Hollywood writers got their deal. What happens next?

Loading...

The story of the writers strike had a dramatic first act, an overly long and stressful middle, and a triumphant ending for the union. No one is clamoring for a sequel.

Rob LaZebnik, a veteran writer on “The Simpsons,” heard the news Sunday night. His ebullient mood is akin to the show’s opening sequence, when the animated clouds part to reveal a blue sky.

“It’s just made everybody feel like, ‘Wow, this time it really worked,’” says Mr. LaZebnik, who has participated in several writers strikes during his decadeslong career. “Everyone felt doubly passionate about the issues. It was so obvious to us that there were all these inequities, that it really pulled everybody together.”

Why We Wrote This

The Writers Guild of America is the latest union to score big wins in 2023. But with Hollywood in flux, will writers be able to hold on to a middle-class life long term?

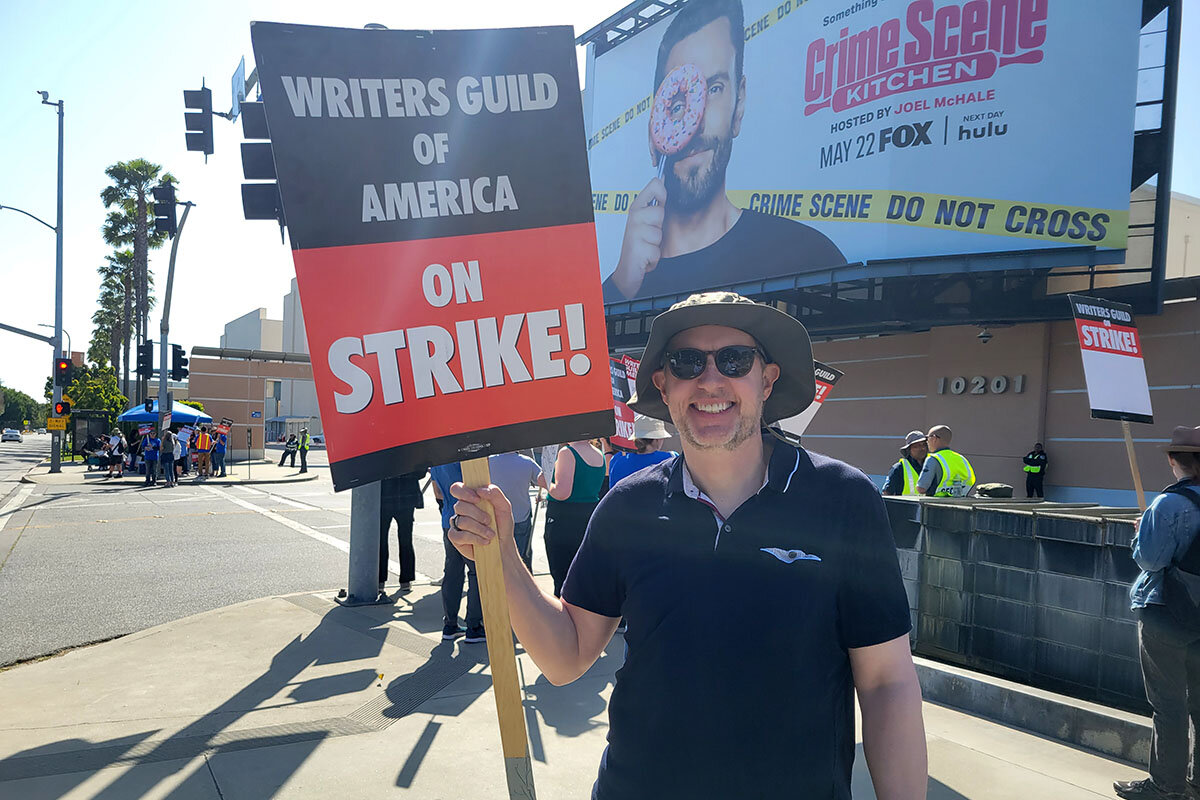

After 146 days – the second-longest strike in its history – the Writers Guild of America won concessions on every major issue, including mandatory staffing levels on series, increased residual payments for streaming, and protections against artificial intelligence. While precise details have yet to emerge, if the tentative agreement the studios and the WGA agreed to late Sunday holds, it would be yet another win for organized labor in 2023.

In a statement to guild members, the negotiating committee touted the deal as “exceptional.”

But after a hard-fought battle that cost California alone an estimated $5 billion, Hollywood remains an industry in flux. The proposed contract would install protections that writers say are vital for maintaining a middle-class life, rather than being reduced to gig workers who get paid for a month or two at a time. Will those protections remain beyond the length of a new three-year contract? Or will Hollywood’s TV and film writers ultimately be facing a freelance future?

