Father's Day gifts of conversation: from poet Yevtushenko to a jobless steelworker

Loading...

| Philadelphia

My father could hold a conversation with anyone. Some of my favorite recollections are of him doing just that. His print, radio, and television journalism career took him to myriad places and stories in 40 years of reporting. He earned a living starting conversations with unlikely people, in unlikely places.

In Chicago he won an award for covering ward politics. He traveled to the southern states at the height of the civil rights movement, and then years later to Ulster at the height of The Troubles. He had plenty of conversations with famous newsmakers, and with the man in the street and the common people behind the news. He put an intimate, familiar face on the big, seemingly remote stories of several reporting eras. [Editor's note: The author's father, Robert Colby Nelson, was a long-time correspondent and editor for The Christian Science Monitor.]

Through his art of conversation, his readers found the heart of a shared humanity. Dad could talk with white men, black men; Protestants, Catholics; the mighty and the downtrodden; rich and poor. Strangers became friends; the untrusting, trusting.

On any given casual outing, dad struck up conversation. He loved to talk with the London cabbies during our years in England, learning about The Knowledge of London driving routes, and the day’s politics or most recent trade union action.

But two particular conversations stand out to me: one of the earliest I remember from my youth, and one I know of only through a photograph.

Dad hated fishing. But when I was about nine, he took me fishing not far from his boyhood home in Buffalo. I think he felt a certain duty to indulge my interest, and so we set off with an old rod, hooks, and worms, to sit beside a creek. The fish weren’t biting, but the thin slate rocks on the creek bed were worthy of a few hours spent skipping stones while watching the bobber.

The more powerful memory is of dad’s conversation with the unemployed steelworker sitting on the bank nearby, also watching his bobber in the current.

The gist of their conversation never made any sense to me. But I see it now as my earliest recollection of dad’s professional voice.

I can remember the tone of the men talking, the feeling of the heavy summer air, and a certain slant of light filtering through the trees above. And as with many of dad’s subsequent conversations, I remember the earnest quality of the transaction. Dad was curious about the stranger’s story. The steelworker found someone who took a genuine interest in his lot, and he opened up. There was a bridge, and strangeness couldn’t persist.

It’s not that the journalist in my father was always seeking the story potential in anyone he met, but that he simply saw the truth in everyone’s story and wanted to hear it. There was always the possibility of arriving at the point where one could say, “I know you. I see you.” Familiarity.

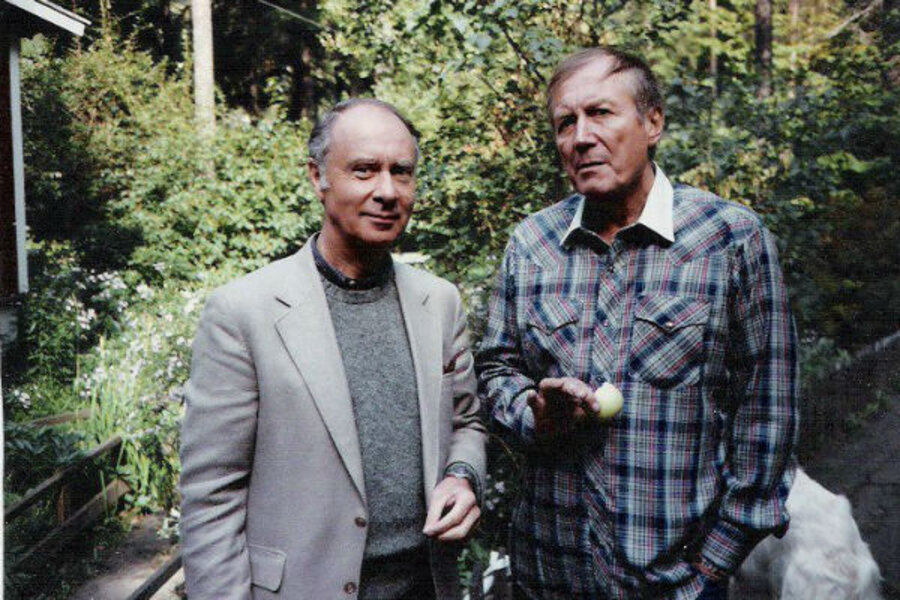

The photo I cherish comes from the 1980s during one of dad’s trips to Russia. He was no doubt fulfilling a longstanding dream of interviewing poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko. Dad studied Russian in high school and college, then got a master's degree in Soviet studies, preparing himself for the big story of his era: the cold war, and Soviet-American relations.

In a later phase of his career, he was a journalist attached to the Kettering Foundation’s Dartmouth Conferences, and made numerous trips to Russia as a member of high-level discussions and exchanges. I love his photos of visits to St. Petersburg, the Hermitage, and his tales of life in the waning years of the Soviet Union.

But this photo is different. It’s a small story. The two men must be at a dacha. There is spring foliage. Dad stands beside Yevtushenko. The poet is holding an apple and obviously in mid-sentence. He is expounding. Dad has obviously set his camera on a tripod and used the self-timer, then dashed into the frame. He directs his gaze straight into the lens. His expression suggests he is thinking, “How cool is this. I’m standing next to Yevtushenko.”

He is mid-conversation – with the poet, with himself, with the audience for the photo… with me. And I know the tone of voice that characterized the afternoon of questions and answers, the sharing between the American journalist and the Russian poet, as their stories became real to one another. To dad, journalism itself was a conversation, and the big story could be as present in the tale of the steelworker as in the expounding of the great poet.

RELATED:Are you a Helicopter Parent? Take our quiz!

There is, of course, a third conversation to relate, and it’s ongoing: my own, with my father, in each opportunity to hear someone’s story. I too ask the cabbies, with immense curiosity, where they’re from. Thanks for the conversations, dad.