Moral support: How we raise a ‘good person’ in fractured times.

Loading...

| Haverford, Pa.

Here at the playground, the rules are clear: Be nice. Don’t hit. Take turns.

But if the rules are clear here, they get hazier as life progresses.

The standards of moral integrity prevailing since ancient times – and until recently passed along in sanctuaries and Sunday schools, Scout meetings, history lessons, fairy tales, and traditional “great books” – have undergone a sea change in the past 10 years. As religious attendance plummeted, the Western canon itself came under attack, and an extreme political divide undermined what common ground remained.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onWhere tradition once conveyed established virtues and vices, moral integrity is now transmitted via a font of input, from school and sports to social media and friends. Parents improvise to teach “how to be good.”

As a result, “The moral and spiritual canopy under which life was lived is gone,” says Robert Wilken, professor emeritus of the history of Christianity at the University of Virginia.

Where tradition once conveyed established virtues and vices, today’s culture is a bottomless font of input, from school, sports, and social media, to celebrities, politicians, and friends. One person’s villains are another’s heroes, and vice versa, with no clear agreement on right and wrong.

And while remnants of a traditional moral framework remain, parents are picking and choosing which ideas to pass on – and in what context. Morals thus have become even more than ever a matter of individual preference and less a matter of societal norm.

The new morals options couldn’t have been clearer than during interviews with two parents approached at random one sweltering summer morning at Freedom Playground in suburban Philadelphia.

Alex Brophy describes his family’s target values as centered on diversity. He tries to avoid pitfalls like ableism and gender stereotyping, he says: “I want my kids to appreciate people from different backgrounds.”

Fellow playground parent Liz Boring says hospitality is a key virtue under development in her family, as they focus on tone of voice and word choice: “We’re working towards greeting others and speaking with them with words of welcome.”

The two chatted separately with the Monitor about the goals for their children. They share one community, one park, one school district, and even the same childhood religion. But they illustrate very different visions for rearing moral children.

Morally calculated decisions

Mr. Brophy, who with his wife is an immigration attorney specializing in LGBTQ clients, described his approach as “child-led,” with his role as helping his children make good choices.

He does not currently practice religion and disagrees with the Catholic Church of his childhood on many social issues, but he explains that much of its moral framework remains. “What I took from my understanding of Jesus is ‘Love your neighbor, even if you believe your neighbor is doing the wrong thing.’”

His aims for his children, ages 10 and 6: to teach them “to be kind to others ... and to help them have the understanding that life is complex, that society is complex, and to appreciate our differences.” Heavily focused on issues of gender, ableism, and climate, Mr. Brophy is a self-described progressive, and is vice chair of his local Democratic Party.

His children attend public school.

“It was very refreshing,” he says, to learn of this school’s advocacy of values like empathy, respect, tolerance, and kindness, a far cry from the “Lord of the Flies”-like atmosphere of his own childhood public school. Careful with his use of gender pronouns, he likes the school’s attention to such issues, and appreciated the parent workshop that was held to express support for his 6-year-old daughter’s transgender classmate.

Mr. Brophy’s day-to-day moral priorities also center on environmental questions – driving versus walking for 15 minutes; whether a summer heat spike merited his use of air conditioning; whether his recycling a jar without cleaning out its contents could be forgiven on occasion.

He’d like to see his children make good moral calculations of their own.

“I want my kids to be cognizant that the decisions they make for themselves have an effect on others. I want them to consider that they are not alone, that what they want affects others.”

Focused on the virtue of patience

Ms. Boring, a fundraising professional who was expecting her fourth child and was at home full time last summer, describes her approach as “very intentional” and her family as strongly Catholic in what she described as an orthodox way.

“Our faith is the bedrock of our life,” she says. She and her husband, a Marine officer now in the reserves, together set the goals for their children’s moral development. “We want to equip our kids to be happy, healthy, and holy,” she says.

Over the summer, the family’s goals for their children, ages 9, 6, and 3, were threefold. In addition to the hospitality, she says, they are focused on the virtue of patience, on “speech, tone of voice, self-awareness of feelings and frustrations, and self-control.” Finally, she says, they practice taking breaks from activity “to process feelings, to pray, to calm down hearts and minds.”

The family chose a classic Catholic academy whose virtues-based curriculum reinforces the virtues approach at home.

