'Half the Sky' exhibition hopes to inspire action

Loading...

| Los Angeles

The folk saying “a hen cannot speak in front of a rooster" expresses a cultural bias that silences women’s voices in Burundi. An exhibition called “Women Hold Up Half the Sky” at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles until May 20 profiles a 36-year-old mother of six, Goretti Nyabenda, who was powerless in her family, saying, “I had no voice.” Defying her husband, determined to escape his beatings, Goretti joined a solidarity group sponsored by the aid organization CARE. After she received a $2 loan, she built a thriving banana-beer business.

“Now I know I have good ideas,” Goretti (who has become a community leader) crows, “and I tell people what I think.”

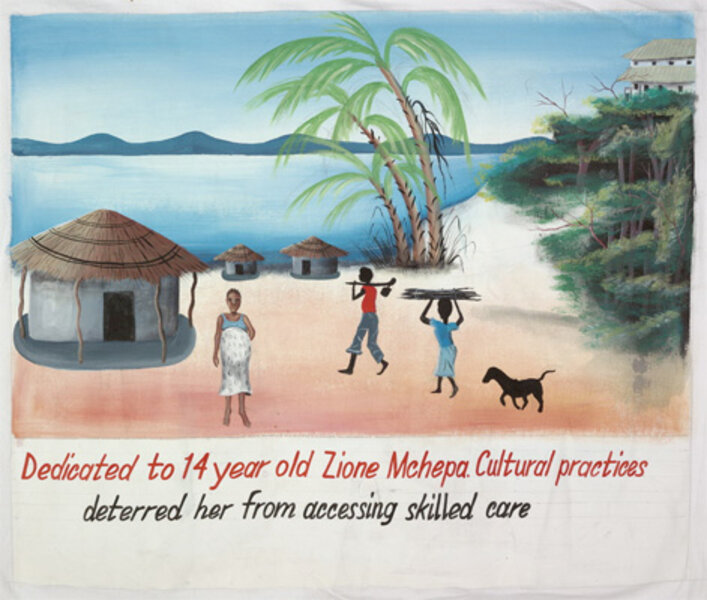

The title of the exhibition comes from a Chinese proverb "Women hold up half the sky." The exhibit is based on the bestselling book by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn, "Half the Sky: Turning Oppression Into Opportunity for Women Worldwide." Both book and exhibition focus on negative realities (trafficking, gender-based violence, and maternal mortality) and how empowering women through education and bringing them into the labor force provides positive gains.

It’s an exhibition with a mission. “It was a challenge,” according to consulting curator Karina White, “to take these really overwhelming and devastating issues and think about how to present them to inspire people to action.”

Skirball Museum director Robert Kirschner calls the show “not really an art exhibition. It’s not a collection of artifacts. It’s about ideas. It’s really about social conscience and focusing on certain issues and engaging a broad community.”

Turning a book dense with horrifying statistics (like the statement that more girls are killed in “routine ‘gendercide’ in any one decade than people were slaughtered in all the genocides of the 20th century”) into a visual experience was a daunting task. “How to make an exhibition without making it exhibitionistic?” Mr. Kirschner poses the dilemma.

The Skirball, dedicated to promoting a pluralistic society in which all are accorded dignity, is not a human rights organization. For the exhibition, the Jewish cultural center partnered with advocacy groups and nongovernmental organizations with expertise in the area.

The advisory committee stressed the danger of appearing paternalistic, even if well-intentioned, if the show featured social injustice in less privileged nations without highlighting local women’s leadership in setting an example of courage. More than statistics of atrocities, the show spotlights individuals who transform lives through activism.

“My primary goal was to inspire visitors to be moved and to take action,” Ms. White says. She balances emotional impact – like a wall of silhouetted women waiting to tell their stories of mass rape in the Congo – with images and text showing change is occurring. The West African group Tostan, for example, has educated women to end the centuries-old tradition of female genital cutting in 5,000 villages in Senegal.

White also commissioned new artworks to illustrate the themes, like sound recordings by artist Ben Rubin of local women trafficked and held in domestic slavery or forced into prostitution. (An estimated 10,000 women are held in Los Angeles underground brothels, according to immigration agents, and thousands are forced into labor without pay or hope of escape.) Survivors tell their stories, like a 33-year-old Kenyan woman who finally escaped to a shelter, saying in a soft, halting voice: “All we have to do is be strong.”