“Whether creative people in Hollywood ultimately have more stable and rewarding careers is really going to depend on whether entertainment companies can make their streaming services more profitable,” says Ben Fritz, author of “The Big Picture: The Fight for the Future of Movies,” via email.

One deal down, one to go

The studios and streaming services, which are represented by the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, issued a press release consisting of a single sentence: “The WGA and AMPTP have reached a tentative agreement.” Some observers believe that the reason the studios aren’t celebrating, at least not outwardly, is because the strike has come at a great cost. Plus, the AMPTP still has to reach an agreement with the 160,000 members of the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA). Most Hollywood productions won’t be back in business until the actors resume work. But viewers can expect to see late-night and daytime talk shows back on air soon.

“The studios and streamers, along with the writers, were starting to fear if they didn’t get a deal done soon, it could drag out until the end of the year and destroy all of this year’s television season, as well as next year’s movie slate,” says Mr. Fritz. “So they were very motivated to get a deal done.”

First, though, WGA members will need to vote on the deal. It’s widely expected to pass. The negotiating committee told writers that it’s made “meaningful gains and protections for writers in every sector of the membership.” Its statement also praised the picketers for standing shoulder to shoulder, picket sign to picket sign, during the nearly five-month work outage.

“An underreported thing is that there were some amazing speeches, talks, more like fireside chats, especially from Chris Keyser ... one of the co-lead negotiators,” says Mr. LaZebnik. “That kind of reverberated throughout the whole strike.”

The WGA received significant support from SAG-AFTRA, as well as unions such as the Teamsters and International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, who refused to cross picket lines. Many companies and individuals donated food and money to the strikers.

“It’s a huge moment for the labor movement in America,” says Zayd Dorhn, Chicago captain of the WGA and director of the Master of Fine Arts in Writing for the Screen and Stage at Northwestern University. “The corporate CEOs and Wall Street investors have to take seriously now the fact that workers are united and having a moment where they’re not interested in small deals or in watching more record Wall Street profits. They’re demanding their fair share.”

The writers enjoyed a high level of approval among Americans, a survey from Gallup found last month. Some 72% of respondents supported the WGA, compared with 67% overall who support organized labor. That’s up from a low of 48% in 2009, although down from last year’s 71%. (The studios, meanwhile, garnered 19% support from the public.)

What next for the actors?

It’s hard to predict what the end of the writers’ strike portends for the SAG-AFTRA negotiations. The actors may feel pressure to resolve negotiations so that production can resume. Or they may feel emboldened to stick it out, as the writers did, in the hopes of a better-than-expected deal. One issue that the writers and actors shared in common was a call to place guardrails on the use of artificial intelligence in productions. While details are not yet known, the agreement between the WGA and AMPTP on artificial intelligence may smooth the way for a pact between actors and the AMPTP.

The entertainment companies made concessions to writers on issues that they’d seemingly been unwilling to budge on. Writers had asked for increases in royalty payments – known as residuals – for popular movies and series on streaming platforms. But that would require the studios and digital platforms to be transparent about how TV shows and films perform. It’s not yet clear how the new arrangement will work when it comes to sharing data. The WGA had also pushed back on the common practice of hiring a small number of writers to initially develop a show. It had demanded hiring a minimum number of scribes for series.

If ratified, the deal between the WGA and the AMPTP will be good for three years. In 2026, the two sides will sit down once again to evaluate contract terms. During the interim, Hollywood studios and streaming platforms will remain under pressure to fix their business models. Among the issues: Viewership for broadcast television is dwindling. Customers are cutting the cord on cable. Many expensive blockbusters, such as the latest “Indiana Jones” and “Mission: Impossible” movies, haven’t performed well at the box office. Even before the strikes, Hollywood had begun a period of contraction with thousands of layoffs. The studios were able to use the strike to cancel some deals and productions under force majeure rules.

With the exception of Netflix, the streaming platforms have yet to turn a profit. For now, digital platforms have been able to sustain losses because parent corporations such as Amazon, Apple, and The Walt Disney Co. have other sources of revenue outside of TV and film. But unless streaming services get out of the red, there will be a smaller pie to share with writers.

“We have knitted these life vests together over the course of this strike,” says script consultant Tom Nunan, a former TV executive and producer of the Oscar-winning film “Crash.” “But we’re still on the verge of going over the falls. You know, we will probably survive it with these life vests, but the future is very uncertain.”

Mr. LaZebnik, the co-executive producer on the “The Simpsons,” is concerned that studios could potentially pull back on the number of shows that they order. But he believes that the success or failure of the strike was nothing less than an existential moment for the WGA and his profession.

During the long months, he maintained a text thread with “Simpsons” scribes in which they shared silly jokes. “It was sort of an outlet for some pent-up comedy,” says the writer. “Obviously, we would never have wished this on anyone to strike. But at the same time, you can’t help but just come back from almost five months off feeling like we are a little rejuvenated.”