Creativity: Artists find it both abundant and scarce during crisis

Loading...

| Fall River, Mass.

The month of April was supposed to be full of travel and public events for artist Brian Fox, whose realistic depictions of pro athletes and rock stars make him a sought-after talent. But when everything was canceled due to the COVID-19 crisis, he suddenly found 50 to 60 hours a week to devote to projects that have deep meaning for him personally.

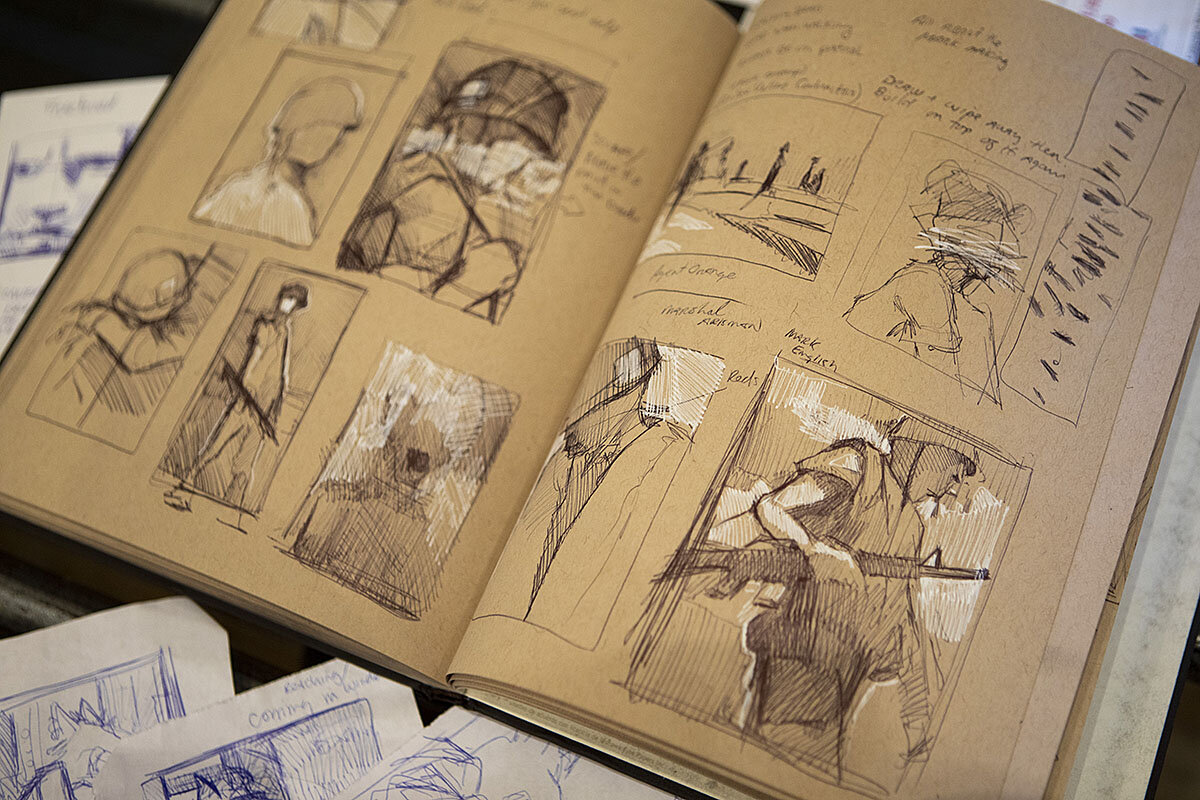

“I’ve got books full of ideas, but I’ve never had the time to take some of the best ones and ... really develop them,” Mr. Fox says at his riverside studio, where paintings of Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler now share space with a life-size Vietnam War scene. A pile of sketchbooks, filled up since the pandemic began, reveals what Vietnam veterans have been telling him lately.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Why We Wrote This

Can creativity actually increase during a lockdown? Artists are finding ways to invigorate their work by branching out and adapting to changed circumstances.

“I want to tell their story,” Mr. Fox says. “I asked the veterans, What do you want people to never forget? They said, ‘Never forget the ones who never came home.’ It’s all about that.”

From Mr. Fox’s studio in a converted textile mill in Fall River, Massachusetts, to dining rooms turned workshops during quarantine, creative people are seizing a moment oddly marked by both abundance and scarcity. With orders to stay home, they’re reveling in unexpected hours to finally finish, or at least advance, projects they’ve been keeping on the back burner. On a practical level, they’re also adapting to constraints, such as the need to make do with materials already at hand and to produce work that can be sold at lower price points.

“People are just going from one medium to another, doing whatever they have to do to survive,” says Gail Karr, chairwoman of the Northern New Mexico Fine Arts & Crafts Guild. “I don’t think anybody is expecting big bucks right away because nobody’s got them to spend” on artwork.

Artists are also pioneering works they hope will be valued by an anxious world – and will soothe their own souls in the process. Finding that sweet spot involves branching out beyond familiar creative processes.

