Can art help unite a diverse society? Museums aim to find out.

Loading...

| New York

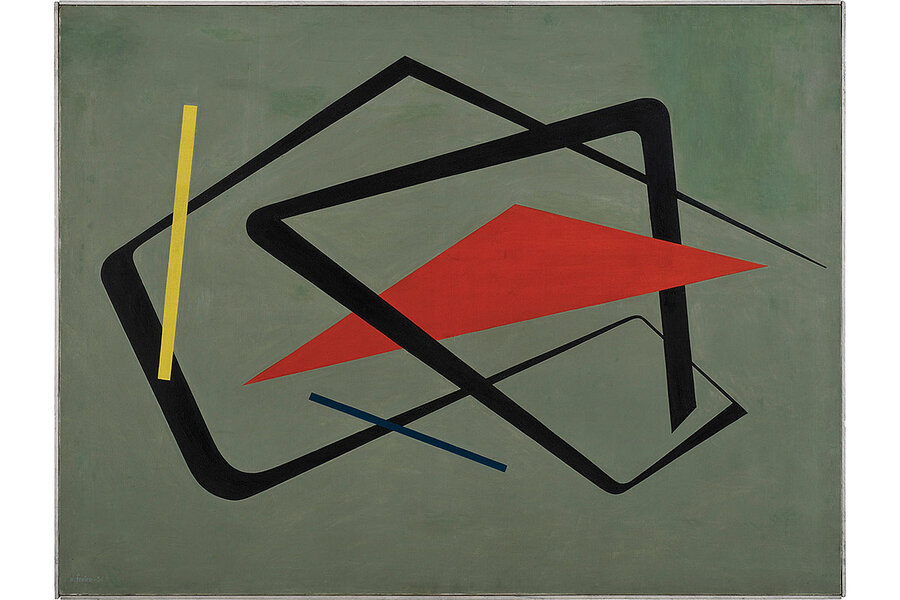

When the Museum of Modern Art in New York reopens Oct. 21, its revamped and expanded gallery space will reflect something that’s trending in museums across the United States: a focus on those less heard from.

A shake-up of art history is happening, and MoMA is emblematic of this revision. The early narrative of modern art focused on white male “geniuses” mostly from Paris and New York. The MoMA 2.0 version will be, according to chief curator of painting and sculpture Ann Temkin, “not a single narrative of one history” but more “a collection of short stories rather than one continuous novel.” She adds, “It feels like a real change, part of a much larger shift that has been going on in art history academically and in museums.”

The presentation of MoMA’s permanent collection and of temporary exhibitions promises to be wide-ranging, including art by women and artists of color who were overlooked. The shift is part of efforts by museums all over the country to embrace diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Why We Wrote This

How can the art on a museum’s walls better reflect the community it serves? A rethinking among U.S. museums suggests a shift is taking place that could reshape whose work gets shown.

“It’s like a sleeping giant awakened,” says Gregory Stevens, director of Seton Hall University’s Institute of Museum Ethics in South Orange, New Jersey. “Museums will never be the same.” He notes their prior role was to conserve the cultural legacy, but today, “Museums need to be here in the present, sharing important ideas, information, and inspiration about the world we live in.”

Independent curator Lowery Stokes Sims, who has served on the curatorial staffs of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Studio Museum of Harlem, and the Museum of Arts and Design in New York, remembers that when she started her career, “We used to joke the curator’s first job was to make sure [visitors] had shoes on and didn’t touch the art.” The priority today, as Monique Davis, managing director of the Center for Art & Public Exchange at the Mississippi Museum of Art in Jackson, says, “is to connect the power of art to the power of people.” That entails mounting exhibitions composed of not just “pretty pictures on the wall,” she says, but programs that “build bridges of empathy” by reflecting concerns relevant to the community.

This initiative, percolating for decades, reached a boiling point in the last few years. It became a critical issue after the Black Lives Matter movement spotlighted racial injustice and in response to social issues like immigration, LGBTQ rights, and gender equality. “Most art museums have been dominated by a white, male, Colonial perspective,” Professor Stevens says, “so the art displayed and interpreted has been seen through a very narrow lens.”

Ms. Stokes Sims, who is African American, is blunt: “The canon today is totally irrelevant, patriarchal, and racist.” Which makes broadening it all the more urgent. As one sign of change, for the first time in 70 years Columbia University is reforming its core-curriculum course in art humanities, which taught Western art to all first-year students.

The current state of political polarization spurred the update, according to Noam Elcott, chair of art humanities and head of Columbia’s committee to overhaul the syllabus. He says that the more open embrace of white supremacy “called for a reckoning,” adding, “An all-male, all-white curriculum ceased to be viable.”

In Charlottesville, Virginia, where white supremacists staged a 2017 march that ended with the murder of a counterprotester, the University of Virginia’s Fralin Museum of Art has resolved to devote half of its exhibitions to underrepresented art. “It’s important to make a real, discernible commitment,” says museum director Matthew McLendon. “There are difficult conversations our society needs to have. Mediation through the work of art, being respectful of cultures and experiences other than our own, adds a different tenor and a return of civility to the conversation.”

