From fig leaves to ‘French Connection,’ the impulse to sanitize culture

Loading...

| New York

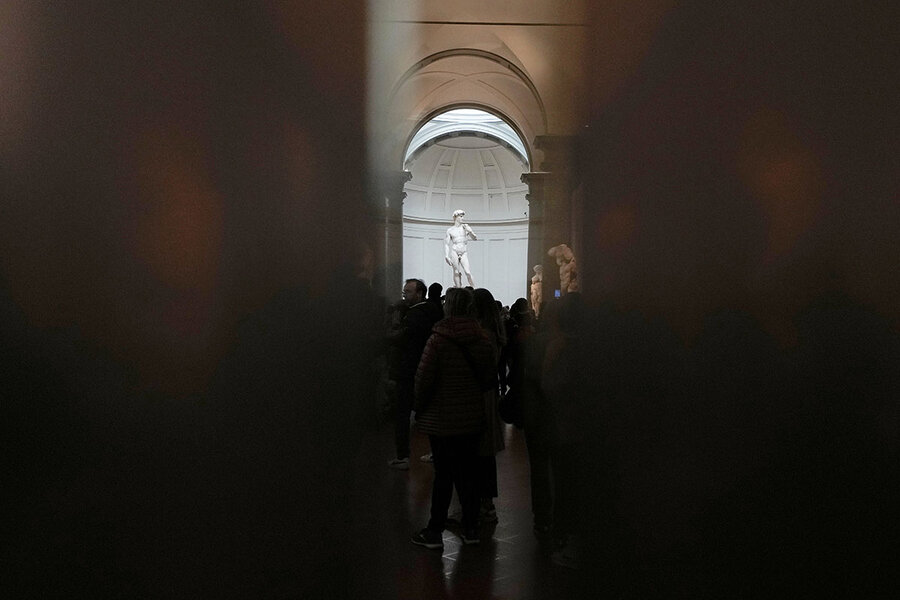

The tradition to alter or otherwise censor certain artistic productions goes back centuries.

The reasons can vary, but from fig leaves on sculptures to TV versions of classic films, when a work of art has a wider and more varied audience, censors work to cover, replace, or reshape the originals to make it more publicly palatable.

Over 200 years ago, the English physician Thomas Bowdler and his sister Henrietta edited the works of Shakespeare, removing anything that could be considered blasphemous or sexual – providing a “family” Shakespeare that could be read aloud with children and women present. Their efforts added a new pejorative to the English language: to bowdlerize.

Why We Wrote This

Whenever efforts to sanitize the works of the past arise, like now, scholars say those arguments are really about the future – and who gets to decide what’s possible.

Unlike banning or full censoring, bowdlerizing certain works of art can include a positive intention. There’s a recognition of a production’s value and a desire to increase its audience, not shut it off. At the same time, however, like full censoring, removing offending scenes or language represents a kind of social control over audiences, a maintaining of the status quo.

“The debates we’re seeing around censorship, adaptation, editing classic works, or however you’re going to frame it, isn’t new,” says Tobin Shearer, professor of history and director of African American studies at the University of Montana in Missoula. “We have returned to these things repeatedly as a nation. They are touchstones for recurrent struggles that always surround religion, sex, violence, social boundaries.

“And I think, as an interpreter of the past, these struggles are always much more about the future,” he continues. “What are the possibilities of imagining what is yet to come? Who gets to decide that? These questions are baked into these recurring debates.”

