In ‘Till,’ the power of a mother’s love

Loading...

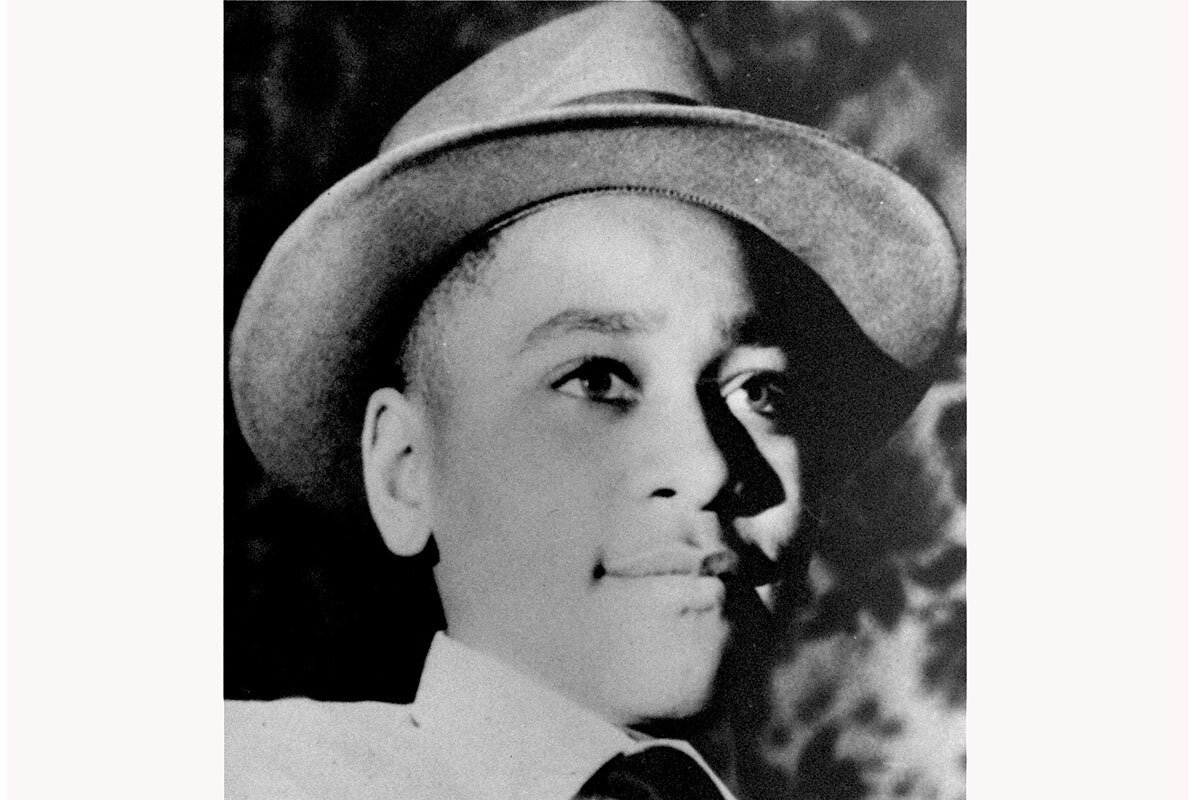

A single word captures the essence of “adding insult to injury” – indignity. Humiliation, hatred, hurt – these three words are part of the indignity that encapsulates the brutal murder of Emmett Till. The legacy of Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, was her commitment to cut through that indignity, even if she had to employ the ugly truth and tragedy as a weapon.

I was reluctant to engage “Till” at first. I branded the movie and presentations of its ilk as the “trauma industrial complex” – a painful and perhaps needless rehashing of Black trauma. A statement from “Till” director Chinonye Chukwu changed my mind:

The crux of this story is not about the traumatic, physical violence inflicted upon Emmett – which is why I refused to depict such brutality in the film – but it is about Mamie’s remarkable journey in the aftermath. She is grounded by the love for her child, for at its core, TILL is a love story. Amidst the inherent pain and heartbreak, it was critical for me to ground their affection throughout the film. The cinematic language and tone of TILL was deeply rooted in the balance between loss in the absence of love; the inconsolable grief in the absence of joy; and the embrace of Black life alongside the heart wrenching loss of a child.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onLove sometimes comes in the form of openness – even when that means revealing a brutal truth. Our commentator found that depth of love in the movie “Till.”

“Till” does a masterful job in its display of indignity, from its depiction of the Jim Crow South to the deliberate injustices of law enforcement, even the respectability politics present among Black people. Danielle Deadwyler’s Mamie is at her best when she dealt with a harsh reality – America needed to see the literal brutality of racism, leading to her decision to have an open casket at his funeral.

It is difficult to review a movie like “Till” without reviewing society altogether. Jalyn Hall, the young man who plays Emmett, could have just as easily starred in a movie about Tamir Rice, the Ohio 12-year-old who was killed by police. I learned about Emmett as a preteen, and though he might have been a peer of mine, I would not have been able to grasp the fullness of such a tragedy.

And I wasn’t yet a father when Tamir was killed, but I agonized over the senselessness of his death and those like it.

I write this now as a father of two sons, and Emmett’s murder adds a more intimate burden, more gravitas, comparable to the pain I feel as a Black man. This quote from former President Barack Obama echoes solemnly: “If I had a son, he’d look like Trayvon.”

This is where the indignity is thickest. For too long, Black people in America have engaged in a system that can kill your children and make a mockery of you, your family, and your people.

That angst can turn an innocent backdrop into a cruel ballad of perseverance. “Just smile,” reads a toothpaste ad as the camera pans away in a transition from precarious Chicago to the perilous Mississippi Delta. Grin and bear it.

The only solace is found in the community. “Till” juxtaposes the horrors of racism with the shared sense of family and fears that kindred spirits face. There are the Chicagoans who rally around Mamie when they hear of Emmett’s kidnapping. There are the Black advocacy and activist organizations across the country that do their best in the face of adversity.

The point of “Till,” of course, is not harm. It is history and honor, as Ms. Chukwu reminds us:

Mamie’s untold story is one of resilience and courage in the face of adversity and unspeakable devastation. For me, the opportunity to focus the film on Mamie, a multi-faceted Black woman, and peel back the layers on this particular chapter in her life, was a tall order I accepted with deep respect and responsibility. On the daily, Mamie combatted racism, sexism, and misogyny, which was exponentially heightened in the wake of Emmett’s murder. Mamie did not cower. Instead, she evolved into a warrior for justice who helped me to understand and shape my own similar journey in activism. And as a filmmaker, showing Mamie in all her complex humanity was of utmost importance.

People familiar with the Till tragedy might also be interested in the story of Medgar Evers. The Till case was one of the slain civil rights activist’s first assignments, and the movie provides introspection between two mothers of the movement: Mamie and widow Myrlie Evers.

Till – what a heavy surname. The word, by definition, speaks to farm labor, working tirelessly in pursuit of harvest. It speaks perfectly to Black people’s quest for justice and equity. The word “till” is also a statement of time – a period of longing, or as the end of the first verse of the Black national anthem declares: Let us march on ’til victory is won.

“Till” is rated PG-13 for thematic content involving racism, strong disturbing images, and racial slurs.