Orson Welles would likely approve of making-of doc 'They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead'

Loading...

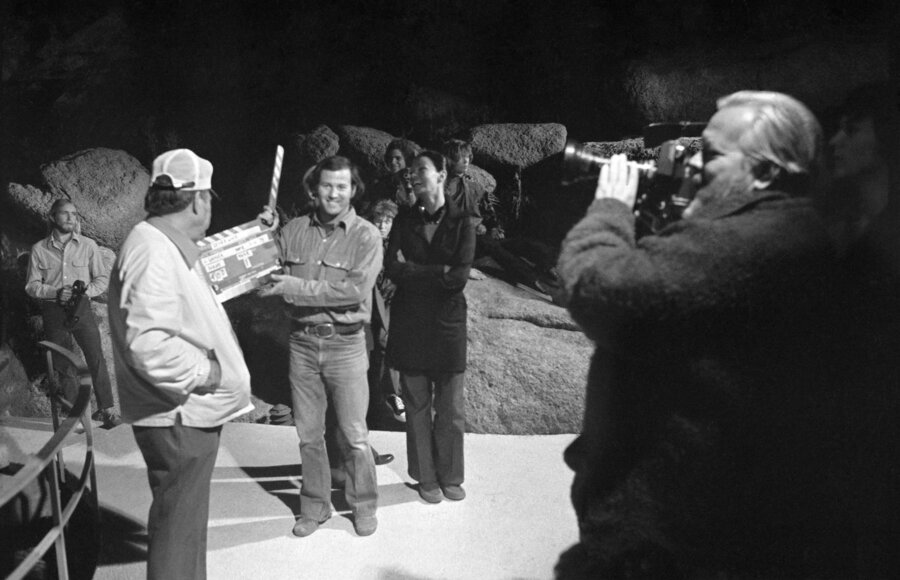

From the indefatigable filmmaker Morgan Neville, who earlier this year came out with the marvelous Fred Rogers documentary "Won’t You Be My Neighbor?," comes "They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead," which chronicles the making of Orson Welles’s “final” film, "The Other Side of the Wind." "Wind" was shot between 1970 and 1976 and was only partially edited. It was beset by legal woes and held in French vaults and labs for almost 40 years. Both Neville’s film and “The Other Side of the Wind” are being released simultaneously in theaters and on Netflix. I would advise seeing Welles’s film first. It’s more rewarding and less confusing that way.

The title to Neville’s film comes from a supposed pronouncement from Welles about his legacy, and surely the bitterness and rue in that statement was pure Welles. He felt betrayed by Hollywood, which, apart from “Citizen Kane” – a movie he called “the curse of my life” – was never a hospitable habitat for his genius. Neville’s film, which draws on interviews with surviving crew and actors as well as behind-the-scenes footage, explores the making of “The Other Side of the Wind” (less so the mechanics of its restoration) but focuses equally on Welles’s mythology, some of it self-made, all of it enthralling. How much of his woes – the botched, unfinished projects, the financial oppressions – were self-inflicted is a matter of debate and perhaps more suitably addressed to a psychiatrist than a film critic. But I have always been partial to the belief that, for all of Welles’s piteous bluster, he was far more sinned against than sinning. One of the saddest sequences in movies is the clip in the documentary from the 1975 AFI Life Achievement Award, when Welles, basking in his standing ovation, slyly, imploringly, all but begs Hollywood for money to complete “The Other Side of the Wind.” Not a dime, we are informed, came through.

Neville includes clips of Welles talking about “The Other Side of the Wind” years before he started production. He intended the movie as his Hollywood comeback film. In several of the clips, shot in the late 1960s, he regales a group of journalists by describing the film as unlike anything ever before seen – a combination of documentary, improvisation, movies within movies, and so on. It’s a tantalizing performance, and he caps it off by saying that maybe the picture itself will end up being “just talking about a picture.” It’s a classic piece of Wellesian reverse-field prestidigitation, but it also lends Neville’s documentary a spooky aura it might not otherwise possess. His film isn’t just a companion piece to “The Other Side of the Wind.” As it turns out, bearing Welles’s words in mind, it becomes almost a meta version of Welles’s movie. I would like to think that the great magician himself would have approved. Grade: A- (This movie is not rated.)