Can irony really be conveyed with punctuation?

Loading...

Punctuation only gets the spotlight when it misses the mark. Writers rely on punctuation to communicate important cues to readers. Without it, writers risk rambling, misplacing a subject’s prized possession, or even facing a lawsuit, as was the situation in 2014 for Oakhurst Dairy in Maine over a missing Oxford comma. So, in honor of National Punctuation Day, let’s explore some forgotten punctuation.

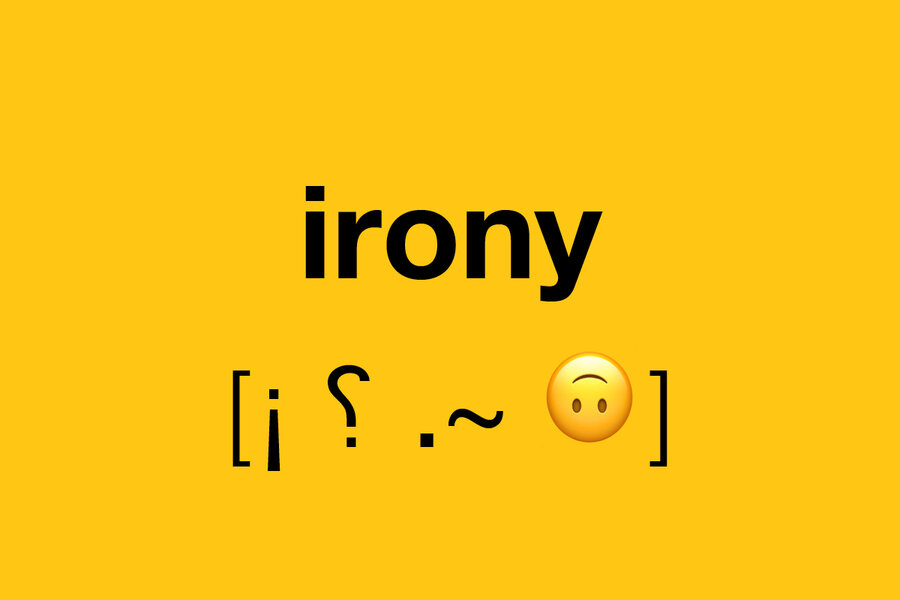

For centuries, wordsmiths have demanded punctuation marks that would convey irony and sarcasm in written text, much like verbal intonation or facial expressions do in spoken conversation. But tipping off readers to phrases with meanings beyond – or even opposite to – what is written has proved challenging.

In the mid-1600s, British philosopher John Wilkins penned the first irony mark, an upside-down exclamation point appropriately resembling a lowercase “i,” which “both hints at the implied irony and suggests the inversion of its meaning,” says author Keith Houston. “Committing verbal irony to paper is fraught with difficulty for both writer and reader,” he writes in “Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols, and Other Typographical Marks.” So punctuating such sentences in this way seemed on point.

Others agreed. Around 1900, French poet Alcanter de Brahm introduced a whiplike backward question mark (⸮) at the start of sentences as a warning to readers that a change of tone followed. But this point d’ironie, or irony point, may have been a step too far, as its placement spoiled the surprise. This piece of punctuation, however, was an interesting follow-up to one by 16th-century English printer Henry Denham. His reversed question mark served as end punctuation for rhetorical questions and was fittingly dubbed the percontation point.

⸮ The irony mark turned out to be a smashing success.

By the 2000s, there was a heightened demand for conveying irony and sarcasm in writing. Enter the snark mark. The list of ironists is hard to pin down, but Slate’s Josh Greenman resurrected the upside-down exclamation point (¡), and typographer Choz Cunningham, among others, suggested using a period followed by a tilde to tell readers that a sentence should be read beyond its literal meaning. The .~ had potential because it was easily rendered by typographers – unlike the irony marks of yore, which may explain their absence today.

All this is to say that punctuation has its purpose. It demands respect, proper implementation, and praise. It’s just too bad we don’t have any current forms of snark marks. ☺️

Casey Fedde is the Monitor’s copy desk editor. In a Word columnist Melissa Mohr is on sabbatical.