School report cards, then and now. What's changed?

Loading...

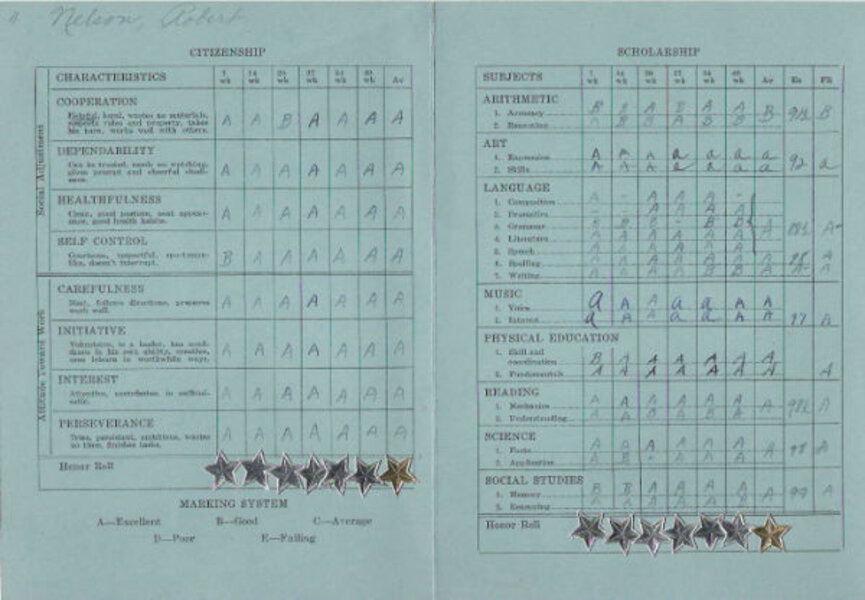

If you were a fourth grader at the Eggertsville Elementary School in Eggertsville, New York, in the 1930s, citizenship occupied fully half of the small blue report card that you took home to your parents at the end of each marking period – six times a year. And your parents signed it and sent it back. And these reports – my father’s – would be saved for posterity.

Citizenship was complicated! It was divided into two parts: Social Adjustment and Attitude Toward Work, both categories detailed in subcategories: cooperation, dependability, healthfulness, self control, carefulness, initiative, interest, and perseverance, respectively. Even the sub-categories had sub-categories. The standards were clear and concise; the routine rigid; the document short and graphic. And there were silver stars to be earned, as well as letter codes: U, I, S, H!

Over on the “Scholarship” side of the blue card, the headings listed the academic subjects without sub-categories. Everyone seemed to know what was included in math, science, language arts. There were the traditional letter grades for each subject, and an average grade for the year. Stapled inside, was a very small blank piece of paper with room for the teacher’s “remarks,” if they chose.

“Bob did some fine work on the original Columbus Day play,” wrote Mrs. Shurgot. The year before: “Bob did some good acting in the class Thanksgiving play.” And in the Christmas assembly, “he showed more of his good work on the stage by the fine reading of his topic and poem.” I suppose we would call these “narrative comments” today. What was the name of that poem? What made his work on the play “fine”? It feels like incomplete reporting. There’s no directive information in them for the next marking period. I want details!

The Eggertsville card also contains one brief, statement of mission: “When the school and home unite in their efforts the best interest of the child can be served. The closest cooperation of these two forces is essential for the pupil’s development.” So, it’s a progress report! But what a starchy declaration of interdependence.

At any rate, young Bob took that card home six times and returned it to school with his mother’s signature. He was promoted to fifth grade, with many silver stars attached for good attendance, honor roll, band, music, newspaper. Evidently Bob’s mom valued her son’s record of achievement and saved all his report cards. They were preserved for posterity. Bob’s mom was June Nelson, my grandmother, and I hadn’t seen these historic artifacts until a recent Thanksgiving, when we had a good laugh over dad’s academic record around the family table.

What a role reversal. I was glad to see Dad’s progress from third grade music, when he got an I for “improving” in the “sings with pleasing quality” sub-category in music. The next year he took up trumpet, and avoided the whole singing issue. Back in kindergarten he had gotten a U (unsatisfactory) for “plays and works well with others,” and a U for “listens while others are talking, does not interrupt.” But by third grade, he cleaned up his act and was getting all H's (for honor), particularly noteworthy in the area of “volunteers and does his part in making school profitable and interesting.” All that emphasis on citizenship and civility was paying off.

Some things never change. A progress report form is still an expression of a school community’s values and relationships, as well as individual achievement. Judging by the space allotted to it, citizenship had value equal to scholarship in Eggertsville. The community knew what it wanted, and had a system for accountability.

Some things ought to change. My grandparents couldn’t tell what my dad was reading and writing in grade school, or how math concepts were taught. And I’d like to hear more of the voice of his teachers telling the story of those years—especially since he had his beloved Mrs. Shurgot for three years in a row. There should be a balance between data and eyewitness news; hindsight and foresight.

In 1942, Bob won second-best in the Buffalo Evening News Spelling Bee. He was on the road to becoming Robert C. Nelson, a journalist. But I’m more amused to know him as the kindergartner who got a U in playing well with others.

Family archives can be terrifying. Someone managed to save my tenth grade French teacher’s comment: “Very little effort expended in or out of class. C-.” Incomplete reporting! My own eyewitness news account would mention expending a lot of effort that year. Two years later I got a 750 on my French achievement test. Good data. And recently I’ve made a lot of new friends in France. “Ms. Hornbeak, would you revise my grade? I wasn’t done!” So it goes. Progress reports have transitory meaning, for some purposes, and remain priceless, if frozen in time, for others. I just hope mine don’t show up at some future Thanksgiving table.

Todd R. Nelson is Head of School at The School in Rose Valley, Pa.