Films that presaged the wall's fall

Loading...

| BERLIN

Mauerfall ("wall fall") is what the Germans call it – part of their rich vocabulary to discuss the fate of East Berlin.

As the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall approaches this November, the 59th Berlin International Film Festival paid tribute last week with a series of films that presaged the collapse of socialism.

"After Winter, Comes Spring," a special program of films produced in Eastern bloc countries in the final decade of the cold war, included features, documentaries, animated films, and experimental ones from East Germany, Poland, Russia, Hungary, Romania, the former Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria. After screening in Berlin, the 15-film series goes on a national tour.

The curator, Claus Löser, is an East German native who dismisses the notion that these films explicitly predicted the fall of Communism. "These films are documents of discontent and resistance," he says in an interview. "Of course, they are not prophetic films in a way of seeing exact historical changes. It's more abstract." The films, he adds, "have a healthy amount of disrespect and struck a new note by documenting in film the advent of change."

Dieter Kosslick, the festival's director, makes an even bolder claim: The series shows "how artists can seismographically sense changes ahead of time and incorporate these" into their films, he told German news agency Deutsche Welle.

Above and beyond exhibiting works that are prescient, Mr. Löser intends the series to pay tribute to unsung films and to show that Eastern bloc cinema of the 1980s was producing great art on a level with David Lynch, Jim Jarmusch, and Peter Greenaway. "The central mission of this program," he says, "is to remind about a forgotten chapter of history."

The best-known work is the Polish master Krzysztof Kieslowski's "A Short Film About Killing" (1987), expanded from an episode in his 10-hour-long, "The Decalogue," about a man who commits a senseless murder and is, in turn, executed by the state. The film equates capital punishment to murder.

"It's a good example to explain the relationship between artistic and political messages," says Löser, adding that Kieslowski uses the double killing to represent a laconic and frozen society.

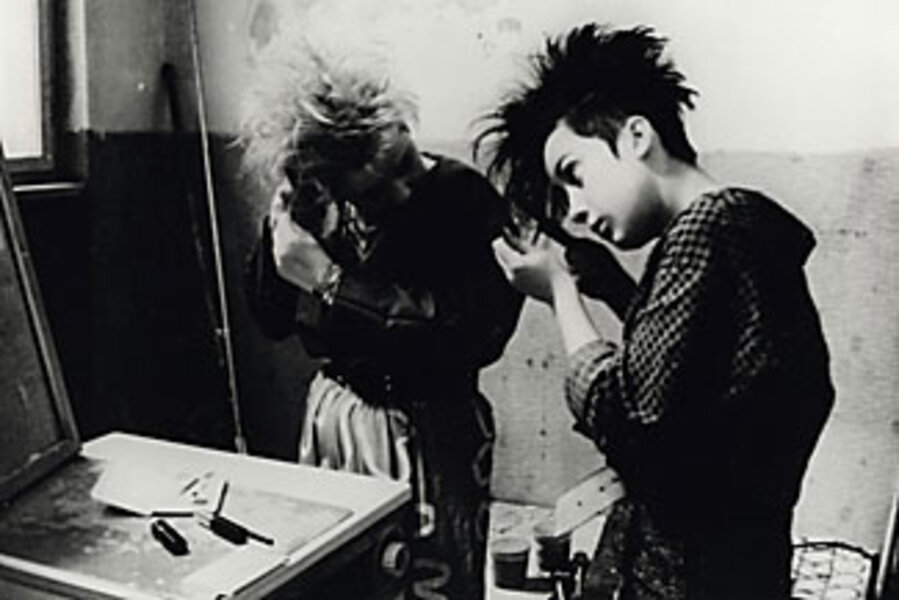

Other filmmakers took a surreal approach to representing social ills and the desire for change. A prime example is director Gábor Bódy's "The Dog's Night Song" (1983), a beautiful film that offers no easy answers. A disconcerting portrait of a Hungarian town thrown into disarray by the arrival of a new parish priest, the film is a web of fragmented and often intersecting narratives: The audience follows a wheelchair-bound veteran of the 1956 uprising unable to commit suicide; an astronomer who moonlights in a punk band; the abused wife of an explosives officer who runs away to join the band; and their son, who films his world with a German tourist's Super 8 camera.

"This film is from the East, but it plays with postmodern terms," Löser says. "You find it in the storytelling, in the changing of the point of view. And you feel very much that something is wrong in this society. The heroes of the film are looking for something, but they don't know exactly what it is."

Many of the films in the series use metaphor to treat themes of occupation and resistance. One such film is "The War of the Worlds – Next Century" (1981), from Polish director Piotr Szulkin, a loose adaptation of H.G. Wells's classic that can be read as a parable for life under a dictatorship. It is unlikely that the references to existing social conditions were lost on the original audience. What is surprising, however, is the parallel with Don Siegel's paranoid classic "Invasion of the Body Snatchers" (1956), which also used alien invasion as a metaphor for communist occupation.

While there was relative artistic freedom in Hungary and Poland by the 1980s, cinema in East Germany and Romania was still heavily censored. Some films were banned outright, such as Rainer Simon's "Jadup und Boel" (1980), about the memory of World War II in a fictional East German town. It was the last film shot at East Berlin's DEFA studios and only released in 1988. Simon did not curry favor with the authorities by pursuing realism and avoiding veiled references to current woes.

"Filmmakers are part of society," says Löser, "so they reflect existing moods. A lot of these films were forbidden for some years because these films had too much reality and that was dangerous for the [Communist] Party."

In East Germany, some directors avoided censorship by making documentaries, which came under less scrutiny than fiction films. One such film is "After Winter, Comes Spring" (1987), by Heike Misselwitz, the nonfiction film about women in East Germany that lends its title to the series.

"It's a masterpiece as a film, not only as a political document," says Löser, who described seeing it for the first time at the 1988 Leipzig Documentary Film Festival, exactly a year before the city's uprisings, which quickly spread to Berlin. "One segment of the audience burst out in applause and the other segment was completely mute, because there were a lot of government officials in the audience," he says. Löser was applauding.

"I was happy, of course, because we always had the hope that maybe a change will come and that it might be possible to work in East Germany as an artist and to stand with an open mind," he says.

The obscurity of the films in the series stems in part from how few directors made films with the same passion after the Iron Curtain fell. (The notable exception is Kieslowski, who continued working until his death in 1996.) Others, Löser says, ceased to find inspiration in a changed world. "It was a great artistic problem if you worked for years and years under very complicated circumstances, and these circumstances vanish. The idea that you are now free to do what you want is wrong. You need to find new coordinates for your work."