What is art? A New Hampshire bakery stands up for its muffin mural.

Loading...

| Conway, N.H.

When Sean Young offered up the wall of his bakery as a canvas for the art class at the local high school, he didn’t think much of it. Three students went to work, creating a colorful mural of the sun rising over the White Mountains, depicted as muffins and doughnuts. Mr. Young loved it, he says. His staff at Leavitt’s Country Bakery loved it, and customers loved it.

The town of Conway, New Hampshire, however, did not. The painting was cited by the town code enforcement officer in June 2022 for violating the sign ordinance for its size. The painting depicts baked goods, which opponents say makes it not art – which is protected by free speech – but advertisement.

Mr. Young’s application for a variance was denied, and a Virginia-based law firm, the Institute for Justice, picked up his case.

Why We Wrote This

Where is the line between art and advertising? A New Hampshire bakery’s mural has inspired a debate among the residents of Conway about private property and public art.

A classic New England town hall debate ensued – one about free speech, private property, and local governance. Locals flocked to attend meetings for both the Zoning Board of Adjustment and the Planning Board to voice their views on the mural, or sign. It’s a question of when art becomes advertisement. And on April 11, citizens voted 788-736 against a proposed change to the sign ordinance that would have incorporated murals and works of art.

There’s no clear division between art and advertisement, says Michele Bogart, professor emeritus at Stony Brook University. (Take, for example, Andy Warhol’s Campbell Soup canvases.)

“[Leavitt’s] is a very interesting, complicated case about taste and property rights and ... an interpretation that this is advertising versus a case of it being community art,” says Dr. Bogart, whose specialties include the social history of public art.

It’s not the object of public art that matters in the end as much as the process of making it and who that involves. “It’s not simply what the work looks like. It’s what it embodies,” she says.

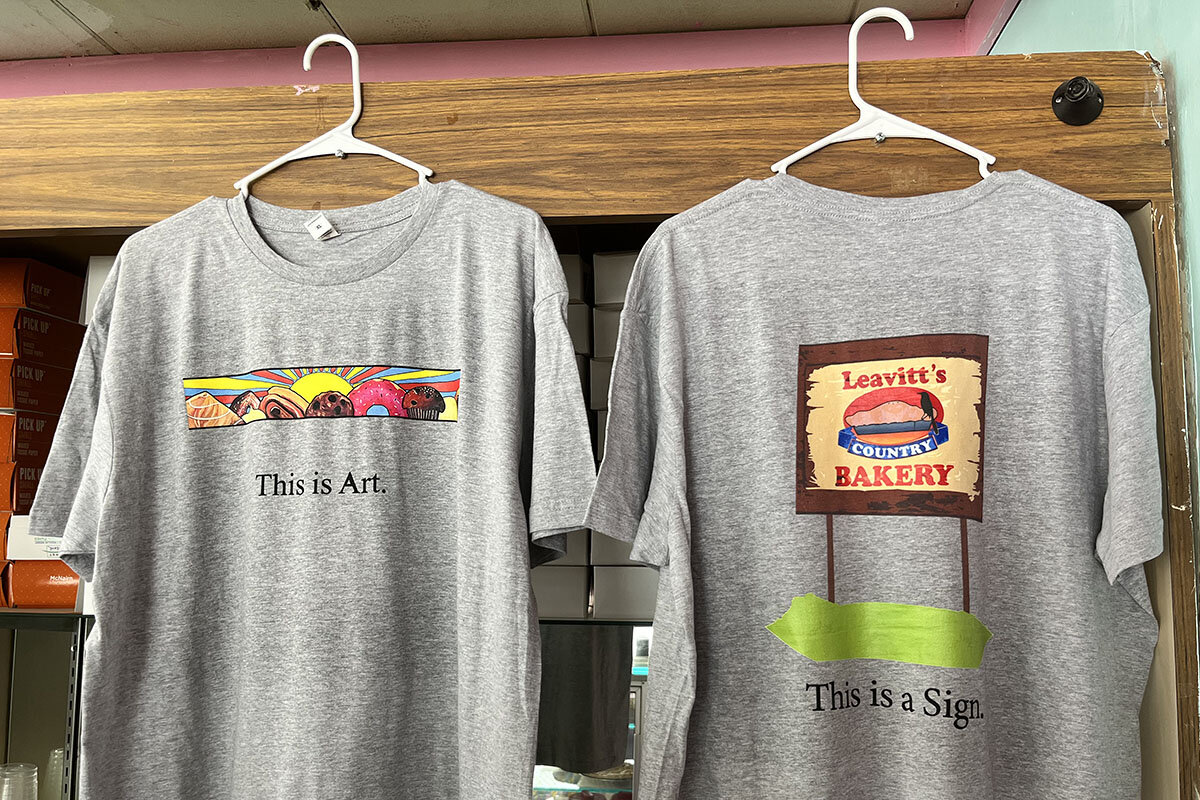

Since fighting for the right to display what Mr. Young maintains is a mural, Leavitt’s has become an advocate for the arts. The bakery recently began selling T-shirts with the mural on the front above the words “this is art,” and the Leavitt’s sign on the back with, “this is a sign.” Proceeds benefit the Kennett High School art department. And with the help of a local philanthropist, Leavitt’s is co-sponsoring a scholarship for one student a year from Kennett High who wants to pursue the arts.

