As Americans fly the coop, county fairs spring back to life

Loading...

| San Diego

Perhaps one hasn’t truly reentered post-pandemic life – unmasked, undistanced, unconcerned – until one has seen a pig fly.

We’re in Del Mar, California, a couple of beach towns north of San Diego. It’s early in our national Summer of Reentry. Just recently, California became one of the last states to lift all COVID-19 protocols, though some cities, such as Los Angeles, have reimposed them. And now here we are in the coastal sunshine and sea breezes at the San Diego County Fair, one of the first mega-fairs on the 2021 U.S. calendar. To be sure, it’s not as “mega” as usual. But it’s “mega” enough for games and rides and magicians. For a Ferris wheel rising high over the endless Pacific. For carnival barkers and food stalls and wild-animal whisperers. For astonishments. For crowds.

And maybe most important, it’s big enough for those crowds to feel communal again – for each of us to rub shoulders heedlessly under a warm sky and rejoin life en masse.

Why We Wrote This

Americans are eager to resume the rites of summer passage. Boisterous parades, stock car races, zucchini festivals, and, yes, the iconic local fairs that are so much a part of American culture reveal a nation ready to revel in communal celebration and fried dough.

Finally, after a 2020 gone dark, the rites of American summer passage are back. The flag-draped parades, the annual festivals (from arts to music to zucchini), the ritual family gatherings. And, yes, the endless cycle of state and county fairs. Here in San Diego you can sense in people their relief and hunger and joy – their eagerness to convene again in traditional ways. To have a collective adventure, maybe.

And maybe to see some things you don’t see every day – even see some things that, let’s be honest, you didn’t think you ever would.

The pig in question is named Swifty – so called by Zach Johnson, proprietor and ringmaster of Swifty Swine Productions. For 23 years, Mr. Johnson and his extravaganza have done the “circuit”: county fairs, state fairs, rodeos, car races. “All 50 states except Alaska and Hawaii,” he says proudly. Then last year he went nowhere.

Now, standing outside the enormous apple-red trailer that houses pigs and people, he grins in that Southern California light that makes every hour golden hour, and says, “I do love to race pigs.”

Next thing, he’s flipping switches, tapping his headset mic to check sound, readying for the 1 p.m. show – of which Swifty and her flying act will be a part. First, friends, there will be racing.

Have you seen a pig race? (You don’t say.) In the next nine minutes, Mr. Johnson will introduce you. On this day, despite the afternoon having scarcely begun and the fair crowd still arriving, the grandstands are already filling up. At their foot is a small, short-fenced track, cushy with wood chips. Suddenly over the loudspeaker comes music and horn blasts you might hear at Churchill Downs. It’s time. “Should we bring ’em out?” Mr. Johnson asks. Indeed we should, says the crowd.

At which point Mr. Johnson knows he’s got you in the palm of his hand, because four tiny piglets come juddering down a ramp from the trailer and the entire audience involuntarily goes, “Awwww.” Mr. Johnson divides the watchers into four sections to back each pig, explains that the racers will run the track for the reward of an Oreo, and tells us our pigs’ names – which he’s repeated so often that he knows to the decibel how his listeners will respond. Meet “Kevin Bacon,” “Britney Spare-ribs,” “Brad Pig,” and “Kim Kardashing-ham.” And they’re off.

They’re fast, which is not the point. They’re heart-meltingly cute, which is. (Well, most of them are fast. One is still contentedly rounding the quarter pole after the other three racers are in the barn. This gives Mr. Johnson the opportunity to intone, “Sorry section three, I think your pig” – here it comes – “pulled a hamstring.”)

Shortly there’ll be a second race, with slightly more adolescent pigs, this time named after politicians. (Hello, “Nancy Piglosi.” Hi, “Donald Trumproast.”) It’s worth noting that some animal rights activists don’t like pig races, believing the animals are being exploited for human entertainment, but there’s certainly none of that sentiment in the stands today. In any case, the racers here aren’t the stars. The star, who now emerges from the trailer cradled against Mr. Johnson’s chest in a single giant hand, is little Swifty herself. Awwww.

But let’s leave Swifty for the moment; there’s a whole fair to see.

Back at the midway, among drifts of people surrounded by billboard-topped food stands pitching delicacies rarely seen in life, you’re struck both by the gloriously pre-pandemic feel of the experience and by the surprise of the event having been pulled together at all. When the pandemic shut down much of America in 2020, the organization behind San Diego’s fair lost a reported two-thirds of its employees. Then, to get the 2021 fair up and running, it had to reckon with its annual June opening – far earlier in the season than the other big fairs in places like Minnesota, Texas, Iowa, and Massachusetts, some of which run as late as October. The June date meant plans had to be made during the throes of COVID-19, long before it was possible to know what early summer might bring. The countless partners providing food, services, and entertainment had to be persuaded to make commitments amid the uncertainty. “They were just rolling the dice,” says one partner about the risks the fair’s planners took. “Bravo to them.”

