‘Water connects all of us’: Black artists create a new relationship with the sea

Loading...

| Charlotte, N.C.

Heartbreak and tragedy often accompany interpretations of Black people and the Atlantic Ocean. Stories of the transatlantic slave trade, or the “Door of No Return” in Ghana that Africans were forced through, are heavy. How could they not be?

And yet, the power of water and sounds of the sea can also provide a sense of solace and triumph. That vision is featured in “Becoming the Sea,” a new exhibit at the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture in Charlotte, North Carolina. The works on display – which include paintings, photography, writing, and video – are generated by Black Rock Senegal. The international artist-in-residence program was founded by Kehinde Wiley, known for his portrait of former President Barack Obama, in 2019.

What the 12 artists have produced toggles between present and future, the everyday and the fantastical.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe relationship between Black people and the Atlantic Ocean is often a heavy, tragic one. But artists in “Becoming the Sea” use the exhibit as an opportunity to reclaim and transform the water narrative.

“I really saw a lot of deep hues with the colors that were being used. It spoke to our existence, not just in skin tone, but just the blues that are continually playing in our livelihood,” says Shawn Allison, a Charlotte-based blogger and culture critic, in a phone interview. “But at the end of the day, there’s still that joy that we have as Black people … and no one can take it away.”

A palpable sense of joy – and sustenance

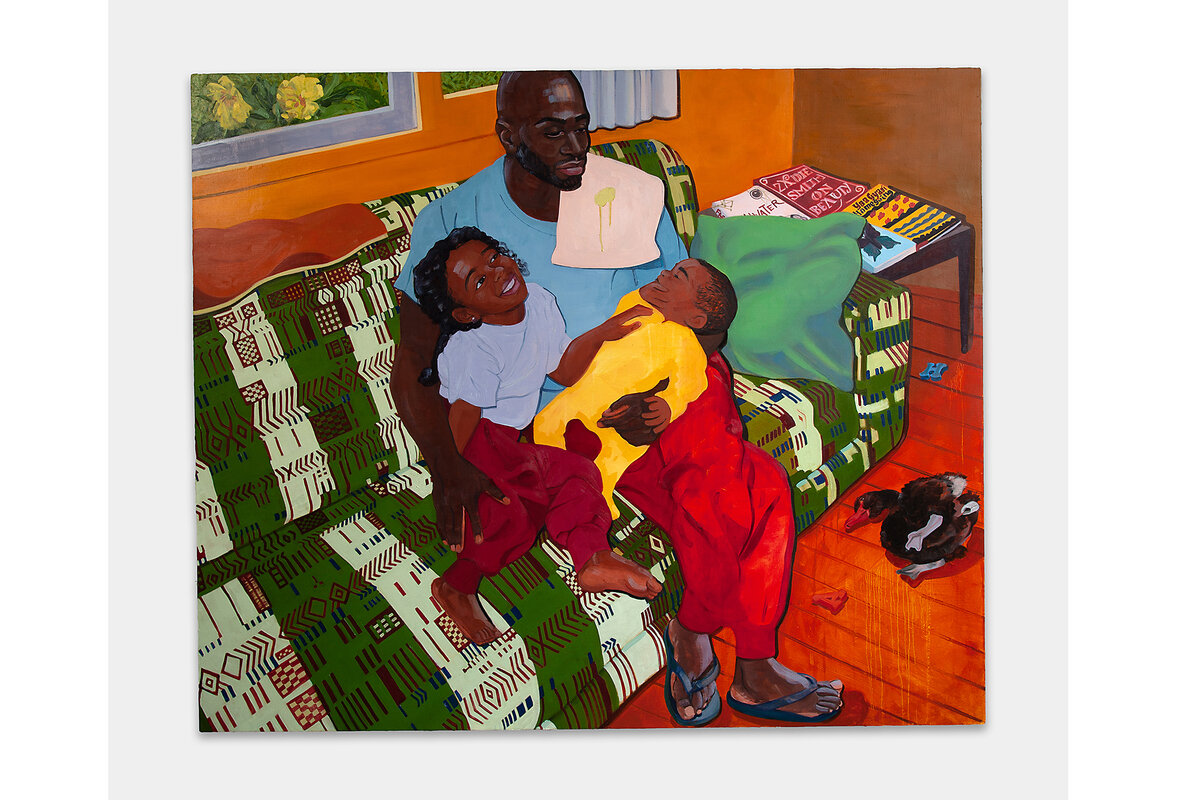

That palpable sense of joy and responsibility bursts out of one particular painting. In it, a Black father is caring for his children. That might not be an image associated with aquatic themes, but curator Dexter Wimberly sees a direct correlation between “Not Without Laughter,” by Tajh Rust, and a glorious purpose.

