Can comity and Comey coexist?

Loading...

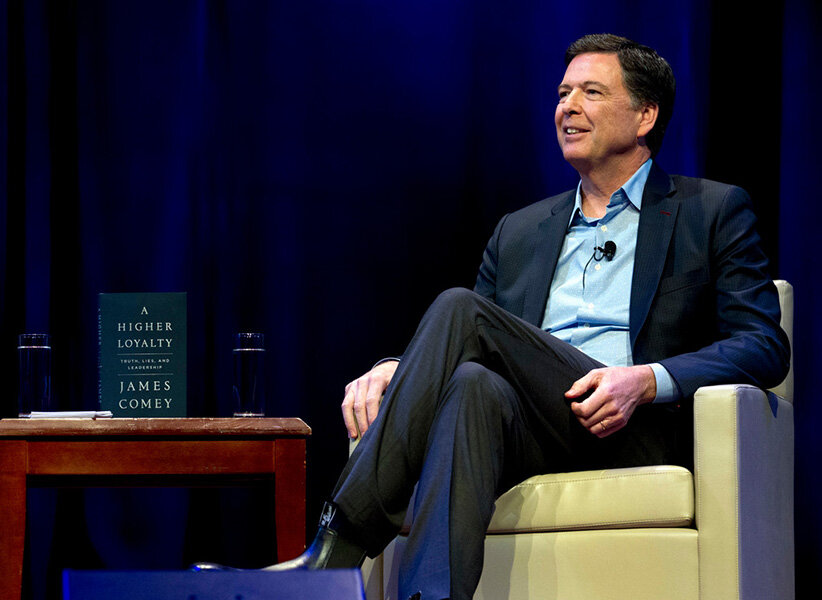

In news articles about former FBI Director James Comey, the word comity appears with surprising frequency. Mr. Comey has been mentioned along with the “comity” of the Senate, of congressional panels, of laws, and even of a White House garden party – “Comity not Comey?” was the headline – last year. It seems to me that this results from word association. “Comey” looks and sounds like comity, so writers move easily from one to the other. We’ll talk more about that next week. This week, let’s look at comity.

In its broadest sense, comity refers to courtesy, to “kindly and considerate behavior towards others,” as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it. A 17th-century etiquette book picked “comity and affability” (ease talking to others; pleasantness) as essential to a good conversation.

Nowadays, though, its use is almost entirely restricted to the political and legal realms. “The comity of nations,” the idea that countries should respect each other’s laws and customs as far as possible, is a guiding principle of international relations. Comity influences relations among US states as well. Legally, it involves reciprocity: You do something for me, and I’ll do the same for you. It means the courts of Massachusetts recognize judgments from Wyoming, and you can drive all over the country on your Wisconsin license.

The US Senate is – or was – strongly associated with ideals of comity. While they are in the chamber, senators employ an almost exaggerated courtesy, referring to each other as “gentlemen” or “gentlewomen” and “esteemed colleagues.” Many of the recent articles about Comey, however, suggest that Senate comity is under threat or already destroyed.

In terms of the more superficial sense of comity, this is not true. The Senate has strict rules of decorum. Rule 19 of the Senate bans insults, forbidding members from “imput[ing] ... any conduct or motive unworthy or unbecoming a Senator” to others. People who worry about the decline of Senate civility perhaps forget that this rule was enacted in 1902 after one senator physically attacked another for spreading a “willful, malicious, and deliberate lie.” Outwardly, the Senate remains overwhelmingly courteous.

But in the more important sense of comity, that of actual respect and reciprocity, things do seem to be going badly. Senators insult each other in interviews and on the campaign trail. Since the 1990s, successive Congresses have struggled to enact laws, partly because partisan scorn puts reciprocity out of the question.

Affability now sounds like a very old-fashioned virtue. Let’s hope it’s not too late for comity.