Movies that capture the moon’s wonder

Loading...

I remember watching the Apollo 11 moon landing on television as a teenager and thinking, “This is the most transcendent film I’ve ever seen.” I had, of course, watched many a moon movie over the years, but witnessing the real deal was a vastly different experience.

Not that, prior to Apollo 11, I imagined the lunar surface was made of green cheese. But the moon, up until that time, occupied an especially pulpy place in the cinematic firmament. It was a genre for which I retained an abiding affection, for even sci-fi schlock is capable of conveying a sense of wonder.

This wonderment shows up from the very beginnings, in 1902, with the French magician and toymaker Georges Méliès’ charming semi-animated short “A Trip to the Moon,” with its iconic shot of a rocket landing splat in the eye of the unamused Man in the Moon.

Why We Wrote This

Ahead of the 50th anniversary of the first moon walk, our film critic surveys lunar offerings that have grabbed the public imagination. How have our perceptions been influenced by what we watch?

Many of the moon’s inhabitants turn out to be prancing pixies who, when clobbered by the arriving astronauts, vanish in a puff of smoke. As moon people in the movies go, these creatures are among my favorites, although a close runner-up would be the cat women in unitards in 1953’s “Cat-Women of the Moon.” But I digress.

The first moon movie with any kind of scientific credence was Fritz Lang’s 1929 “Woman in the Moon,” which had the input of German scientists and featured such innovations as a multistage rocket, cinema’s first launch countdown, and reclining astronauts restrained by foot straps in zero gravity. Of course, the film was also replete with scientific howlers, including the breathable atmosphere on the far side of the moon. Who knew?

Until the Apollo 11 mission, moon movies were primarily the province of the frazzled reaches of sci fi, with their stiff, stalwart performers and chintzy production designs and dunderheaded plots. Some of them, though, such as the 1950 Technicolor “Destination Moon,” aren’t half bad. (It won an Oscar for special effects.) The film’s premise is that private industrialists finance a spacecraft to the moon. Doesn’t seem so far-fetched now. Another favorite is 1964’s “First Men in the Moon,” which is based on an H.G. Wells novel and features giant caterpillars and insectoids.

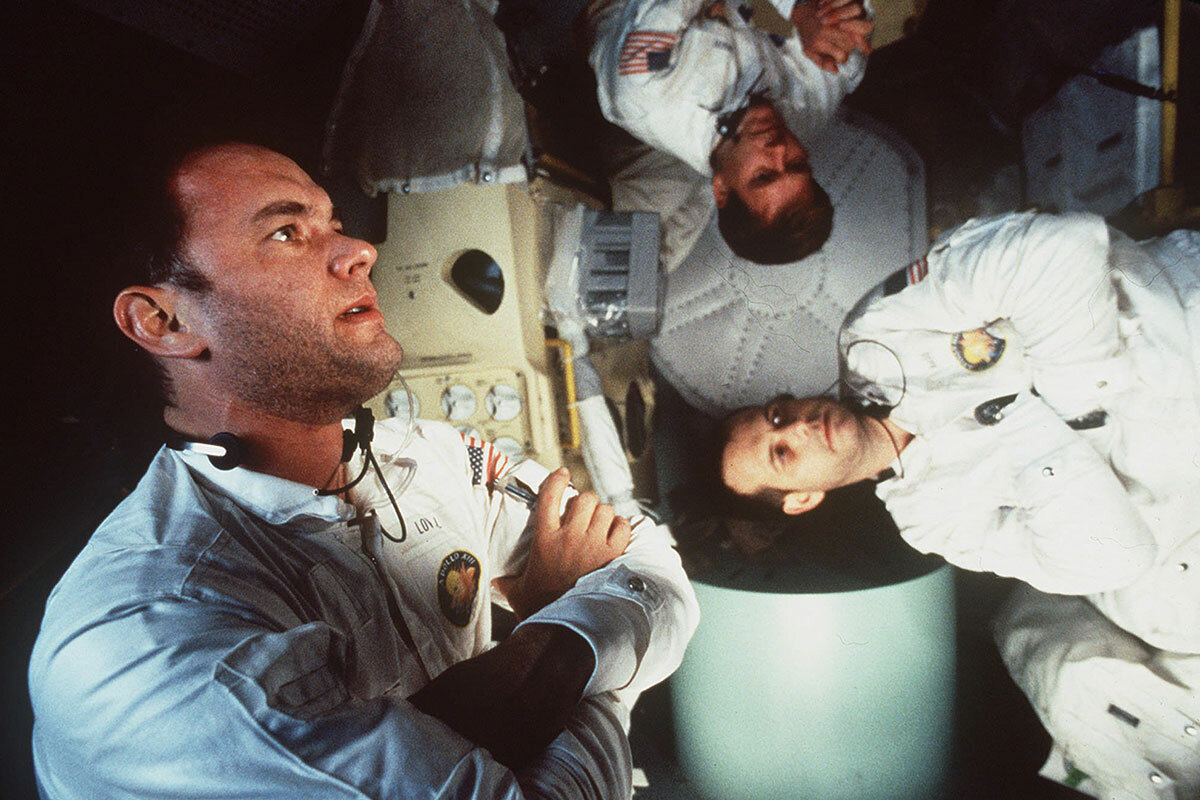

The schlock mostly disappears from moon movies after Apollo 11, and this makes sense. Neil Armstrong, to my knowledge, never encountered any insectoids. Also, special effects technology had vastly improved. On the ascendant were either documentaries that often relied heavily on archival NASA footage or dramas, such as Ron Howard’s 1995 “Apollo 13” and Damien Chazelle’s 2018 “First Man,” featuring more “personal” depictions.

The best of the documentaries are 1989’s “For All Mankind,” which blended the various moon missions into a single seemingly seamless flight; 2007’s “In the Shadow of the Moon,” which showcased remastered NASA footage along with interviews conducted with all the surviving crew members from every single Apollo mission (except for Armstrong); and, most recently, “Apollo 11,” which featured, without narration or contemporary interviews and utilizing newfound NASA footage, the entire mission from pre-liftoff to post-recovery.

The reliance on humanizing the astronauts in, for example, “Apollo 13” was an attempt to provide what the documentaries didn’t: a theatrical framework for more personalized stories, employing actors, such as Tom Hanks, who were more emotionally expressive than their real-life counterparts. Similarly, “First Man” tried to demythologize Armstrong, depicting him as a man of deep feeling, however submerged. But, as Ryan Gosling played him, he was a riddle who remained so.

And yet, in all these movies, including even the schlock, a sense of awe still prevails. Especially the documentaries and post-Apollo 11 movies offer up an unapologetic vision of bravery and an unfettered idealism intended to unite the world. The title of “For All Mankind” is meant to be taken literally.

Lowering Armstrong to the level of an ordinary man in “First Man” was a losing battle. The beauty of heroism will always reside in the extraordinary.