China asserts itself in GPS turf war

Loading...

| Beijing

At the European Union’s embassy in Beijing, a recently built extension bears the name “Galileo.” It celebrates one of Europe’s most high-profile and symbolic partnerships with China, but it might soon have to be rechristened.

China’s membership of “Galileo,” the European-led version of America’s Global Positioning System (GPS), has soured to the point where the two sides are locked in a dispute over radio frequencies, as China races ahead with its own network of satellites.

Cooperation has turned to confrontation.

Without an agreement, China would be able to frustrate European military forces’ efforts to deny a future enemy crucial satnav capability. Some expert observers suggest that may even be Beijing’s goal.

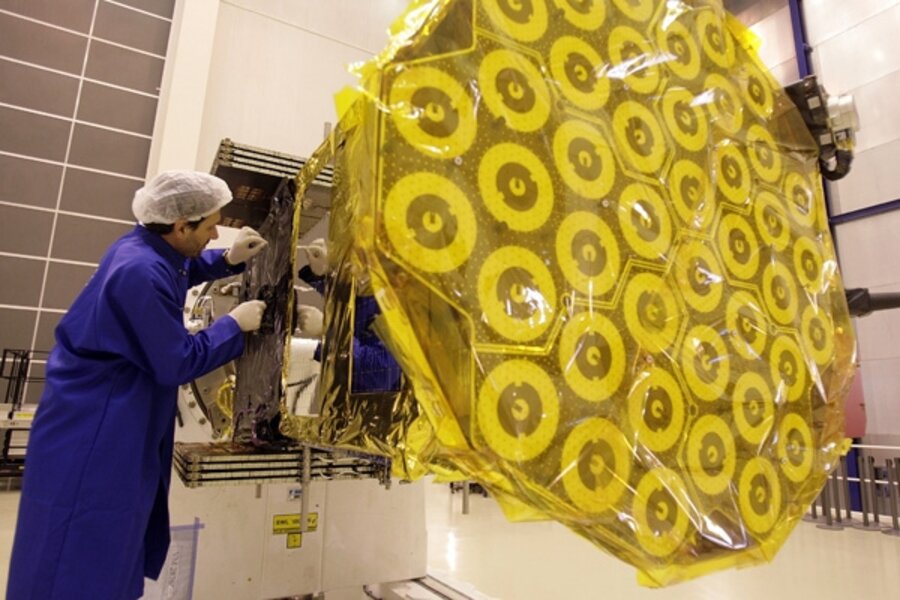

As the EU prepares to sign contracts this year with satellite builders and China plans the June launch of the first satellite in its own “Compass 2” constellation, “both are at stages of program development that make this an urgent question,” says Glenn Gibbons, editor of “Inside GNSS” magazine.

GPS, Galileo, and Compass, along with the Russian “Glonass,” are building the satellite infrastructure for an increasingly important technology used for purposes ranging from nuclear missile guidance, through mapping, to steering a mobile-phone user to the nearest Starbucks.

Their designers are publicly committed to making these systems inter-operable, and their signals part of the global commons. If China and Europe resolve their spat, “they should be synergistic,” says Mr. Gibbons. “Together they could create a more robust and reliable system of signals.”

From cooperation to competition

More than a decade ago the EU, unhappy with its dependence on the US-owned and controlled GPS, set out to build its own system and invited other countries to join.

When China signed up in 2003 it was a major coup for then-French President Jacques Chirac’s vision of a “multipolar” world in which US influence would be diluted. Later, however, the Europeans got cold feet, denying Beijing a seat on the Supervisory Authority, which owns and oversees Galileo, for security reasons.

“The Chinese felt insulted and disrespected,” says Taylor Dinerman, a US space expert. China’s treatment at Europe’s hands “really moved the Chinese schedule ahead” in the construction of Beijing’s own system, adds Eric Hagt, a space analyst at the World Security Institute, a Washington-based think tank.

“We felt that we were not treated equally,” explains Shen Dingli, a national security expert at Fudan University in Shanghai. “In fact, China has no big need to join Galileo and Europe forced China to understand this.

“As a major power,” he adds, “China needs to assure its national economic and security independence. These will in turn assure its political independence.”

China: Securing a strategic space

That thinking echoes Europe’s own reasons for building Galileo. The problem for Europe is that China has chosen for Compass the same signal frequency as Galileo will use for its encrypted, security-oriented Public Regulated Service (PRS).

There is no law against that, so long as the Compass signals do not interfere with Galileo’s. But in the event of a conflict, it means that European forces could not jam Compass’s publicly available signal – which an enemy could use – without jamming its own secure signal.

“The question arises whether this is payback for being booted out of Galileo,” suggests Mr. Hagt.

European Commission spokesman Fabio Pirotta says that Brussels is “hopeful to be able to reach some form of solution to the issue” since “without technical agreements ... there is a risk of interference that would make signals of both systems unusable for the users.”

After two recent rounds of negotiation, however, China still has not responded to engineering suggestions the EU has made to solve the problem. There are signs it will go ahead with its program regardless.

“We hope to get agreement [with Galileo] before we launch” the first Compass 2 satellite scheduled for June, “but we cannot wait to do the validation and development of the system,” Jing Guifei told an international satnav summit in Munich earlier this month, according to a participant.

“To make China move [to a new frequency] the Europeans have to offer good enough compensation,” argues Professor Shen. “If that frequency has unique military advantages, we are not going to trade. Otherwise, it is up to the Europeans to think what they shall do.”

US, Europe also tussled over turf

In a similar dispute a few years ago, when Washington felt that Galileo’s proposed signal frequency was too close to its own GPS frequency, Europe was persuaded to find a new spot on the spectrum by offers of US technological help with Galileo. It is unclear whether Europe might make a similar offer to Beijing, or whether Beijing would accept it.

The dispute illustrates the difficulty of building a seamless, interoperable network of global navigational satellite systems (GNSS) that would reinforce each others’ accuracy and reliability.

“There are a lot of reasons to make these systems noncompetitive and nonconfrontational,” says Gibbons. “Everyone would benefit from building the market by increasing the number of places where GNSS navigation and timing can be used reliably.”

Unfortunately, he adds, “although all four talk about interoperability, they are separate, independent critical strategic systems operated by countries that do not always have the same strategic interests.”