Ken Burns co-directs the powerful documentary 'The Central Park Five'

Loading...

In the early morning hours of April 20, 1989, a 28-year-old white female jogger was found gagged and severely beaten in New York’s Central Park. Identified for some time only as the “Central Park jogger,” she lay comatose for several weeks but survived, retaining, mercifully, no memory of the attack.

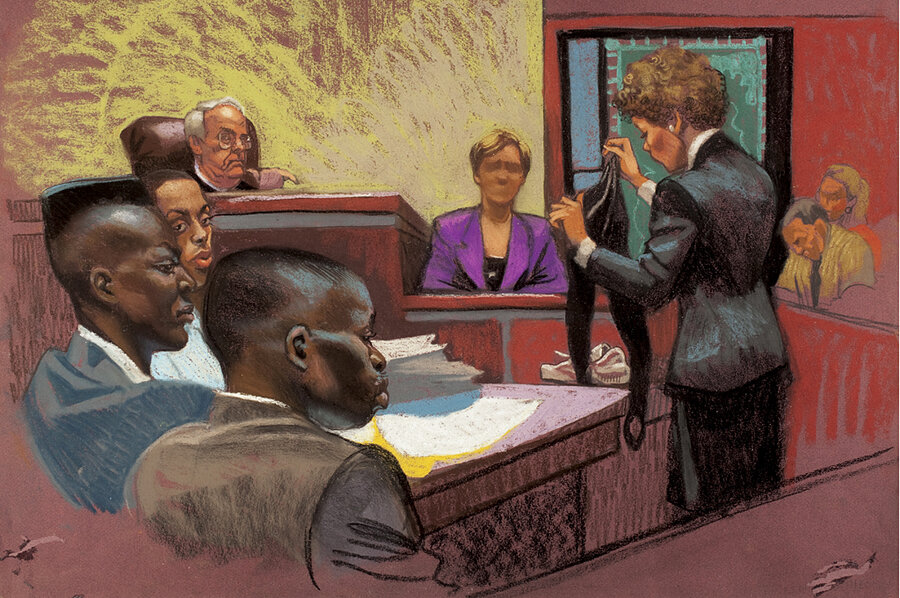

The powerful documentary “The Central Park Five,” directed by Ken Burns; his daughter Sarah Burns; and her husband, David McMahon, is about how the crime, which then-Mayor Ed Koch called “the crime of the century,” was compounded by a rush to judgment against her supposed attackers – the five black and Latino youths, ages 14 to 16, who were coerced by the police into confessing to the assault.

Anton McCray, Kevin Richardson, Raymond Santana, Kharey Wise, and Yusef Salaam ended up serving their sentences, which ranged from seven to 13 years, for the attack before they were finally exonerated in 2002 when a jailhouse confession by a serial rapist and murderer, complete with corroborating DNA evidence, resulted in their convictions being overturned. Soon after, the Central Park Five filed a lawsuit against New York, the prosecutors, and the police who abetted their conviction. The suit is still pending, as the film reminds us in the end. None of the implicated prosecutors or members of the police agreed to be interviewed. The city, meanwhile, in its defense, has tried to subpoena outtakes from the film. And so the ordeal drags on.

The documentary brings to the fore the racially motivated fear that gripped crime-ridden New York in the late 1980s, when the economy was slumping and crack usage and AIDS were on the rise. It wasn’t just the tabloids and the nightly news broadcasts that stirred the caldron; much of the liberal media also jumped into the fray, accepting the five boys’ guilt despite the gaping holes in the case. (It’s a flaw in the film that, besides not hearing from the prosecutors, we also don’t have contemporary interviews with the likes of liberal columnists and former believers Pete Hamill and Bob Herbert, both of whom declined to be interviewed by the filmmakers.)

What we do see, among much else that is damning, are archival NYPD videotapes of the boys being interrogated by detectives who press them to implicate one another in exchange for a leniency that never materialized.

Why would the boys fall so readily in line with these enforced confessions? The film reiterates their own recollection that they were very scared and very naive. (Of the boys interviewed as adults, only McCray chose not to appear on camera, although his voice is heard. We also don’t hear from the jogger, Trisha Meili, who ultimately wrote a book about her experience.)

When I first saw the film at the Toronto film festival, I thought it remarkable that, almost from the start, none of the five held any animosity for any of the others who had falsely implicated them. I mentioned this to Santana, who was attending the festival with the filmmakers. He shrugged and said simply that they all understood how afraid they were at the time.

The improbable beneficence of this attitude is made more understandable when you see what the boys were up against then: the media circus, the fear and loathing. The racial implications of the event were not lost on everyone. If a black woman in Harlem had been found in the same condition as the white upscale jogger, there would have been little public outcry in the press and in the courts.

The documentary grew out of a 2003 internship that Sarah Burns took with a firm preparing a lawsuit by the Five against the city of New York. This led first to a paper for her American studies class at Yale and then, in 2011, to her book, “The Central Park Five: A Chronicle of a City Wilding.” What she and her father and husband have drawn from this material is a combustible amalgam: a movie about justice violated, rectified, and denied. Grade: A- (Unrated.)