Mentoring: Full circle care for elders and youth

Loading...

In the life cycle of a parent, we often transition from caregivers of our children to caretakers of our elders. The luckiest among us discover that by both accepting and encouraging mentorship from our elders, the burdens of care giving can become a blessing.

I grew up in a multi-generational household, so I am one of those people since childhood who has continually had older people among my friends and in my care.

It’s how I became the unofficial wrangler of a number of very persnickety old men who play chess and give their time to teach the game at the free programs I run in Norfolk, Va.

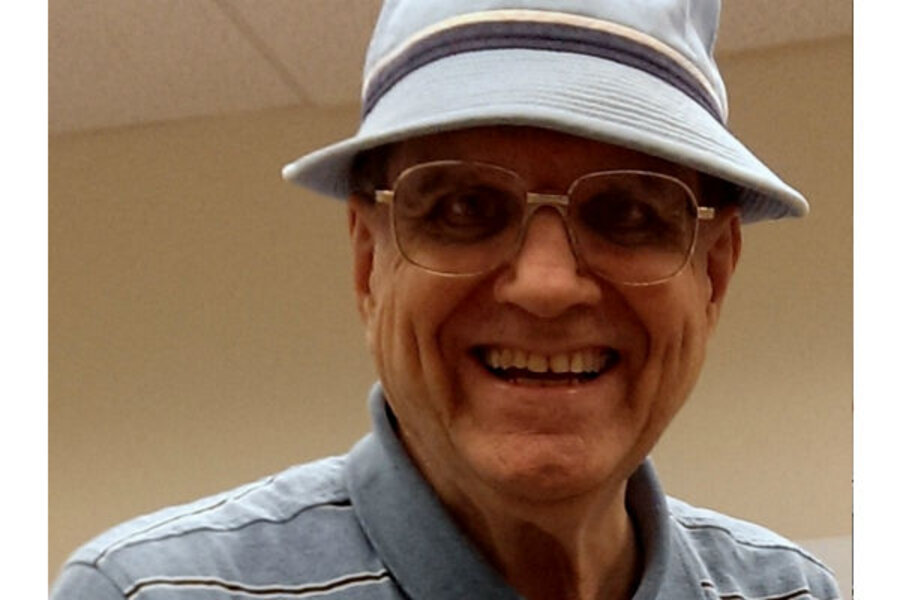

This is how I came to know Gerald R. Ronning, better known as Mr. Gerald, a cranky septuagenarian chess master, who I help a few times a week.

I have made it my practice to drive Mr. Gerald, Miss Daisy, and anybody else who is willing to commit long stretches of their time to kids, to places they need to go.

I counted my blessings for the mentorship Mr. Gerald provides kids, when – like a child – he melted down in Walmart yesterday when he learned they were out of a canned fish favorite called “Kippered Snacks.”

When I met him two years ago at the Lamberts Point Community Center in Norfolk, people ran at the sight of the brooding, critical old badger he’d become over years of mingling only with other seniors.

When he grumbled his way into the chess room, I thought he would explode from the noise, multi-colored chess pieces, and the very casual style of play taking place as 25 kids got cream cheese on the pieces while noshing on bagels as they played.

Today, Mr. Gerald copes by turning off his hearing aids and the kids all adore him. He’s the dude who taught them how to win.

“Well, Mr. Gerald’s crazy, but he knows chess like nobody,” said Ka’lil Leavelle, age 7.

I decided to look into mentoring in America to see how many more Geralds are out there helping.

What I found is that only a fraction of the 41.4 million seniors in the US are involved in family and community mentor relationships, according to David Shapiro, chief executive of the National Mentoring Partnership (NMP) based in Boston, Mass.

According to Mr. Shapiro, a series of studies over the past decade revealed that only 4.5 million at-risk kids are growing up with mentors who are either “naturally occurring” or “program-based.”

A “naturally occurring mentor” is someone like a grandparent or coach who takes an interest in a child. A “program-based mentor” is someone like Mr. Gerald, who meets kids via a club or organization.

“Every great parent, whether they are coming from a place of disadvantage or of plenty, is looking for additional assets in the form of those mentoring relationships for their kids,” Shapiro says.

The National Mentoring Partnership works to connect both those who need mentors and those who want to become mentors with resources in their area.

Shapiro also reminded me that senior Americans are just a fraction of the potential mentor population, pointing out, “You’re a mentor and the mom of four kids, right?”

Excellent point.

“We’re the United Nations of Mentoring,” Shaprio says. “We work connecting people across the board -- from Big Brother/Big Sister to AARP Experience Corps to the Boys and Girls Clubs.”

I have a special place in my heart for seniors who decide to share their wit, wisdom, and experience with kids and young adults.

NMP released a report last year called The Mentoring Effect that surveyed young adults ages 18-21 nationwide, asking them to reflect on their childhood mentoring experiences. It found that at-risk young adults who had a mentor are:

- 55 percent more likely to be enrolled in college than those who did not have a mentor.

- 81 percent more likely to report participating regularly in sports or extracurricular activities.

- 78 percent more likely to volunteer regularly in their communities.

I know from personal experience that mentoring works wonders for both the mentor and child.

After my parent’s divorce when I was age 9, my mother, younger brother, and I shared a home with my grandmother and great-grandmother in New Jersey.

Grandma ran a series of workshops on quilting at a local community college, and mentored young people on sewing and quilting. She also ran a weekly quilting circle that met at our house.

“It keeps me young,” Grandma would say.

I remember the enormous quilting frame in the living room and different generations coming together around it.

This gave me more mentors than I could shake a stitch at, teaching about me everything from world history to job interview skills.

When my fingers tired from needlework, I would retreat under the quilting frame where I lay down and looked up at the light coming through the needle holes, like stars shining in the sky.

I would fall asleep under the quilting frame, and later under another of our quilts on my bed, dreaming of someday having being the grandma with a coffee klatch of my own.

Today, I’m a mother to four boys, and quilting afternoons have been replaced by founding a free chess club with senior citizen mentors and kids of all ages.

When anyone asks me how I manage to keep 20 or more kids and half a dozen fussy older mentors in check, I smile and remember where I learned my tactics.

My Grandma Annie was a master at controlled chaos who kept a living room full of competitive, sharp-eyed, sharp-tongued Golden Girls running smoothly as they meshed with the younger generation, two grand-children, and a yappy collie named Laddie once a week.

Grandma taught me to always make sure there is plenty of food, enough to feed everyone and keep mouths too busy to complain or argue.

That’s why we serve bagels with a side order of chess mentor every week at the community center.

Seeing Mr.Gerald and Ka’Lil, I realize that you are never too young or old to become a mentor and that everyone likes bagels.

No matter what age you are, when you begin sharing your time, talent, and experience, you can be sure the impact will live on long after you.