“I love that the school is giving them a language for some of these things,” explains Ms. Boring. “I think that the question that the culture poses to us most is ‘you are deciding who you want to be’ as opposed to, ‘this is the ideal that we aspire to as people of God, as humans; that there are standards; that there are ideals that are built into the nature of creation that we are working towards.’”

She acknowledges the family’s approach is not popular. They find reinforcement through association with like-minded families, but she explains that insularity is not their goal. “We’re not simply trying to find our tribe and stick to it. We are trying to find a tribe to be strengthened and supported by, and then to continue to live in the world. We have a duty to live in the world.”

Ad hoc versus traditional morals

History will reveal the past decade to have been “as transformational as the 1960s” in terms of social and moral change, suggests Lydia Saad director of U.S. social research at Gallup Inc.

The percentage of adults who identify with a specific religion continues its heavily reported decline, especially among young people, according to Gallup. Religious people are less likely – in some cases far less likely – than others to tolerate certain behaviors relating to sexual morality, such as teen sex, pornography, and same-sex relations. They also are less likely to tolerate certain behaviors involving ending human life, such as abortion and doctor-assisted suicide.

Attendance at worship services – where religiously based values are likely to be imparted, Ms. Saad says – has plummeted: 37% of adults reported in 2011 attending in the last seven days and 29% reported attending in person or virtually in 2021. This trend, coupled with the declining religiosity in young people, suggests that religion-based morality will be replaced even more rapidly in the coming years by a humanistic, live-and-let-live perspective, she says.

The rapid decline of the traditional moral canopy, Professor Wilken says, leaves no system or structure for moral discernment as a replacement. Instead, he says, there is improvised moral reasoning: “What seems immediately logical [is what] people are willing to act upon.”

Some of the ad hoc morality draws on concepts similar to the traditional. The golden rule remains a rudder for many, as do remnants of an established Protestant worldview.

Some organizations offer their own sets of values. The “Ten Commitments” offered by the American Humanist Association share common ground with religious tradition, says Kristin Wintermute, director of education for the group, whose members believe “you can be good without a God.”

Richard Flory, executive director of the Center for Religion and Civic Culture at the University of Southern California, says his 2020 study of young adults reveals a generation unable to articulate their religious and spiritual beliefs. Instead, they practice a do-it-yourself morality, with decisions based largely on feelings, not reason.

The study reveals a loose set of seven commonly held tenets that describe the young adult worldview: karma is real, everybody goes to heaven, just do good, it’s all good, religion is easy, morals are self-

evident, and no regrets.

With less systemization than a formal moral code, the ideas are “more quickly morphing and developing,” lacking the power of a religious institution as both a carrier of the ideals and a provider of opportunities to live them out, reports Mr. Flory.

If things are “all good” in the young adult world, they seem anything but that in the schools. Perhaps nowhere is the furor over what qualifies as moral more intense than in public education. Here, according to Robert Pondiscio, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, only “anodyne values” – please, thank you, and the like – remain as universals. Here, too, the past decade has seen a sea change, from depoliticized values linked to performance – goals such as grit, perseverance, and punctuality – to a focus on nebulous “therapeutic” goals concerning beliefs, attitudes, and values.

He sees this as “mission creep.”

“It’s become so-called social and emotional learning, ... an overly broad and virtually meaningless descriptor for a lot of different kinds of ideas and behaviors and values.” Assigning roles more fitting for parents, counselors, clergy, or social workers to teachers untrained in the tasks being delegated to them saps time from the task of graduating literate 18-year-olds capable of work, college, or the military, he explains, and is an unprofessional substitute at that.

However, says Jay Greene, senior research fellow of education policy at The Heritage Foundation, the notion that America is coming apart at the seams is overblown.

“We didn’t always have national fora for arguing about our disagreements, but those disagreements have always been there,” he says. “Schools have always been charged with teaching values, but in the past they haven’t had to adjudicate national disagreements and values, just local ones.”

The same is true today, he says. But Cabinet-level directives and funding tied to national mandates inhibit the diverse solutions that local communities, with more independence, could create on their own. Decentralization reduces the intensity of conflict over values, he believes.

Of course some parents do choose to go elsewhere, and it’s not only to escape progressivism, as might be expected from the school board furor over library books and critical race theory. Some want more critical race theory, not less, Mr. Greene explains. And some consider their public schools too religious.