A lobby installation features the well-known Los Angeles artist Kim Abeles’s “Pearls of Wisdom: End the Violence.” During a two-year community-engagement collaboration, Ms. Abeles worked with domestic-violence survivors in shelters, producing 800 pearlescent sculptures, a small sample of which are shown.

The project serves as a metaphor for the exhibition, since abused women turned their trauma into objects of beauty and hope. Each began with a symbol of abuse, encircled by yarn, strips of bandages, plaster, and paint. “I realize the power and strength women have, but you also can’t ignore the challenges worldwide,” Abeles says. Calling those who escape domestic violence “champions,” she adds, “I’m not hot on the idea of thinking of women as just victims.” Each woman offers advice, ranging from the practical: “Always keep spare keys,” to the urgent, “If he wants you to be perfect, run ... run now!”

“It was important to pair with domestic violence here in our own community,” White notes, and to give voice and visibility to local struggles.

The design of the exhibition catalyzes visitors to express reactions. A cloudlike “Wish Canopy,” designed by the Los Angeles architecture firm Layer, overarches the exhibit floor. Composed of interlocking ovoid spaces, the canopy is gradually filling with viewers’ wishes for other women written on pink, lavender, and blue paper.

“The overhead canopy,” Kirschner says, “has turned out to be an effective, dramatic way to symbolize the power of collective action.” Some of the scrawled wishes are poignant, like “When I see violence, I will tell someone. I will not look the other way again” or “I wish you could see you are not alone.”

The exhibit’s most atypical aspect is the chance to take direct action to advance human rights. One kiosk offers a choice of recipients to receive a microloan, reinforcing one of the main messages: Economic empowerment of women improves lives.

An example is a case study of Saima Muhammed, a woman chronically hungry and assaulted by her husband before she turned a $65 loan into a prosperous embroidery business. Saima now employs 30 families in her village near Lahore, Pakistan, proving capitalism more efficacious than charity. She plans to send her three daughters to college. One daughter, Javaria, is a straight-A student, and hers is the smiling face on the exhibit’s poster.

Visitors can also sign petitions and send postcards to Congress urging legislative action. “We debated, as a cultural institution, whether we should get into that realm and decided, this is how things change in a democratic society,” Kirschner says. “Every human being has the right to be treated with respect and dignity and should be free of violence and have the opportunity for fundamental health care and education. If those things are partisan, then we’re partisan.”

In a telephone interview, Mr. Kristof said it was “exhilarating to see some of these extraordinary women whom I so admire getting a spotlight on them and their work.” Asked why ensuring basic human rights for women is not a global policy priority, he answered, “Probably because it’s just the way things have always been, so it’s not really news. There’s no one day on which women are particularly abused more than others. It’s just the backdrop of humanity.”

After researching these issues for 20 years (first with his wife, Sheryl WuDunn, as New York Times’ China correspondents and now as a Times columnist), Kristof sees enormous progress. “It’s not just humanitarians who are pushing to get girls in school. It’s also American generals in Afghanistan. That’s very powerful, when everybody realizes the way to bring about change in a country is often to educate girls and bring them into the formal labor force.”

The message is that school – not military – uniforms, and books – not bullets – are the way to go. For peace and stability in the developing world, microloans should replace maxi-bombs. The movement is gaining traction “not just because of our book. We were pushing on an open door,” Kristof says. “There’s an increasing realization that if you want to change the world, investing in women and empowering women offer tremendous leverage to accomplish that,” he adds.

More than just showing pretty pictures, the Skirball Museum’s goal is to change the world. As White says, “It’s hard to get much more important than this.”

To enhance its outreach, plans are in the works for the exhibition to travel nationally and internationally. In addition, a two-part prime-time special will air on PBS in early October. “The aim is to reach people,” Kristof affirms. “What we want to do is not just inform people but to really make a difference.” He adds, “There are no silver bullets,” but educating and empowering women are “about as close as one can get. It really has an impact.”