In ‘The Mauritanian,’ Hollywood takes on Guantánamo. Can it do it justice?

Loading...

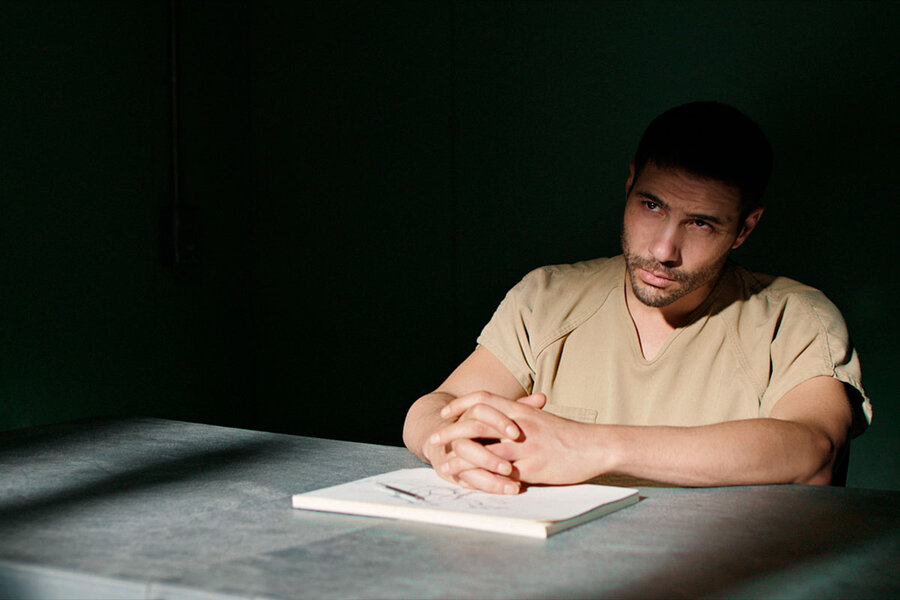

In November 2001, Mohamedou Ould Slahi was approached by the local police in his native Mauritania and told that the “Americans want to talk to you.” Suspected of high-level involvement with the 9/11 hijackers, he was detained and eventually imprisoned without charges in Guantánamo Bay by the U.S. government. The intermittently compelling “The Mauritanian,” which draws on Slahi’s bestselling 2015 memoir “Guantánamo Diary,” and stars Tahar Rahim as Slahi and Jodie Foster as his chief defense attorney, Nancy Hollander, dramatizes the 14-year ordeal leading to his release.

Director Kevin Macdonald and his screenwriters, Rory Haines, Sohrab Noshirvani, and M.B. Traven, offer up this volatile material, including torture scenes, in the straightforward manner of a legal procedural. Presumably the filmmakers decided that the injustices could speak for themselves without any pumped up filmic pyrotechnics.

What pulls the movie out of its stylistic complacency is Rahim’s performance as Slahi. Best known for his role as the Muslim mobster in the prison drama “A Prophet,” Rahim holds the screen even when he is seemingly doing nothing at all. His presence is like a force field. Rahim’s cagey underplaying clashes with Foster’s hypertense emoting in many of their scenes together. And yet these scenes mostly work anyway because the dynamic between them is so clear-cut. Hollander is furiously driven to restore Slahi’s civil liberties. Professing his innocence, Slahi nevertheless believes he is already condemned. “Whatever I say,” he tells her, “it doesn’t matter.”

Why We Wrote This

After 9/11, extreme U.S. interrogation techniques were scrutinized. As a new movie, “The Mauritanian,” revisits that time, film critic Peter Rainer wonders how well equipped Hollywood is to dramatize incendiary political subjects.

Hollander sues the U.S. government on Slahi’s behalf. Under the Freedom of Information Act, she requests a warehouse full of files pertaining to his case (most of which turn out to be redacted). But, to the film’s credit, she is not highlighted as the great liberator. Hollander and her assistant Teri Duncan (Shailene Woodley), who initially doubts Slahi’s innocence, are ultimately subordinate to his saga.

In some ways, the most compelling legal figure in “The Mauritanian” is Hollander’s adversary, Lt. Col. Stuart Couch, the Southern military prosecutor assigned to the case and who is powerfully played by Benedict Cumberbatch. (And yes, his Southern accent is just fine.) Couch’s good friend died in the 9/11 attacks and he relishes the prospect of trying Slahi. But as the evidence mounts that Slahi’s “confession” was obtained by torture, Couch, who has a deeply held Christian faith, refuses to participate in the proceedings in 2004, ending the prosecution and making him a pariah among his colleagues. Even so, it would take until 2016 for Slahi to be released from Guantánamo, which remains open.

In the film’s end credits we see footage of the real Slahi seemingly enjoying his freedom, listening happily to a Bob Dylan recording. We are also shown clips of the other main protagonists. For me, this common docudrama practice unfairly undercuts the authenticity that preceded it – reminding us we’ve been watching a bunch of impersonators.

In the case of “The Mauritanian,” this choice also brought up a larger question for me: Should Hollywood dramatize incendiary political subjects of recent memory at all? It’s the same question I had when 9/11 movies like “United 93” (2006) came out. It’s how I felt about “Zero Dark Thirty” (2012), which, unlike “The Mauritanian,” didn’t even take much of a moral position on the torture we were witnessing. (Tellingly, I had no such qualms while watching Errol Morris’ 2008 Abu Ghraib documentary, “Standard Operating Procedure,” perhaps because what we were witnessing wasn’t “real,” it was real.)

It’s not simply that it’s “too soon” for such movies. That’s highly debatable. More to the point is that the stark reality of these explosive events as we live through them – in the news, in real time, on TV and through investigative documentaries – potentially outflanks any attempt to dramatize them using embellished scenarios and famous actors.

I raise this issue also because it’s only a matter of time before Hollywood inundates us with pandemic-themed dramas. I’m not saying such headline-grabbing movies should not exist. But in these times especially, we need to ask more of Hollywood. An efficient procedural like “The Mauritanian” has its place, but what we need now – what we require – is the singular power that only art can provide.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “The Mauritanian” opens in theaters on Feb. 12 and is expected on streaming platforms in early March.