Ms. Wintermute reports that her association is considering developing a home schooling curriculum to serve the needs of humanists in the Bible Belt.

Of course, what, exactly, qualifies as “religious” is also up for grabs. Whether they substitute “good” or “justice” or another value for “God,” Mr. Greene believes, progressive reformers are “simply another religious sect – urging behavior on fellow citizens in as zealous a manner as religious sects in the past.”

The classical, virtues-based schooling option holds appeal for secular and religious parents alike, says Mr. Wilken. The Greek, Roman, and medieval thinkers, he says, “talked about the fundamental realities that govern human life, about the primacy of truth, goodness, and beauty.”

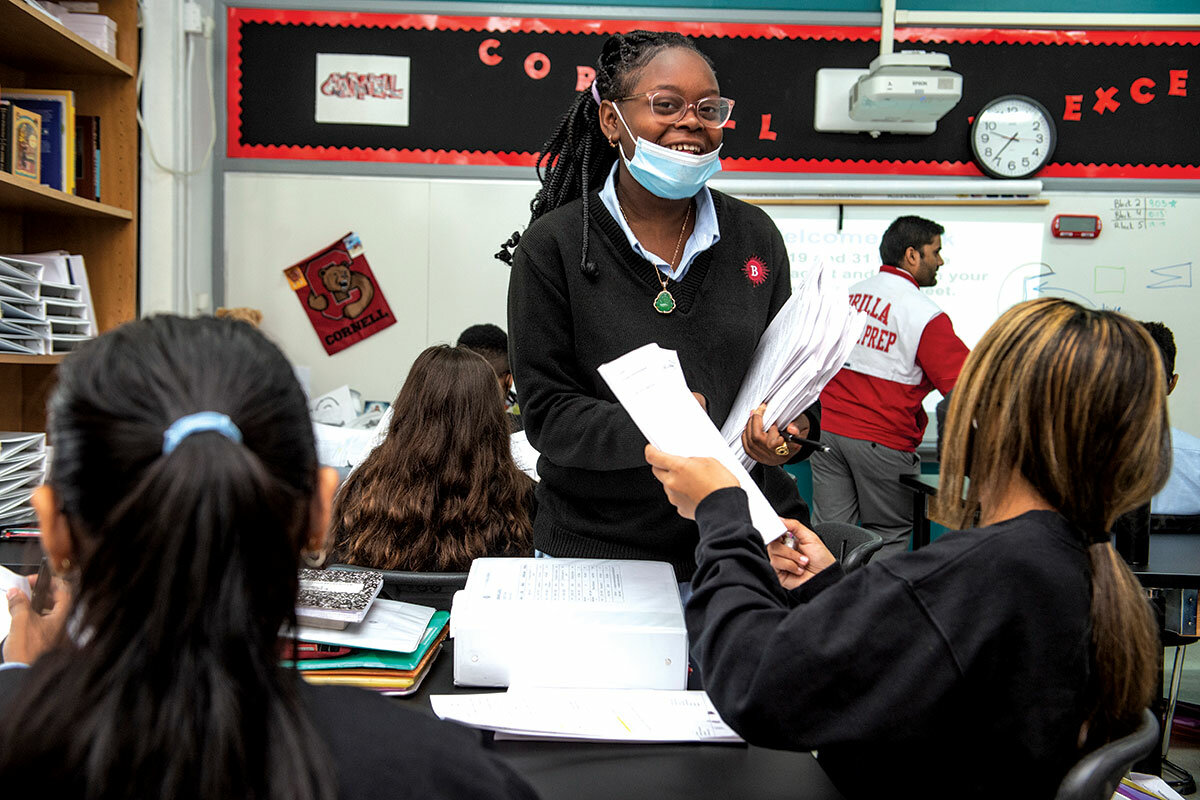

Like other classical networks, Brilla Public Charter Schools, a New York City virtues-based network, is expanding. It has 2,000 students – largely from Latino families – at six campuses in the Bronx, with new schools opening in Paterson, New Jersey, and Rio Grande Valley in Texas. Here the teachers themselves prepare by studying the ancients like Plato, and they broaden the traditional classical focus by including recent thinkers like Martin Luther King and W.E.B. Du Bois.

According to Stephanie Saroki De García, a Brilla director, many parents select Brilla because they oppose the sex education curriculum in New York’s public schools. “It creates a huge gulf between parents and their kids,” she says of the conflict.