It’s worked, mostly. Though the organizers are hesitant to be specific, several vendors estimate the 2021 fair to be only “a quarter its normal size.” Even late-season fairs like Minnesota’s have announced, “Recovery from the past year will take some time for many of our partners, so this year’s fair may look a little different from what we’re used to. I guarantee, though,” stated general manager Jerry Hammer, “that we will do our very best to give you the full-on Minnesota State Fair experience.”

A lot of things this summer may not quite provide the “full-on” pre-pandemic experience – but that won’t keep them from feeling pretty sweet. Or salty, as tastes could lean here on the San Diego midway. We’re headed for the “Extreme Dogs” performance (showtime 2 p.m.), but are having a hard time getting past the snack stands. You know what I’m talking about. I’m talking about giant grilled sausages, charbroiled corn, Texas funnel cakes, smoked barbecue sandwiches, cheese bread, kettle corn, “award-winning giant turkey legs,” “battered” potatoes, ice cream, lemonade, pizza covered in fruit, and bacon-wrapped hot dogs. We won’t even mention the fried dough, fried artichokes, fried avocados, and fried bananas. (“If you can eat it, we can fry it,” one server tells me.)

The bleachers for the “Extreme Dogs” event are packed. I squeeze in next to Rob Suarez, a house inspector from nearby Escondido, who has a multigeneration gang of family in tow. “Been looking forward to this,” he tells me while we wait, peering up at the Ferris wheel in the distance and the giant slide that rises to the south. “We come every year. I mean, except last year.” I ask him if he’s comfortable amid the jammed-in crowd after what we’ve all gone through. He looks at me slightly askance. “Sure. I mean, I worked straight through. Lots of people did. All these stories about people ‘uncomfortable’ coming back out of hiding?”

It makes him mad, he says. “It’s like reporters don’t realize that most people didn’t get to hide.

“But hey, I missed this!” he says, meaning the whole carnival around us. “And these dogs? They’re crazy.”

