Raspberry Pi: Rise of the $25 computer

Loading...

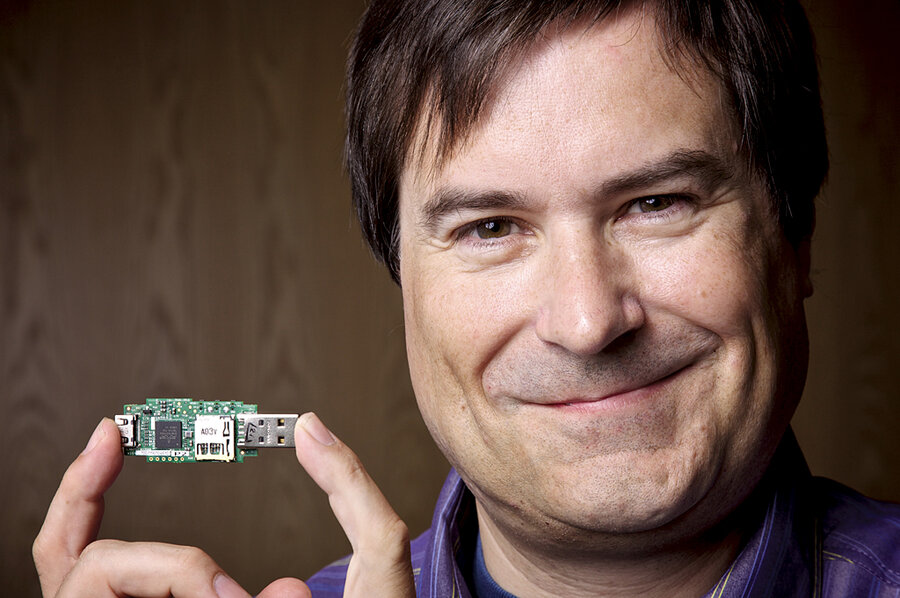

David Braben has a big idea crammed into a tiny frame. He and fellow members of the British nonprofit Raspberry Pi have designed a rugged computer powerful enough to perhaps inspire a generation of future programmers, yet cheap enough that schools can hand them out free of charge.

The machine isn't much to look at. It's little more than chips on a stick. But Mr. Braben says that by next year, this ugly duckling of a prototype could grow into $25 computers tailored to students across Britain.

"Raspberry Pi came from a seemingly unrelated problem," says Braben, who's also chairman of Frontier Developments, a video-game company in Britain. He felt that the number of qualified computer science graduates had declined over the years. Curious, he consulted teachers and grew concerned about what he found.

Since the 1990s, he says, school computers have been little more than office tools. Students learn to write letters, produce spreadsheets, and generally operate Windows software.

"It's a useful skill for almost everybody, but the problem is that that can backfire," he says. "A lot of kids are already quite computer literate and [such lessons] come over as being very dull. Meanwhile, teaching computer science in schools – I mean programming and using the computer creatively – has all but gone away."

The creative spirit is there, he says. Just look at pop culture. Video games such as the blockbuster Halo: Reach, fan favorite Little Big Planet, and The Sims series have made millions by letting players design and craft their own worlds. Yet this is low-level programming. There's a gulf between the accessible but limited tools offered by popular games and the complex but expensive software used by the professionals who programmed them.

There was once a middle ground, remembers Braben. The Apple II, Acorn Electron, and BBC Micro from the early 1980s required a little programming to make the most of them. If that peek behind the curtain interested kids, they were free to explore everything else the computers could do. Raspberry Pi hopes its machine can fill this role and renew interest in creative programming, especially among low-income families that couldn't afford a computer otherwise.

The prototype distills hardware into the essentials. It has a powerful processor similar to those in high-end smart phones, a memory card reader for 32 gigabytes of storage, a screen connector ready for HD graphics, and up to three USB ports for a keyboard and other accessories.

Raspberry Pi's open-source software can handle everything that kids now come to expect – Web browser, e-mail, Facebook access – while providing tools to program and share their own creations. If a student deletes essential files by mistake or creates inappropriate material, a simple command will wipe the drive and return the machine to its original state (a trick common among the early computers that Raspberry Pi is emulating).

The device also has glaring omissions. There's no screen, because nearly every living room in Britain already has one – the TV. Televisions also supply the power, so no battery is needed. Keyboards can be bought cheaply in bulk or borrowed from another machine, keeping costs low.

"We said, 'Let's get rid of the fragile, expensive bits,' " says Braben, the de facto spokesman for Raspberry Pi. The other members of the group work on the project while keeping their day jobs in the computer industry and academia.

According to Raspberry Pi's calculations, the group could hand out one of these PCs to every child in Britain in a particular grade for $24 million. They hope to partner with a corporation or nonprofit to fund the manufacturing, keeping the computers completely free of charge for students. That partner would also get the first crack at naming the machine.

Within a few years, Braben says, every child could own one of these com-puters from age 11 until graduating high school.

If the program takes off, Braben says he'd like to take Raspberry Pi overseas, much like the One Laptop Per Child project. The international nonprofit has faced harsh realities in its first six years, but also enjoyed many quiet victories, says OLPC chairman Rodrigo Arboleda Halaby. Its "$100 laptop" still costs around $200, and the group's vision of operating off donations alone never came true.

Yet OLPC has sold more than 2 million low-cost laptops, primarily to developing countries. In fact, since 2009, all 395,000 students entering first through sixth grade in Uruguay have an OLPC computer. The program will soon extend into high schools as well. While the group waits for official studies into how its computers have changed classrooms, Mr. Arboleda says he's delighted to see kids blossom into skilled programmers.

"Debugging a program is the most perfect way of learning," he says. "We have already 12-year-old children in Uruguay that are proficient programmers. You cannot imagine the stuff we are beginning to see in these young kids."