Facebook's Rooms app experiments with pseudonymity, unsearchability

Loading...

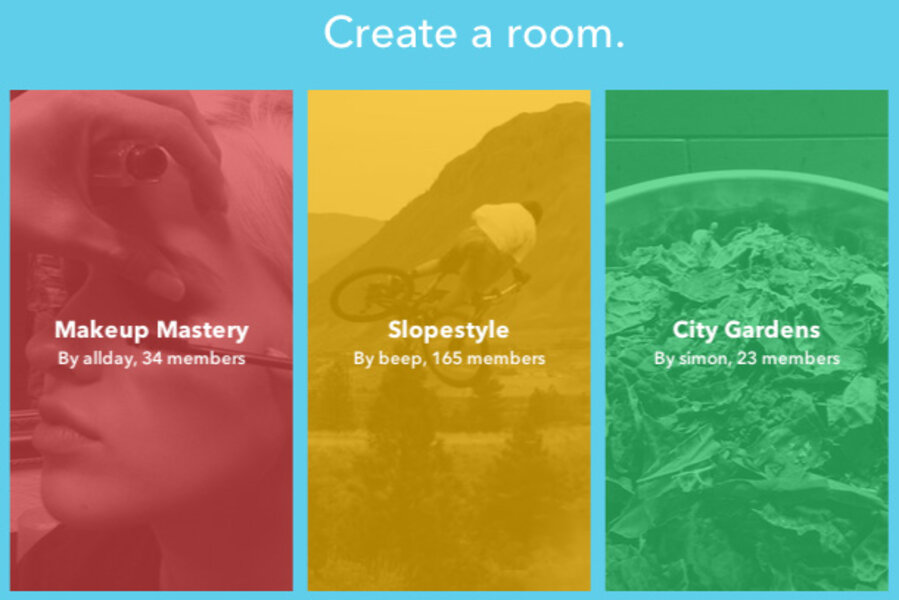

On Oct. 26, Facebook released Rooms, an iOS app that allows users to create and join anonymous chatrooms that revolve around common interests.

The chatrooms are public but not searchable, and invitations to them are facilitated through generated QR codes. All rooms are self-moderated and, if need be, users can report offending rooms to Facebook. Inside these rooms, users can post photos, text, or videos in a group stream. Users can choose whether or not to make themselves identifiable with a pseudonym.

"In the extent that the Internet has allowed for more anonymity, I think it’s had a more negative effect on society," says Leonard Shedletsky, a professor of communication at the University of Southern Maine. Mr. Shedletsky believes that though users of Rooms can find themselves using the app productively to discuss shared interests, the anonymity factor is still concerning.

"I’m sure it has moments where it serves a purpose, when you want to free people from what they want to say. But there are many times when anonymity is potentially destructive," he says.

A distinction in the app is its lack of a directory of rooms, a limit which Facebook’s product manager, Josh Miller, says is a feature that hearkens back to days when search engines didn’t dominate browsing and when users simply had to know where their haunt was on the Web.

“Though counterintuitive, our logic was that retro web browsers didn’t offer 'discovery' for early internet communities – you had to tell Netscape exactly where you wanted to go – so why should we?” Mr. Miller said in a launch post on Medium.

Without a working directory of rooms, users started sending room invites through social media websites with the hashtag #roomsapp to discover new rooms to join. It's a network that practically asks its users to leave Rooms and look elsewhere to engage.

But what does Facebook have to gain from releasing a product that’s by and large segregated from the rest of its suite of services?

“They’re confident they can generate enough cash,” says Brian Blau, an analyst at Gartner, a technology research company. “They really want to have diversity and in finding a wide variety of ways to get users to interact with their services. They’re gonna invest a lot into figuring out other markets.”

Mr. Blau says that Facebook is playing the long game, experimenting with services that may or may not flop, but in the end the successes will justify the flops.

“They said, ‘hey we have a really great opportunity to make revenues later, but now we need to have a lot of users.’ After they get that, then they can slowly start to monetize them,” Blau says.

Blau says that Facebook spends very little money for what it could potentially gain from experimenting with Rooms. After all, it wasn’t built from scratch.

Miller was hired from Branch, a service that Facebook acquired in January, to join Facebook’s Conversations group “with the goal of helping people connect with others around their interests.”

While Rooms itself is novel, it borrows elements from Branch, which was similarly focused on threading conversations around a common subject or interest.

While the service looks back to days when Internet users had to connect directly to bulletin board systems to send messages and files, it distances itself by fostering a sort of community inside and outside of its boundaries. And if usage and discussion on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook have brought more users into Facebook’s ecosystem, then it’s succeeded in its mission.

[Editor's note: The original version of this article misstated the name of the university at which Leonard Shedletsky teaches. It is the University of Southern Maine.]