yet, more so than with some of his recent films, like “The French Dispatch,” or even such earlier celebrated works as “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” not only did I marvel at its color-coordinated craftsmanship, but I also found parts of it to be emotionally moving – a rarity in the Anderson canon.

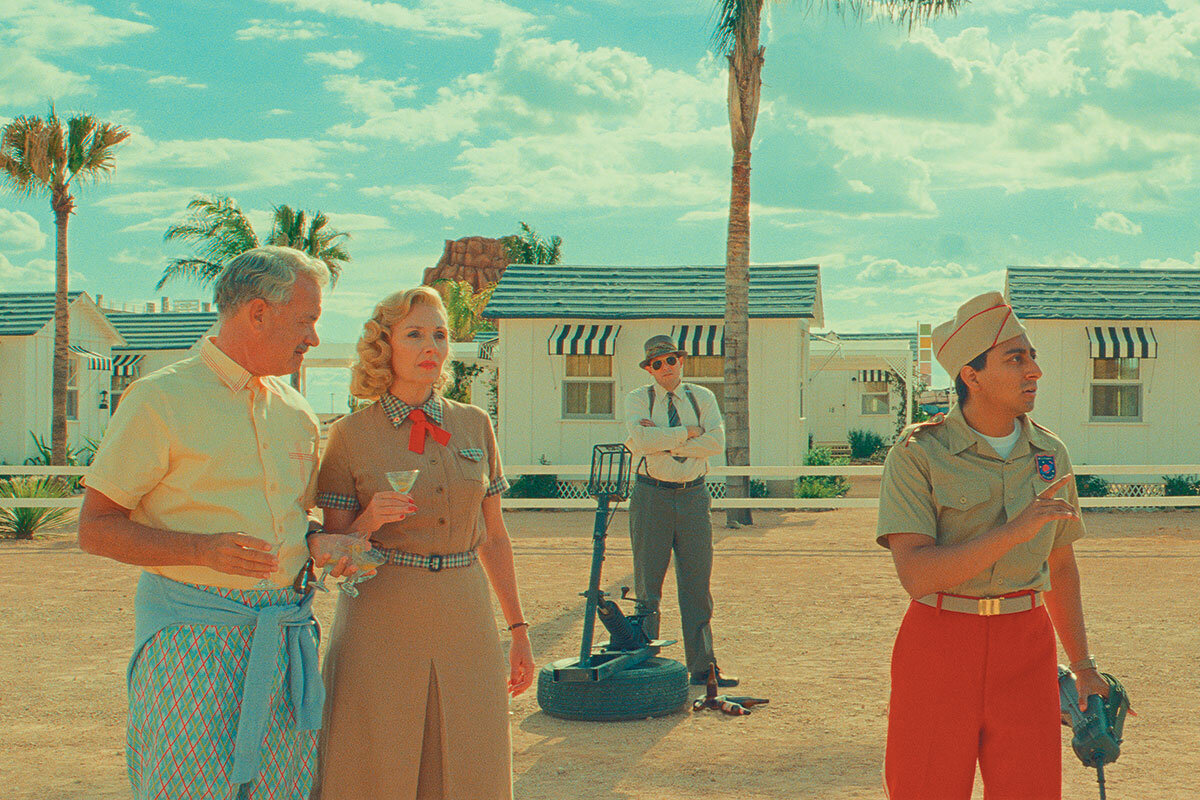

The bulk of the movie takes place in 1955 in the remote fictional desert town of Asteroid City, the site of the annual Junior Stargazers convention honoring a bunch of teenage brainiacs. (It’s the dawn of the Cold War, and A-bomb tests occasionally mushroom in the far distance.) Accompanied by their parents, these hypernerdy whiz kids are rousingly welcomed by the event’s emcee, a five-star general played impeccably by Jeffrey Wright, whose rigorous diction is the loony height of military officialese. No doubt he sees these kids as future bombmakers for a more powerful America.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe latest movie from Wes Anderson features the ingenuity and absurdity he’s known for. But more so than his other recent films, this one is fused with an undercurrent of emotion.

To the extent that this film’s glutted-with-stars cast has a leading protagonist, it’s Augie Steenbeck (Jason Schwartzman), a war photographer accompanied by his three young daughters, all named after constellations, and his honoree son, Woodrow (Jake Ryan). It is revealed early on that, unbeknownst to the kids, their mother, whose ashes Augie is toting, died three weeks earlier. Until now, he has been too depressed to tell them, much to the consternation of his father-in-law (Tom Hanks), who grumpily arrives on the scene to assist when the family car breaks down.

Augie’s counterpart is Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johansson), a mysterioso Hollywood star encamped in the desert across the way from him, whose supersmart daughter Dinah (Grace Edwards) warms to Woodrow. Their growing geek rapport is sweet: Peering through a telescope, Dinah opens up to him by saying, “Sometimes I feel more at home outside the Earth’s atmosphere.” For his part, Woodrow, a born skeptic, wonders if maybe there is a “meaning of life.”

Anderson frames this central story, which includes a loopy alien visitation, as a television play-within-a-film conceit, complete with notated acts and scenes. This is both confusing and unnecessary. But the main drama, photographed in a sun-bleached pastel palette, has a marvelous look – dazzling yet spectral – and the players who populate it have an uncanny harmony. (The cast, too numerous to fully cite, also includes Tilda Swinton, Liev Schreiber, Hope Davis, Matt Dillon, and, in the black-and-white framing section, Ed Norton, Adrien Brody, Bryan Cranston, and Margot Robbie.)

The performers frequently deliver their dialogue with a clipped cadence that adds to the overall heightened theatricality, as does the toylike production design – with its 1950s station wagons, diners, and gas stations. At times the movie resembles a live-action rendering of an animated film. (Anderson has in fact made several animated movies, the best of which is “Fantastic Mr. Fox.”)

It could be argued that these people are, in essence, glorified cartoon characters, but unlike much of Anderson’s earlier work, some human empathy comes through anyway. The grief that Augie feels for his wife is real. The world-weariness of Midge carries a lived-in melancholy. The brainy conviviality of the Junior Stargazers is touching – they relish the opportunity to be around kids as smart as they are.

What accounts for Anderson’s (relative) change of heart? I think it’s because, for all his caustic absurdism, he has found himself open to the immensity of the cosmos in a way that he can’t entirely make fun of. Like Woodrow, he is looking out for the meaning of life.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “Asteroid City” starts rolling out in theaters on June 16. The film is rated PG-13 for brief graphic nudity, smoking, and some suggestive material.