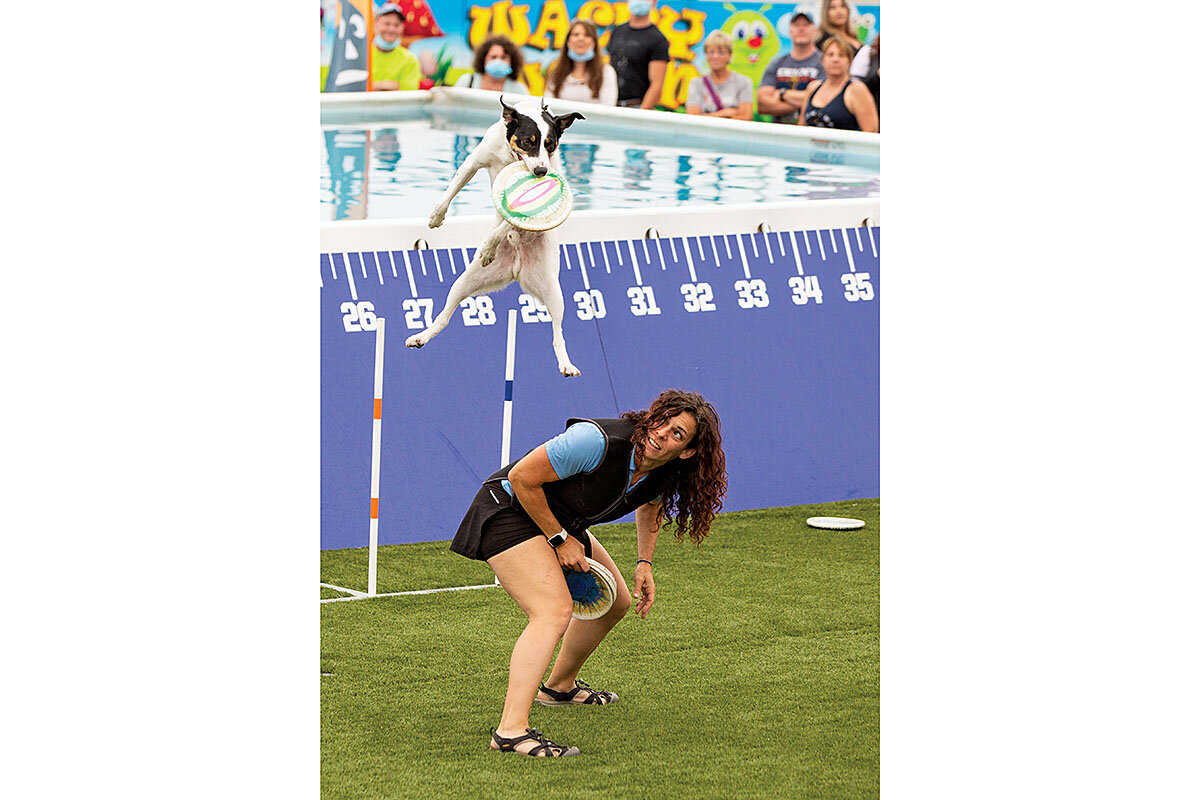

The dogs, when they perform, are crazy. They catch any flying disc launched, all while spinning, flipping, springing over their handlers, or jumping 30 feet into a pool. The crowd loves them. “And they love the crowd!” handler Andrea Rigler says later. “They get hyped!”

Ms. Rigler seems pretty hyped herself, especially when performing with her rescue dog Leap, with whom she’s won the open freestyle disc world championship three times. It’s easy to see why.

Later we ask Ms. Rigler if the fair this year seems any different from all the fairs and exhibitions in pre-pandemic days. “Oh, yes,” she says. “People are less angry.” Less angry? “Nobody’s worried about anything,” she says. “At last. And that’s it, right? What we’ve wanted? Quit worrying. You can feel it in the crowd.”

After the dogs, we traverse the fairgrounds again. Musicians are playing, corn is being piled on grills, people are hawking flags. In the multiacre shopping arcade people are plugging bamboo pillows, products by Lakeside Scissor Sales, and a machine promising “total body vibration, sitting or standing.” (It’s next to the House of Pistachios.)

Not far away, a man is milking a cow. Her name is Alena, she weighs 1,500 pounds, and every day she gives 14 gallons of milk. Also, like all cows, she can smell things 6 miles away. The things you learn.

Eventually, we’re at Swifty Swine again. We catch Mr. Johnson and ask how he got into this ... profession. He says, “Twenty-three years ago in Texas I saw these guys” – he means a nascent version of the current show – “and thought it was so cool. Talked to the owner and it turned out he was ready to sell. So I asked my wife, Shannon, who was in corporate marketing at the time, ‘Hey, you wanna race pigs?’”

“‘Sure,’ she said.”

OK, then.

Now it’s showtime again. The pigs race. (This time it’s Kardashing-ham, by a snout.) And then out comes Swifty, ready to fly into her stainless steel water trough. In truth, Swifty is more of a swimmer than a flyer. Still, there’s a moment – your heart jumps at it – when she leaps from her platform and has nothing below her but sky. Then she splashes into the trough and paddles across it at speed.

Watching beside me, Woz Jackson carries his daughter Kamelia on his shoulders. She claps, points, shrieks, and sighs the whole show – and says as soon as it’s over, “Daddy, can we get a pig?” Mr. Jackson just looks at me, laughs, and says to his daughter those words that every parent has wielded in crisis, “We’ll see, honey. We’ll see.”

I tell him I’m surprised kids still go for such analog events as this. Does he have any guesses why high-tech entertainment hasn’t rendered this sort of thing passé?

He shrugs. “Don’t know. All I know is my kids would kill me if we missed the fair.

“It’s a tradition,” he says.

Then he adds, shaking his head, “But how am I gonna not get a pig?”

A tradition, fairs definitely are – though that tradition has proved remarkably plastic, morphing over the centuries as fast as civilization and technology forced it to. The Romans held fairs. Medieval villages staged fairs so that potential customers would be present when merchants congregated. Renaissance fairs (“faires”?) were apparently so much fun that today a whole industry exists to reenact them. The very first modern state or county fair was held in 1841 in Syracuse, New York. (Among its attractions: a plowing contest. Who needs TikTok?) From it grew the tradition of the community agricultural fair, often timed to celebrate the harvest and provide those working the fields some respite and social pleasure. Agricultural fairs were a tacit recognition of communal interdependence. And a chance to boast. “Nice 800-pound squash you’ve got there, Eldrick. How do you like my 1,000-pounder?” In time, the “ag” element shrank, the pleasure element grew. With electricity came nighttime entertainment. With engines came rides. With amplification came noise.

