Cookbook review: 'Food of Life'

Loading...

Persian cuisine has survived Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, and the conquest of Islam. So I figured I couldn’t do too much damage by trying out a recipe or two myself.

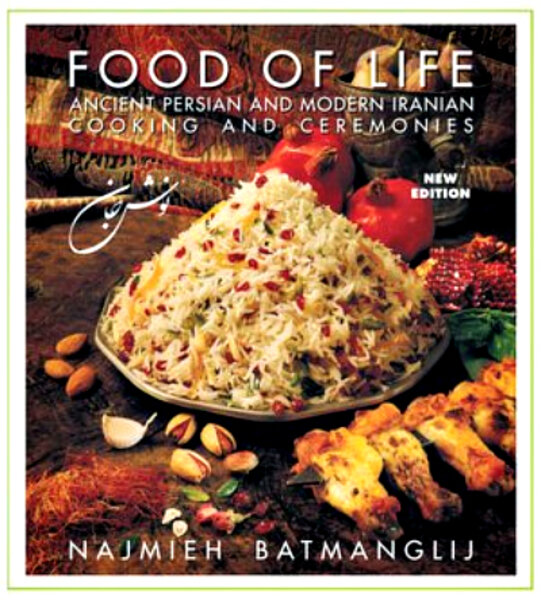

Armed with Najmieh Batmanglij’s gorgeous cookbook, “Food of Life,” I marched into the supermarket to find pomegranate molasses, saffron, and barberries.

Alas, I was in Vermont. In the winter. Nary a pomegranate seed to be found. I did find saffron – in the Mexican aisle. The featherweight package cost almost as much as an upscale lunch in Boston.

Barberries? I didn’t even know what those were. (It wasn’t until later that I discovered the helpful appendices Batmanglij provides, which include a glossary and a list of Persian grocery suppliers around the US and Canada. There you can read that barberries are a small, tart red fruit.)

But I was undeterred – and hungry to know something about Iran besides its controversial nuclear program, which I deal with frequently as the Monitor’s Middle East editor.

With some creativity, and the lenience of my family and our guests – “It’s not like you’re cooking for the shah,” my husband reminded me – we pulled off a respectable version of Jeweled Rice and Pomegranate Khoresh with Chicken, a braised meat dish (see photo).

At a time when the US media seem to have forgotten that there are actual people living in Iran – people throwing snowballs, falling in love, nourishing their friends and families – it could be worthwhile for Americans to get a taste of daily life there.

That has been a key objective for Ms. Batmanglij. The author of five Persian cookbooks, she is from Tehran but has lived in exile since the 1979 Iranian revolution ushered in a theocratic regime. She retains a clear affection for her country, however.

As she says in her preface, her objective with “Food of Life” was “not just to compile a collection of recipes, however delicious they might be, but to share my view of the best of Persian culture. I believe that the same qualities that govern the Persian arts – a particular feeling for the ‘delicate touch,’ letafat – govern the art of Persian cuisine.”

She elaborated on that in a recent phone conversation with me from her kitchen in America’s capital, where many congressmen and think tank analysts are pushing for increasingly harsh measures against the Iranian regime.

“Above all, I wanted Iran associated with good things – pomegranates, saffron, pistachios,” she said. “I wanted to show the best of Iran.”

She does that through gorgeous full-page photographs that include not only beautiful meals but everything from Persian pottery to Persian poetry, revered for centuries – not least of all as a way to express one’s feelings at times of political repression.

“Traditionally people couldn’t express themselves directly so they would use poetry to speak in metaphor,” says Batmanglij, adding that it is so engrained in Iranian society that her mother would even scold her with poetry.

“As soon as Iranians get together they cook, tell jokes, laugh, dance, tell poetry,” she says – and that is what she hopes the owners of her cookbook will do.

The book started out as a love letter to her two sons when they were just babies and the family was living in exile. Now young men, one a filmmaker and the other a member of the indie rock band Vampire Weekend, they encouraged her to update it for their generation.

“Mom, welcome to the 21st century. Your book is old,” she recalls them saying. They helped her restructure and redesign it, adding instructional photographs for some of the more complicated steps.

For those new to Persian cooking, she suggests Fresh Herb Kuku, a frittata, and an adapted 16th -century recipe for pistachio meatballs. She takes the opportunity to exult in the size and color of green California pistachios. “I was so impressed,” she says, noting that the seeds of California’s “Kerman” pistachios came from Iran. (Proof here in this UC Davis study.) When you put it on the table, you can say, “nush-e jan” – which means “food of life,” and is roughly equivalent to “bon appétit.”

If you want to try the real thing – and meet some real Iranians – consult the appendix on Persian restaurants in North America. (At Persian Lala Rokh restaurant in Boston, we were treated not only to sumptuous food but a 15-minute oral tour of the Azerbaijan region of Iran, beginning at the Caspian Sea where fresh fish is caught every afternoon and moving through rice fields, luscious citrus groves, and tea plantations.)

The pickings for Persian restaurants are fairly slim, however. Why is that? Who could resist slightly sweet saffron rice bejeweled with thinly sliced pistachios and slivers of carrot and orange rind?

A key reason is that Iran doesn’t share the same restaurant tradition as the US. Persian food is eaten at home, while restaurants carry foreign foods like pizza and hamburgers.

But it’s also political. After the revolution in 1979, during which Iran kept 52 Americans hostage for 444 days, it was “politically incorrect” to open an Iranian restaurant in the US, says Batmanglij, who says some outlets brand themselves simply as “Middle Eastern” even if their cuisine is purely Iranian.

“Hopefully things will change little by little,” says Batmanglij.

Yes, barberry by barberry.

– Christa Case Bryant is the Monitor's Middle East editor.