The Baltimore Museum of Art is a pioneer in community outreach. An initiative called “2020 Vision” replaces past myopia toward women artists with an entire year of exhibitions devoted to them. According to director Christopher Bedford, the museum’s holistic approach will “imbue the institution with a different lifeblood.” The contemporary wing now features works by artists of color “to establish a different canon that directly relates to the city of Baltimore,” he says. “As a cultural institution we’re attempting to move into social service and actually help people.” Mr. Bedford admits, “I’m not sure art changes lives. People do. But I think art changes people.”

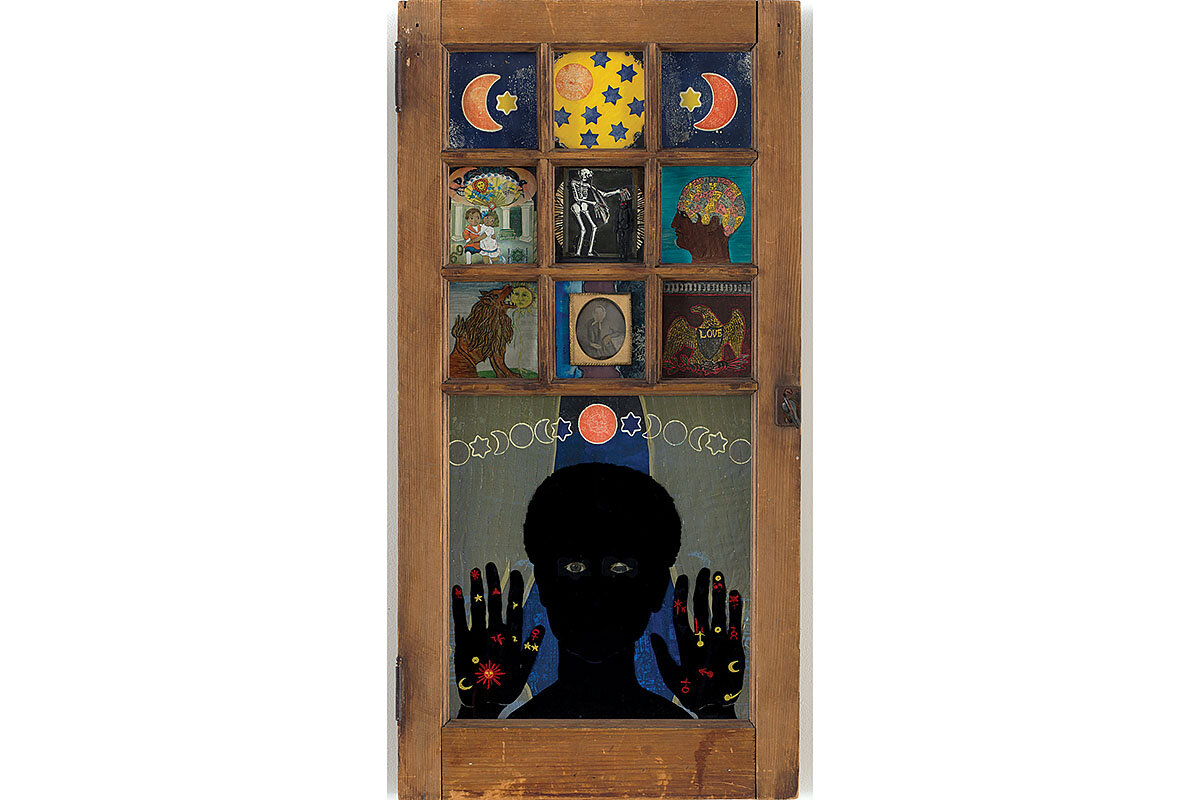

African American artist Oletha DeVane, called “the matriarch of the Baltimore art scene,” whose installation “Traces of the Spirit” is on view at the Baltimore museum until Oct. 20, says she sees artists as visionaries and teachers who, by sharing their stories, can increase understanding in our pluralistic society.

For Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, the thrust toward diversity and inclusion is not only a social necessity but also a savvy business move for institutions’ sustainability. More importantly, Mr. Walker terms museums “the most important institutions in our democracy.”

“We need to be reminded of who we are,” he says. “Today, more than ever, we need museums to reflect and mobilize the idea of our identity as a people, to bring us together and remind us of what’s unique about us and what we have in common.”

At this point, the concept of museums as paragons of inclusion and diversity is more aspirational than actual. Recent studies have documented a dismally low number of acquisitions and exhibitions of art by women and people of color at the top 30 art museums over the last decade.

There’s a long way to go, and whether the pace will dawdle or accelerate is unknown.

Ms. Stokes Sims says she is gratified to see “a new age dawning,” yet she is skeptical about the trend’s durability: “The canon is like a rubber band. You can stretch it, and it can always snap back.”