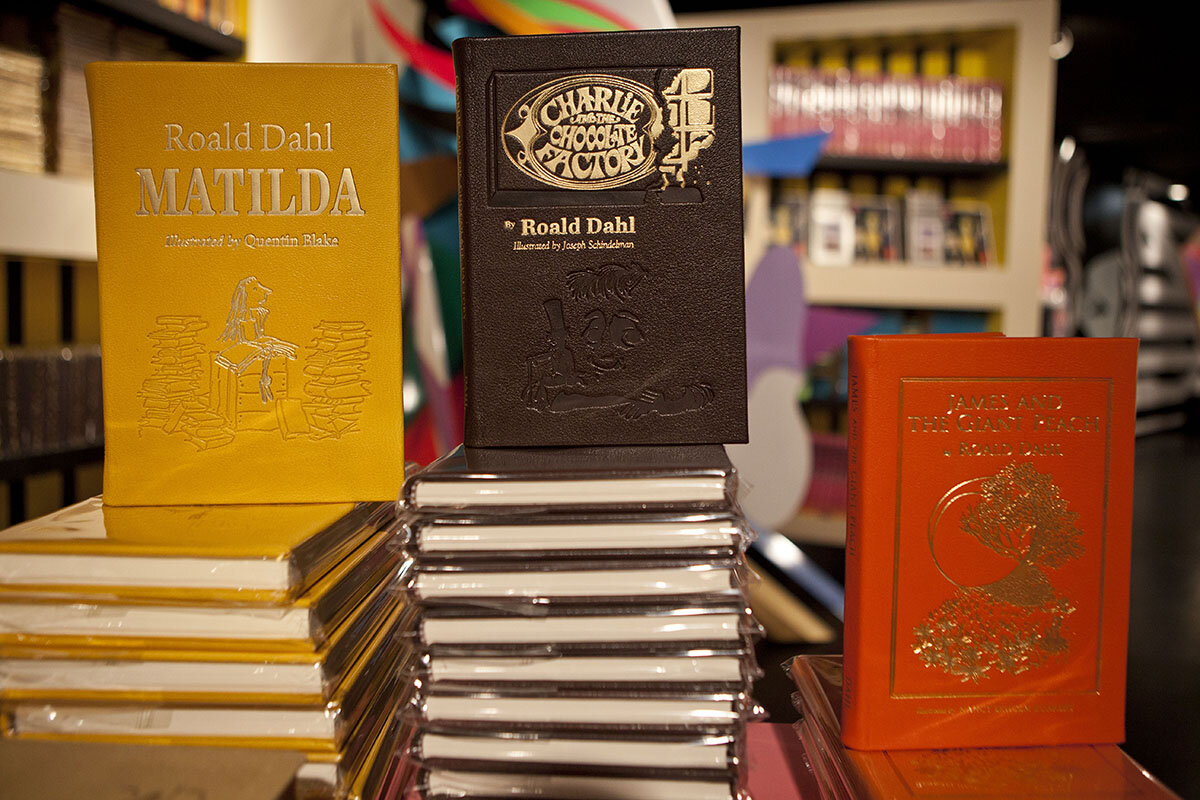

Earlier this year, publishers cleaned up language from the children’s books of Roald Dahl and the mysteries of Agatha Christie, removing potentially offensive language about body types or ethnicity. After a widespread backlash, Penguin announced it would keep the original version of Dahl’s books for sale as well. This year marks the 70th anniversary of the first James Bond novel by Ian Fleming; the publisher announced it would reissue his novels after scrubbing them of outdated references and racist language.

A number of streaming services in the United States this summer removed a scene that contained racial slurs in “The French Connection,” a 1971 film that won the Academy Award for Best Picture and influenced the gritty style of films that came to define the 1970s.

“There’s a real moral panic happening within both the left and the right about what people are capable of understanding and tolerating and learning from,” says Bill Yousman, professor of communication and media studies at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut. “My reaction to the ‘French Connection’ changes was, okay, let’s not have this fictionalized cop use the N-word, because then that means that police never use racial slurs? And now I can feel better; I can go to sleep with the notion that, well, there is no racism in doing police work, and, no, they don’t talk like this?

“It’s a real dismissal, I think, of the audience, or that belief that people are capable of understanding what a film or book is trying to convey, the larger social context in which it was originally written, and what it’s trying to say about society,” he says.

Han shot first

Earlier this year, director Steven Spielberg said he made a mistake when he altered his 1982 film “E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial” in the early 2000s. He had been concerned about a scene in which armed federal agents approached children in the film with their firearms drawn, so he altered the scene with the agents carrying walkie-talkies instead.

“I should have never done that because E.T. is a product of its era,” he said during a panel discussion at the Time100 Summit in April. “No film should be revised based on the lenses we now are either voluntarily or being forced to adhere to,” he said, saying the original versions of classic films should be considered “sacrosanct.”

In the original “Star Wars,” it was the character of Han Solo who was altered, even as new scenes were added as technology improved. In a famous scene at the Mos Eisley cantina, the original shows the swashbuckling character preemptively shoot a bounty hunter under the table. In the altered version, Han Solo shoots only after the bounty hunter, Greedo, draws first.

“It’s easy to make fun of these things, and I do sometimes, but I do think that there’s something troubling about it,” says Professor Yousman. “There’s a certain level of censorship that’s coming, I think it’s fair to say, from all sides of the political spectrum now.”

Another approach

Instead of altering content that could be considered problematic, the Walt Disney Co. issues a warning message at the start of some of its classic animated films, including “Dumbo,” “The Jungle Book,” and “Peter Pan.”

“This program includes negative depictions and/or mistreatment of people or cultures,” the initial warning reads. “These stereotypes were wrong then and are wrong now. Rather than remove this content, we want to acknowledge its harmful impact, learn from it and spark conversation to create a more inclusive future together. Disney is committed to creating stories with inspirational and aspirational themes that reflect the rich diversity of the human experience around the globe.”

The motives for editing out offensive language and scenes from certain works are understandable, says Paul Levinson, professor of communication and media studies at Fordham University in New York. “No decent person wants to be entertained with racial slurs and insults,” he says, “and we’re doing our best to extirpate words like that from public society.

“But I think still that the safest and best thing to do in terms of the well-being of a free democratic society is to leave these works alone,” he continues. “You can make a decision about whether a work is age-appropriate, but when you start changing works to make them more suitable, it’s just as easy to start banning books – and that’s not to protect anyone. That’s to demonize certain people so that kids will have no knowledge of them.”

Indeed, sanitizing the past only tends to foreclose the possibilities of the future, says Professor Shearer at the University of Montana.

“I’m a progressive, but I get very uncomfortable with the efforts to censor past historical documents because I think it’s a matter of equipping our youth or others – I want them to confront that past and to know exactly what it looked like. I don’t want to pre-screen it for them,” he says.

“On the one side,” he adds, “you can see with the book-banning efforts in so many states a sense that we don’t want our youth to really be able to engage with ideas that might make them think alternative thoughts – thoughts that could rearrange the way we do relationships, or that could rearrange the way we shape our political environment.”