‘I Called Him Morgan’ embraces ambiguousness of story

Loading...

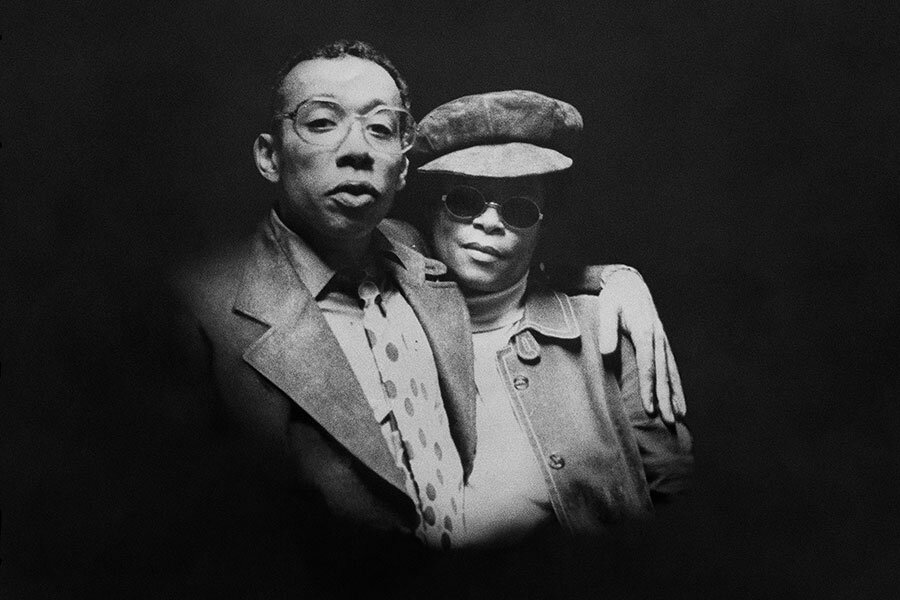

Trumpeter and composer Lee Morgan, the subject of Swedish documentarian Kasper Collin’s remarkable new film, “I Called Him Morgan,” was one of the most gifted jazz musicians of the second half of the 20th century. He joined the Dizzy Gillespie Big Band in 1956 when he was just 18, toured with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers at the end of that decade, and recorded 25 albums with Blue Note Records. All this was before his death in 1972, at 33, from a gunshot wound inflicted by his common-law wife, Helen Morgan (nee More).

Collin’s approach to this incendiary material is both blatant and oblique – a bit like Lee’s playing itself. Thankfully, we hear quite a bit of that playing in the film. Early on, Collin offers up a video clip of Lee soloing in an ensemble, and the effect is instantly bracing. He was a master of hard-bop jazz, and his sound was commanding, insinuating, and mellifluous all at once. He was a swinger-classicist: His inner clock had a furious, rhythmic propulsion.

The “I” in the film’s title belongs to Helen, on whom Collin expends almost as much screen time as he devotes to Lee. He relies heavily not only on testimony from Lee’s great, surviving jazz collaborators – including Wayne Shorter, Billy Harper, Bennie Maupin, and Larry Ridley – but also on a prime piece of happenstance.

In 1992, Larry Reni Thomas, an instructor for adult education classes in Wilmington, N.C., who also served as a local radio jazz DJ, discovered that one of his older students was Helen, who had been living quietly in the neighborhood for decades. Knowing something but not much about the circumstances of Lee’s death, he asked to interview her. Eight years later, she consented, and the results of that interview, recorded on hissy audiocassette, are played out periodically throughout the film. (She died less than a month after the interview.)

The fascination of Lee and Helen’s entwined story lies not only in how it encompasses an entire era of jazz, it’s also a full-scale mutual tragedy, for Helen was the person who rescued Lee from heroin addiction and saved his career. She grew up on a farm in North Carolina; gave birth successively to two children, who were raised by their grandparents, starting when she was 13; and later made her way to New York City, where she worked as a phone operator and fell in with the bohemian crowd, cooking up elaborate meals in her apartment that were legendary. (“I looked out for me,” she says on the audiotape. “I was sharp.”) By the time she met Lee, who was almost 15 years her junior, his addictions had spun him out of control. He would show up for gigs in slippers because he had hocked his shoes. He had no winter coat. A fellow musician spotted him in the subway and mistook him for a homeless person.

Helen became a kind of combination muse, mother, wife, and manager. After two years of rehab, Lee was back on the jazz scene, playing more forcefully than ever. (Collin doesn’t skimp on clips.) But he began seeing another woman, Judith Johnson, who is interviewed in the film. (She affectionately remembers how she called Lee “Howdy Doody” because of his big ears.) Helen threatened to leave him and move to Chicago.

One night, during a major snowstorm, Helen walked in on Lee during a gig at the popular jazz club Slug’s Saloon. After he ejected her, she returned and, in a sudden, blind rage, shot him with the same pistol he had once given her for self-protection. It took the ambulance an hour to arrive in the storm, too late to save him. After serving some prison time, Helen decamped to North Carolina, where, she says, she “found salvation in the church.”

Helen was Lee’s savior and executioner, but most of his friends feel that it was the savior part that ultimately held sway. Several of the musicians talk about how they wanted to hate her and yet, upon seeing her again after the murder, they remembered how devoted she was to Lee and his great gifts. In a way, she remained so for the rest of her life.

It’s a tremendously complex psychological landscape, and Collin doesn’t attempt to pin everything down and assign meanings to what is necessarily ambiguous. This is the second documentary he has made about tragic jazz artists who died young – the first was “My Name Is Albert Ayler” – and he clearly has an abiding fascination with them. But what draws him most of all is the music, and that’s as it should be. Grade: A- (This movie is not rated.)