Sigourney Weaver having a ball as a 'peacock' in new play

Loading...

| NEW YORK

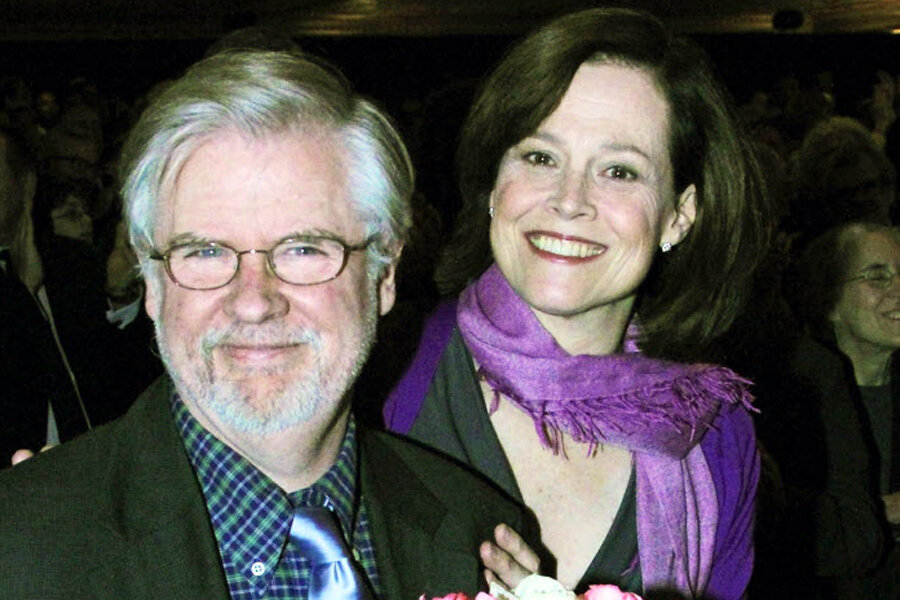

The good news for Sigourney Weaver was that her friend, the playwright Christopher Durang, had a juicy part for her in a new play. It wouldn't even be too much of a stretch — she'd be playing a movie star.

The sticky part: This movie star was overindulgent, self-centered and unaware she's on the decline. She also at one point dons an unflattering old Disney-inspired Snow White costume and insists her friends dress as dwarfs to complement it.

It gets worse: Durang had Weaver in mind when he wrote it.

Perhaps only a friendship and collaboration that has lasted more than 40 years could result in Weaver happily playing Masha these days in the brilliant "Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike" on Broadway, a play likely to score at least a few Tony Award nominations next week.

Weaver, 63, never hesitated about doing the role: "I didn't," she says laughing over coffee at a midtown cafe. "I guess I thought I was different enough from Masha, that I would be fine. And I'm very fond of her."

The play, which played off-Broadway last year and recently made the jump to the Golden Theatre, centers on three middle-aged siblings. Two of them — Vanya, played by David Hyde Pierce, and Sonia, portrayed by Kristine Nielsen — have been sitting around their Pennsylvania home and bickering for years.

The sibling who escaped, Masha, has become an insufferable movie star and has returned with a 29-year-old boy-toy — that would be Spike — to sell the house and pitch her siblings out onto the street.

"Sweetest Vanya, dearest Sonia," Masha says to them when she arrives, looking great, of course. "How I've missed you. You both look the same. Older. Sadder. But the same."

Masha had initially wanted to become the American Judi Dench but got waylaid in a lucrative franchise playing a nymphomaniac serial killer and went through several husbands. "I'm talented, charming, successful — and yet they leave me. They must be insane," she muses.

Masha, whom Weaver calls a "great peacock of a person," needs to be taken down a few pegs and it finally happens, with Weaver slowly coming to the realization that her fussy Hollywood queen act can't last forever.

"It has to be over-the-top at the beginning. It's a performance that she utterly believes," she says. "I feel like an exhausted bird. I think it takes a lot of effort to manifest that kind of persona. When she gives it up, I think she feels better."

Durang, by phone from his Pennsylvania home, quickly makes it clear that Masha was written with Weaver in mind — Masha's franchise "Sexy Killer" is a joke on Weaver's "Alien" movies — but is not based on the actress. He just hoped she'd be available.

"I thought that if, for any reason, Sigourney was free, it would be fun to have her play this self-centered actress," he says. "She doesn't always get to play these grandiose roles. She has such a sense of intelligence to her."

Durang and Weaver met in the fall of 1971 as they entered the Yale School of Drama, he as a playwright who sometimes acted and she as an actress. They had lunch together often, and she appeared in one of his first plays "Better Dead Than Sorry."

"I found that Sigourney in my early stuff tended to be very simple with it," Durang says. "Sometimes it would be very funny because she would say something very sincerely as if it was the most normal thing in the world, but the line would be shocking."

Both graduated in 1974 and two years later reunited for his one-act play "Titanic," with Weaver playing the Captain's daughter. When it moved off-Broadway, the hourlong work was augmented by a cabaret act performed by Durang and Weaver, "Das Lusitania Songspiel," which parodied plays and movies in the style of Bertolt Brecht.

The cabaret on its own became a cult hit and was revived in 1980. In 1986, when Weaver was invited to host "Saturday Night Live," she requested that Durang co-host and they did a little of the cabaret act at the end of the show.

"It is fun to have a friendship that has lasted so long," he says.

She's also been in his play "Beyond Therapy," and they combined to send up self-congratulatory celebrity interviews in an Esquire story in the 1980s that has some kernels of what would later become Masha in "Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike."

"He's such a wonderful, sweet, funny man, and we hit it off right away," says Weaver. "I'm very grateful to Chris. I always love doing his plays, I understood them, and I've felt he had such a distinctive voice."

That might explain why Weaver would jump at playing Masha, who says onstage at one point, with a straight face, "I feel the public doesn't know how heartbreaking I can be. Oh, missed opportunities! Regret, regret, regret!"

"It's so light but it's very demanding," says Weaver of the role. "It's a high-wire act. It's very good for you as an actor but somewhat terrifying."