The Brilla curriculum is guided by four core virtues – courage, wisdom, justice, and self-control. In sex ed, she explains, “We give kids the facts ... and then we ask them, ‘What is the most excellent choice you can make at this time?’”

The excellent choice, she says, is “one that respects your own dignity and that of others, and that leads to your flourishing.”

Some 800 of the Brilla students attend a Catholic after-school program founded by Ms. De García and run by Seton Education Partners, which manages the charter school network.

“We do such a disservice to children and families when we can’t include God in the mix,” she says, underscoring her decision to leave public education. She recalls feeling that her hands were tied during a secular Teach for America stint in Oakland, California, in the 1980s. “I think knowing that you have a father in heaven who loves you completely and will never abandon you is such a powerful gift to children.”

A vision of "good"

Even with school choice innovations, experts foresee most of the country’s students continuing to go to their assigned public schools. Meanwhile, all manner of camps, Sunday schools, study guides, curricula, seminars, and symposiums aim to buttress religiously linked morals in a popular culture that, at best, doesn’t understand them and, at worst, pushes against them.

Tamara Gray is director and chief spirituality officer at Rabata, an online education and spiritual resource for Muslim women. She aims to help young women, often immigrants, square their theological imperative of service to family – and the family imperative of service to neighbor and community – with an American culture that can often feel antagonistic to these values.

“The concept of service is possible without the concept of feeling trampled on,” she says. “We are all about embracing beauty in life and pushing back against all that is ugly.”

She aims her students toward a strong spiritual underpinning, which she believes leads them to find joy even in the mundane. “We’ve known people in history that seem to have this very clear self that is just so happy to be alive, no matter what is happening, and [they are] just really good to everyone around them. That’s the self we’re striving for.”

In a more secular vein, youth sports supplants the civic association of old in its role as community galvanizer for many parents. The values imparted largely depend on the subjective perspectives of volunteer coaches, says John Engh, executive director of the National Alliance for Youth Sports, which offers training to program administrators and volunteers.

His organization sees some 25 attributes emerging from youth sports programs “if done right.” Among them – learning to make friends, to win and lose with grace and dignity, to win with integrity, to wait your turn, to try harder if you want to play more, to develop a love for physical fitness – all finding a place in later life for the athletic and nonathletic alike. “I think those things that are inherent in the game are great because they’re not just sports things.”

Of course the outsize role of the internet raises the alarm for many parents. Whether TikTok proves to be the end of civilization as we know it, or just another in a history of parental fears and adaptations, remains to be seen.

Gallup’s Ms. Saad takes a wait-and-see attitude, citing concern in the 1950s over the assumed corrupting influence of comic books. “It strikes me as similar today to social media” – possibly a “nothing new under the sun piece of the story,” she posits.

And then there’s Hollywood, where traditional morality – religious and secular – is often the foil, an authoritarian establishment standing in the way of the righteous – or at least of the righteously rebellious.

“While it’s a badge of honor to be considered religious in some parts of the country, it’s sort of a badge of shame in other parts, and those parts where it’s a badge of shame tend to be media related,” says Diane Winston, Knight Chair in Media and Religion in the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California.

But that may be changing.

Streaming TV is allowing a fuller depiction of characters of faith, for instance, she observes: “I think shows where religion is just sort of applied helps people to learn what it means to live with faith.”

Also relatively new is what Dr. Winston describes as the “coming out” as religiously observant of some in the legacy news media, a business traditionally composed of nonreligious people. Some in the industry have signaled a need to broaden its definition of diversity by inviting openly religious staffers into the newsroom.

If stories from history and literature, fable and parable, Instagram and Netflix shape the societal task of rearing good adults, it’s the homegrown characters who will likely have the starring role, defining and prioritizing and interpreting what the next generation’s vision of “good” is. Theirs will be the stories told at bedtime and at the dinner table, at holidays and at summer reunions, stories that massage family legend and frame its actors in terms of right and wrong.

Among them, no doubt, will be the players at the local park. There will be the dad setting an example by substituting a 15-minute

walk for a 1-minute drive in order to spare the planet unnecessary debasement. There will be the mom who teaches her tot the finer points of greeting another, seeing in his future an adult who has the skills to graciously welcome a stranger.

Says Dr. Winston, “People live by story.”