“I’m not taking it down because it’s the kids’ artwork,” Mr. Young says.

For now, the painting stays. As long as the town interprets its sign ordinance in a way that outlaws the painting, the Institute for Justice plans to move forward with its federal case against the town on Mr. Young's behalf.

The town stands by its decision to cite the bakery, says town manager John Eastman. “The ordinance is lawful, and it is based on size, not content.”

If locals don’t like the ordinance, he says, they should submit a petition to change it – as was on the ballot. “The ordinance was voted in by the people. [Government] didn’t just arbitrarily make this up to hurt people.”

Although the town says its enforcement is now based on size, not content, Leavitt’s and the Institute for Justice maintain the opposite, saying the town’s focus was at first on content. “Mr. Hebert asked if the town’s position was solely on the graphic of the donuts and the muffins. Mr. Gibbs answered in the affirmative,” read the minutes from an Aug. 17 meeting, reflecting an exchange between a member of the board and the code enforcement officer.

Mr. Young bought Leavitt’s a year ago from the original owners. A local fixture famed for its hand-cut doughnuts, lines go out the door in peak season and employees have memorized the orders of regulars.

Public art is important for many reasons, not least of which is that it creates a sense of place, says Boston-based muralist Caleb Neelon. “It’s like remembering the color of your kitchen when you’re growing up,” says Mr. Neelon. “It’s going to be something that means home.”

Luminaries like Banksy or Diego Rivera aside, there are two general types of public art, says Mr. Neelon. There are the projects that receive funding and go through a public approval process (think: the much-debated Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King memorial in Boston), and there is the grassroots type, which is often a property owner offering up a wall as Leavitt’s did.

The latter type “tends to be something where people like seeing them and they are fun, a little bit contagious in the sense that people like to paint big and it’s fun to do,” he says.

Emma Gallant, one of the students who painted the mural, is a junior at Kennett High and now works at Leavitt’s.

“I’ve always really loved art. It’s something that I plan on doing throughout my life, even after I graduate,” says Emma. “When my art teacher told me that we had an opportunity within the community to paint a big piece for a local bakery, I got really excited.”

The students weren’t told what to paint, Emma says. The three of them came up with the concept after a week of brainstorming. So the debate over whether to remove the mural “kind of hurts,” she says. “I wish art could just be art.”

A mother of three, Autumn Santagata says she is concerned about the impact the pandemic had on students’ mental health. She sees the mural as the type of action that should be supported – “let’s keep them on the right path.”

“We should lift them up,” not tear them down, says the bakery employee.

Many Conway voters walking into the town’s polling place Tuesday say they are fans of the painting. Others, however, feel the ordinance is fair and that Leavitt’s should comply.

Mark Hounsell, a member of the planning board who voted in favor of the proposed change, was debating with Carl Thibodeau, a member of the board of selectmen.

The ordinance as it stands is not enforceable, says Mr. Hounsell. The selectmen can suspend enforcement if they believe something is unjust, he says, and he believes they should have done so.

Mr. Thibodeau agrees that the sign ordinance needs to be rewritten, but the changes suggested were “too ambiguous.”

“The other side of it is that if they start putting up these giant murals all over town, and if you can’t call them a sign, then you can’t stop them, and I don’t know that anybody wants that,” he says.

“No,” agrees Mr. Hounsell, “but I don’t think anybody wants what we have.”

Most Conway residents are happy to talk about the bakery. “I love the mural,” says Jeanne Twehous, a nurse at the high school. “I don’t see any downsides to it, and I’m still not sure why it became an issue.”

“Personally, I think it’s not a sign,” says Dino Scaletti, who has split most of his adult life between Conway and Maryland, where he worked for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. “Whether he makes bagels or doughnuts doesn’t make any difference to me.”

Deborah Fauver, a retired lawyer, is more conflicted. “It’s a tough problem,” she says, saying that while she likes Leavitt’s mural, specifically, she is concerned about enabling billboards.

This is about the freedom to display art, though, says Betsy Sanz, an attorney for the libertarian Institute for Justice, the firm representing Mr. Young. “Art is expression that is protected.”

“Under the First Amendment, a government can’t regulate content,” says Ms. Sanz. “We don’t think that five people on the zoning board are the ultimate arbiters of art and expression.”

To Mr. Hounsell, a 12th-generation New Hampshire native, this town debate over what qualifies as an art is a uniquely New Hampshire, uniquely American story about self-determination.

“This is how you do it, this is how you live free,” he says, invoking the state’s motto. “You confront the issue of the day from an honest, transparent position and you welcome the debate. And it’s not about agreement, it’s about engagement. The more we can talk, the better we’ll see a way clear to do the right thing.”

“This is how government works. Being an American is an action verb,” he says. “You can’t be free if you can’t govern yourself.”