The new normal in adoption: Birth parent no longer secret

Loading...

| New York

The secrecy that long shrouded adoption has given way to openness, and only about 5 percent of infant adoptions in the US now take place without some ongoing relationship between birth parent and adoptive family, according to a comprehensive new report.

Based on a survey of 100 adoption agencies, the Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute reported today that the new norm is for birth parents considering adoption to meet with prospective adoptive parents and pick the new family for their baby.

Of the roughly 14,000 to 18,000 infant adoptions each year, about 55 percent are fully open, with the parties agreeing to ongoing contact that includes the child, the report said. About 40 percent are "mediated" adoptions in which the adoption agency facilitates periodic exchanges of pictures and letters, but there is typically no direct contact among the parties.

"The degree of openness should be tailored to the preferences of the individual participants," said Chuck Johnson of the National Council for Adoption, which represents about 60 agencies. "It points to the huge importance of the right people being matched with each other."

The Donaldson institute, citing its own research and numerous other studies, said most participants find open adoptions a positive experience. In general, the report said, adoptive families are more satisfied with the adoption process, birth mothers experience less regret and worry, and the adopted children benefit by having access to their birth relatives, as well as to their family and medical histories.

"The good news is that adoption in our country is traveling a road toward greater openness and honesty," said Adam Pertman, the institute's executive director. "But this new reality also brings challenges, and there are still widespread myths and misconceptions about open adoption."

The challenges, according to Mr. Pertman and other adoption experts, often involve mismatched expectations as to the degree of post-adoption contact. The Donaldson report recommends counseling and training for all the adults involved, as well as post-adoption services to help them and their children work through any problems that arise.

The president of one of the largest US adoption agencies, Bill Blacquiere of Bethany Christian Services, said his staff encourages expectant birth mothers to meet with the prospective adoptive family to discuss the array of options for an open adoption.

"As much as possible, we allow the parties to design that themselves," Mr. Blacquiere said. "We mediate to make sure both parties are getting what they need."

The post-adoption relationship may start out warily, then become more comfortable as time passes, but Blacquiere said each party should keep the other's expectations in mind even as circumstances change.

"For adoptive families, they need to make sure they live up to their commitments, and not try to go back on their initial agreement," he said. "On the birthparent side, they need to remember that this isn't co-parenting – part of their role has to be blessing the new home that their child has."

One common pattern, according to adoption agency officials, is that the birth parent initially wants more frequent contact with the child than the adoptive family prefers, followed by a gradual shift.

"When the children get older, it's often the adoptive families wanting more contact, and the birthparents may have moved on in their lives and at that point are interested in less," said David Nish, director of adoption programs for New York-based Spence-Chapin Adoption Services.

Mr. Nish said Spence-Chapin espouses the principle of self-determination in working with birth mothers on their hopes for post-adoption arrangements. But he said the agency won't work with adoptive parents who insist on having no contact with the birth mother.

"We try to educate them," he said. "If they're really set on it being closed, we tell them we don't do closed adoptions."

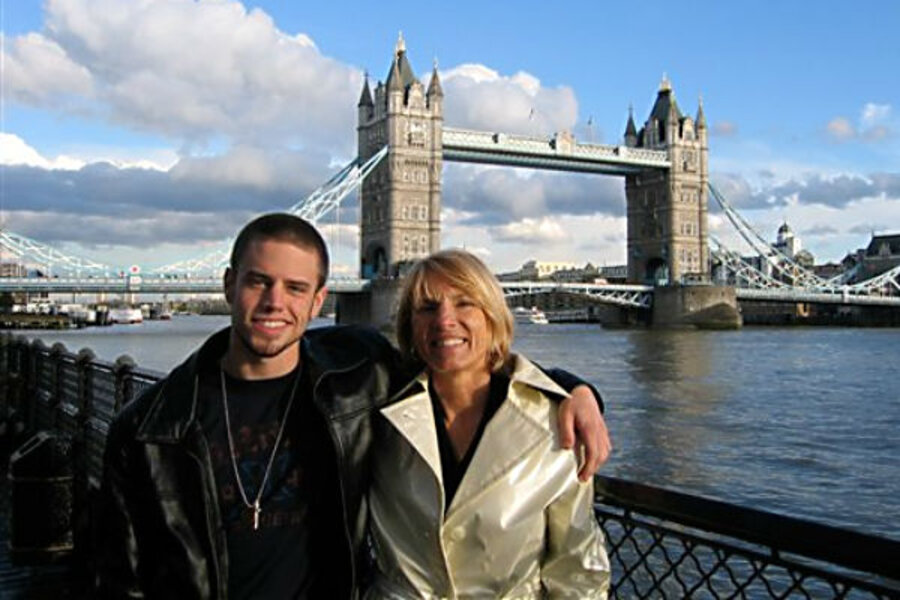

For Dawne Era, a psychotherapist from Warwick, R.I., the decision to embrace an open adoption evolved step by step 23 years ago when she and her husband decided to adopt after unsuccessful attempts to conceive on their own.

They made contact with a pregnant 18-year-old from Nebraska who'd decided to place her baby up for adoption, then got to know her as the young woman spent her pregnancy in nearby Boston.

After the birth and adoption of a baby boy named Grady, the birth mother and the adoptive parents agreed to remain in contact. It was an informal pact, yet it led to a mutually satisfying relationship that has continued throughout Grady's life – occasional phone conversations, a handful of face-to-face visits and, more recently, ongoing contact via Facebook between Grady and his birth mother and his younger half-sister.

For Ms. Era, there was a stressful moment when she and her husband got divorced while Grady was a toddler, and she had to inform the birth mother.

"That was very difficult," Era said. "We had promised to take Grady in and raise him in a two-parent family. I thought she would be very disappointed in me, but she took it well."

Overall, said Era, the open adoption "has been very positive for all of us."

Mr. Pertman of the Donaldson Institute has a daughter adopted 14 years ago. He said challenges can sometimes arise even after adoptive parents and birth parents grow comfortable with the rhythms of an open adoption.

He recalled how many members of his daughter's birth family – including her birth mother, grandparents, a brother and an uncle – came to her bat mitzvah.

"For us and them it was normal, but not for everybody else in the room," Pertman said. "They got some looks, like 'What's this all about?' "