“[It] resonated with me because it’s rare to see portraits of Black fathers with their children. It was imperative for me to put that in the show,” Mr. Wimberly said in an interview with the Monitor during an opening celebration for the exhibit on Aug. 9. “It connects to the title in the sense that water connects all of us in a variety of ways. It’s also a sustaining body – a thing that keeps us alive. Parents keep their children alive.”

Despite the prominence of a burp cloth on the father’s left shoulder, there is a regality to Mr. Rust’s piece. The patriarch is a towering figure with dark skin, cradling his young daughter and infant son. The couch they are sitting on has an African motif, and a nearby table holds pieces that are influential to Mr. Rust. One of those is “Homegoing” by Yaa Gyasi, a book of interlinked tales that tell the very real stories of the slave trade and effects of trauma over decades.

As Mr. Rust, the artist, sees it, water offers a universality and presence – a place to begin when telling a story.

“I think water is one thing we can all look to, to talk about a common ancestry, a shared mobility. But water, the ocean I should say, it’s fun to paint, on an aesthetic level. It holds a lot of meaning, and it’s fluid,” he says in a video conversation with Mr. Wimberly released by the Gantt Center.

Painting women as “supernatural beings”

In “Becoming the Sea,” artists push and pull on the past and the future. The exhibit taps into the genre of Afrofuturism, a movement that melds science fiction with Black history and culture. The concept has been around for generations, but the ideology received a boost from Marvel’s 2018 blockbuster “Black Panther,” which envisioned the technologically advanced African nation of Wakanda.

Grace Lynne Haynes, whose work has been featured in The New Yorker and on PBS, found inspiration in a quote from jazz musician Sun Ra. In the song “Somebody Else’s World,” he writes: “Somebody else’s idea of somebody else’s world is not my idea of things as they are. Somebody else’s idea of things to come need not be the only way to vision the future.”

Ms. Haynes took that freedom to heart – and to her art. What resulted are a pair of water-themed pieces with sea-based imagery. What really makes the canvas come alive is her interpretation of Black women. They aren’t earthly beings, with traditional limbs. They are otherworldly, and even within the paintings, far removed from what we would consider everyday life.

“The women that I paint are supernatural beings. They don’t hold the pain and traumas of the world that we’re in. They are associated more with their ecologies and their environments,” Ms. Haynes said in an opening night conversation with Mr. Wimberly, the curator. “And so as they move their hands together, they’re able to intermingle with nature, with the fish, the ocean. In this world, I’m thinking about how we intermingle with different species and also learning to decenter humans. … I’m thinking about how I can incorporate more of our planet, the world, and other species into the work.”

Culturalist Ytasha Womack is a leading voice on the concept of Afrofuturism. She also is among the artists featured in the exhibit. Ms. Womack created a zine called “Fluid,” which she has said deals with water mythos.

“The value of Afrofuturism is that it reminds you that African diaspora cultures, like all cultures, have a space-time relationship,” the author says in an interview with the Monitor. “It’s evident in language, in storytelling, how people gather. It’s in the art, it’s in the music.”

How does a Black future correlate with “Becoming the Sea,” then? It’s simple. Water isn’t just life. It can also symbolize the afterlife – an understanding and appreciation of history in a way that uplifts and liberates.

“When you think about African diasporic relationships to spirituality, water comes up a lot. If you’re Christian, it’s baptisms. In the Congolese cosmogram, there’s a river that separates the seen and unseen worlds,” Ms. Womack says. “Of course, water is central to life. ... But water, in a lot of Western ideas, symbolizes the subconscious. So it’s this idea of pulling from the subconscious and creating something new, which lends itself to a lot of great art and conversation.”