“There is good study and good conversation that says, out of lament, out of crisis, out of grief – creativity flourishes,” says John Pfautz, who convenes the Center for Creativity committee at Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois, and is co-chairman of the music department. “Creativity finds a foothold in times like these.”

That’s because artists embrace new perspectives, Professor Pfautz says, and they are currently investigating what the pandemic has upended. They’re also communicating losses that can’t easily be put into words, such as the regret felt by one tapestry-maker who can’t travel to see her grandchildren in Israel.

“Art speaks where casual conversation or typical letter writing doesn’t,” Professor Pfautz says. “The violin player who can’t perform. ... The tapestry-maker who can’t see her family. ... They all have a way of articulating that lament in a way that we can connect with.”

Embracing a pandemic rhythm in Santa Fe

Springtime normally means lots of packing, driving, and unpacking for Maria and Miro Kenarov, a married pair of Bulgarian-born artists who sell at regional art festivals from Houston, Texas, to Palm Springs, California. But when eight upcoming shows were canceled this year, they hunkered down in ways that are already shaping the arcs of their careers.

Ms. Kenarova, a ceramicist, has started working with a long-accumulated store of beads and stones to make necklaces. Another new collection combines clay, fused glass, and photos in mixed-media pieces for wall display. Constraint “is something that provokes my creativity: What can I add here to make it more interesting, or what can I experiment with?” she says.

Mr. Kenarov, a painter known for his desert scenes, sees a modified business model emerging around a greater online presence. For the first time, he’s begun selling his work at virtual art shows and exploring partnerships with online galleries. If he can replace some of his art-show income with online sales, he says, the couple won’t need to travel as much – and can spend more time in Santa Fe, New Mexico, actually making art. “We’ve been here 28 years, and I’ve never before had two months in the studio,” he says.

Dedication to routine, such as the Kenarovs’ 8 to 10 hours a day in the studio, enables creativity to flourish even in unnerving times, according to Jonathan Feinstein, a professor who teaches creativity and innovation at the Yale School of Management. He noticed in his course this spring that students who structured their days and maintained a discipline, such as practicing a musical instrument, were more relaxed and prolific. Others needed to establish habits to keep anxiety from interfering.

“With this pandemic, yes, we have more time, but how do we use the time?” Professor Feinstein asks. “Creativity does best when people have habits and routines.”

Goodbye melting glass, hello tiny beads

Janet Hayes of Oakland, California, has had to reinvent herself because what she did up until March – glass flameworking – isn’t available to her anymore. She teaches at The Crucible, a nonprofit industrial arts school in Oakland. In a studio there, she uses a torch to melt glass to become sculptures such as paperweights or animal figures – or at least she did. Gone, at least for now, is her access to various types of glass-working equipment, including a kiln where she’d make glass platters, bowls, and trays. Also gone is the sense of excitement and danger associated with molten glass.

“Once you melt the glass, you have to pretty much go with it,” Ms. Hayes says. “You have to allow it to flow the way it’s going to flow. The more complicated the pieces are ... the more opportunity for variations and chance to take over.”

Her impromptu replacement art form couldn’t be more different. She’s now making beaded necklaces and bracelets in the two-bedroom apartment where she lives with her husband and 10-year-old son.

Jewelry-making at a dining room table is just right for this moment, she says, because it meets the pandemic-season needs of her family. It allows her to stop and restart a project many times a day, which means she can manage at-home interruptions and tend to her son while he can’t go to school.

She’s confident students could learn how to make jewelry via videoconference, and hopes to offer online classes this summer if The Crucible remains closed.

And unlike hot glass, the materials are controllable – a good fit for disorienting times when almost everything else feels unpredictable. “It’s precise,” Ms. Hayes says. “It’s easy to control. And you can get incredibly detailed with it. It’s a very domestic art; it’s not a studio art. And we’re all kind of living these domestic lives now, where we’re cooking, organizing, writing, mending clothes – so it fits well with all of that.”

“Out of the man caves”

Even the most in-demand artists are balancing what’s fulfilling with what can pay the bills. Consider Mr. Fox, the Fall River painter whose commissioned work hangs in homes of clients like NFL star Tom Brady. His originals sell for $3,500 to $50,000, he says. But lately he’s been adding to a noncommissioned series of playful werewolf images that help broaden his appeal beyond his largely male clientele.

“That’s man cave material,” he says, pointing to his football paintings. “One guy who buys all this sports stuff bought four or five original werewolf paintings, big ones for $15,000 or $20,000 apiece, and he put them in his living room” where his wife and houseguests will see them.

“The werewolf broadens my commercial value because I’m now out of the man caves,” Mr. Fox says.

Yet even as they exploit new opportunities, artists say something bigger is also afoot. The pandemic has served up time to release a bit of what’s been waiting inside to come out. Now they’re glimpsing what they’re capable of creating – if only they had the time.

“We all have abilities, and we are not given those by mistake,” Mr. Fox says. “The original ideas I have, need to be explored. Otherwise I’d be wasting a God-given gift.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.