Fairs turned into showbiz, literally. The movie “State Fair” appeared in 1933, was nominated for best picture, and sparked two remakes (1945, 1962) as well as – 63 years later – a Broadway musical. Its plot chronicles the Frake family’s annual sojourn from small farm to the biggest event imaginable: the Iowa State Fair. The elder Frakes have competition in mind (pigs, pies); the younger Frakes, romance. They all find what they came for – though exactly in what fashion they find it, I won’t spoil.

Is it a surprise that the movies aren’t bad? Maybe it shouldn’t be, because for all the recipe-contest high jinks and love-match folderol, what the movies do best is bring to life what makes us love fairs in the first place. Their size, their sound, the exotica of their games, shows, rides, and exhibits. Their version of the world. I first saw “State Fair” as a kid, and I couldn’t think anything but ... I want to go.

I certainly understood why the Frakes wanted to go. But only later did I realize that their journey from innocence to experience was one of those archetypal narratives that we intuitively crave, the tale of leaving town and encountering “the other.” It’s the story of the hero’s metamorphosis. For the Frakes, the Iowa State Fair offered at a minimum an escape from their mundane routine. At the maximum it held the possibility of slipping out of one’s skin and stumbling into an adventure. Where might it lead?

This year, of all years, we might wonder. Last summer there were no fairs, no amusement parks, no parades to speak of, no music festivals thronged with crowds. Leave town? Many of us haven’t left our houses. And if we’ve encountered “the other,” it’s been via Zoom.

“A city needs its dreams,” wrote the great design anthropologist Christopher Alexander in “A Pattern Language,” his team’s seminal handbook on how to construct towns and houses based on centuries of human experience. One prescription for how to conjure those dreams? “Set aside some part of the town as a carnival – mad sideshows, tournaments, acts, competitions, dancing, music, street theater, clowns ... which allow people to reveal their madness; weave a wide pedestrian street through this area; run booths along the [alleys].” So it is at the fair. So it was in San Diego on the midway – people finally free to reveal their madness, however civilized. Wander the “wide pedestrian street” here and you might see anything. You might see a man on a 7-foot unicycle juggling machetes. You might see a rescue dog become a superhero.

You might see a flying pig.

So, wanna meet Swifty? Of course you do. Just like the 43 people who are lined up right now, only minutes after the 4:30 show. For $10, Mr. Johnson has promised, you can hold Swifty and get a picture to commemorate the moment (he calls it a “pig-ture”). Full color, 5-by-7, yours in 30 seconds, thank you.

To judge by who’s lined up, Swifty appeals to all ages. “You can play on your phone all day,” Mr. Johnson observes, “but how often can you hold a pig?” Swifty by now has been toweled off and swaddled, and appears to accept her devotees with affectionate grace.

“She’s not bristly!” says Delaynee Martinez, age 11, after holding Swifty for a photo alongside her cousins.

The line grows longer.

We head back across the park to find the charismatic Ms. Rigler on break before the last “Extreme Dogs” performance of the day. This is her first event since the pandemic’s onset in March 2020, and she tells us about her year of “getting by” – doing online dog training and driving rescue dogs from one part of America to another. Now, “I’m just happy to be back out. It’s a breath of relief.” Things are normalizing; her performance and competition schedule is filling up. She glances toward the parking lot a hundred yards away, where a smorgasbord of RVs are wedged cheek by jowl. One of them is hers, and inside are her 10 dogs. Ten? “They’re our pets, too,” she says.

As we part with her, the sky has begun shading toward evening. Streaks of lilac in cornflower blue.

We aim for the exit, but the river of people has other ideas. Somehow we’re sweeping again toward the pigs. The 8 p.m. show is about to begin, and even from far away you can see the grandstands are now overflowing. There are baby strollers, wheelchairs, children on their parents’ shoulders. As we walk, we’re passed by a little girl tugging her mother in the direction of the tiny arena. “Mommy, are they going to race? Is that where they’re going to race?”

Oh, they’re going to race, all right. By the time we’re nearby, they are racing. And we don’t intend to watch them again. Really, we don’t.

Except that this time the buzz is even louder than before, the gravity of its energy pulling people from the sideshows, the arcade, the picnic tables. Around us the lamps are coming on, the carnival air is electric, and we’re all together, at last, all finding the groove of those timeless summer rhythms. And then from inside I start to hear it: “Go Swifty, go!” Louder now, feeding on itself. “Go Swifty, go! Go Swifty, go!” And I’m thinking, What will it be like this time? How astonishing? How preposterous?

So forgive me, but I have to leave you now, because Swifty’s about to fly again.

And, sure, you can blame it on my too-long-cooped-up heart, but I need to see how far.