'Winter Sleep' is a magnificent film that recalls Chekhov and Eugene O'Neill

Loading...

“Winter Sleep,” winner of last year’s Palme d’Or in Cannes, runs almost 3-1/2 hours. These will be some of the best three-plus hours you will spend at any movie this year. I’ve seen movies half that length that felt twice as long.

So many films are mistakenly called “Chekhovian” that it’s a real pleasure to celebrate one that is. (It’s actually loosely adapted from two Chekhov stories.) Nuri Bilge Ceylan, the director and co-screenwriter, with his wife, Ebru Ceylan, has a voluminous comprehension of the frailties of the human condition as they play out within a seemingly small compass. (So did Chekhov.) The film is set in the remote steppes of Cappadocia in central Turkey, a landscape thick with wild horses and caves and homes jutting from mountainous crags.

One such abode, the Othello Hotel, is run by the gray-bearded Aydin (Haluk Bilginer), a former actor of some renown who has retreated to the steppes with his young wife, Nihal (Melisa Sözen), to lord it over the countryside as a landlord and write a cranky weekly column for the local gazette. (Both actors are peerless.) “My kingdom may be small but at least I’m king there,” he says, with his usual humility. Aydin has the expansiveness of a man of privilege, and does not hesitate to pull rank. He disdains his wife’s attempts to raise charitable funds for a village school. For Nihal, this work is more than a pastime; it’s her way of breaking out of the confines of a bad marriage. Sensing this, Aydin bullies her.

His bullying is almost entirely verbal. He has an actor’s faith in the power of the spoken word, and he is confrontational not only with Nihal but with just about everybody else, including his embittered, divorced sister, Necla (Demet Akbag), who is not so miserable that she doesn’t lash out in retaliation. (She has his number.) But Aydin keeps his physical distance from any imminent peril. When he descends from his aerie into the village in the SUV driven by his faithful lackey, Hidayet (Ayberk Pekcan), the windshield is shattered by the young son of a debtor renter, Ismail (Nejat Isler), upon whom Aydin has sicced a collection agency. Ismail, brutish and boozed up, reacts badly to the intrusion, but it is Hidayet who moves into the fray; Aydin stays out of harm’s way.

Aydin’s disapproval of the people in the village, of practically everyone, has its class trappings. You can see it even in the way he surveys Ismail’s mess of a front yard. He feels dirtied by indigence. And yet Aydin is not a monster. It is Ceylan’s great achievement that he allows us to see the damages of this man. He is pathetic in his imperiousness because, despite his highhanded ways, he is ultimately deceiving only himself. He sees himself as kind, and yet we are continually faced with a scene such as the one in which the furious, rock-throwing boy, ordered to make amends by his obsequious imam uncle Hamdi (Serhat Mustafa Kiliç), is required to prostrate himself before Aydin.

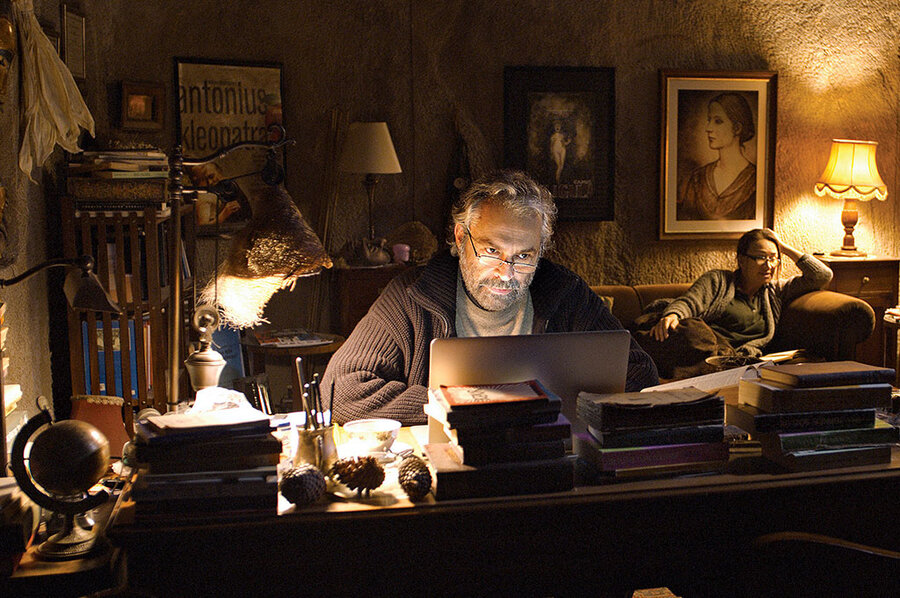

When he isn’t inserting himself into other people’s lives, Aydin spends much of his time in his low-lit study, poring over papers for a book he claims to be writing about the history of Turkish theater. “It will be a thick, serious book,” he intones. He fancies he has a higher calling.

The spaciousness of the winter landscape, captured in magnificent wide-screen compositions, is in stark contrast to the scrunched insulation of the film’s many interior scenes. Ceylan’s set pieces are almost always duets: sometimes between Aydin and his sister, or, most often, Nihal, who has the misfortune of looking her most alluring when she is most despairing. These scenes are talky, yes, but what talk! As these people go at each other, their lives are peeled back for us in a way that recalls not only Chekhov but also Eugene O’Neill, whose writing could be a blunt instrument for sounding the soul. (The soundtrack resounds with repeated refrains from a Schubert piano sonata, which functions as a lament.) The arguments in this movie carry the rehearsed outrage of combatants coiled in endless variations on a theme.

This is why, when Nihal at last goes against Aydin, she is a heroine, even though she bears the stigma of having consented to the marriage in the first place. She must, on some level, have coveted his lordliness; and Aydin, for all his cynical bluster, sees in Nihal a purity that touches him deeply, all the more so because he cannot possess it. Bereft, he is reduced to the ordinariness he had sought to mask. And Nihal realizes that her freedom is more costly than she might have imagined. Her charitableness is thrown back in her face. In this world, it seems, goodness is not enough. Grade: A (This film is not rated.)