Colleges wean off fossil fuels

Loading...

| Middlebury, Vt.

With the sun shining on a rare, warm winter day, Thomas Corbin stands in a snow-covered field of willow shrubs. The stalks, some more than 10 feet high, jab like slender fingers into the blue sky.

If all goes well, in two years, a modified corn harvester will chop through these fast-growing shrubs. The crop will then be hauled a mile or so to feed the new biomass gasification plant at Middlebury College, where Mr. Corbin is assistant treasurer. The college hopes that the willow will provide 12,000 tons of fuel each year, about half of the fuel the facility is expected to burn.

The Middlebury plant, which opened earlier this year, provides both heat and electricity to the campus. It runs on wood chips that come from within a 75-mile radius of this campus of 2,400 students in northwestern Vermont. The plant, which cost about $12 million to build, will replace about half of the 2 million gallons of heating oil the school burns annually and reduce carbon emissions by an estimated 12,500 metric tons per year.

More and more, colleges and universities are not only teaching about environmental issues, they’re “walking the walk” by changing they way they operate. In December 2006, 12 college and university presidents joined together to form the American College and University Presidents’ Climate Commitment. They pledged to set target dates for becoming carbon neutral – reducing the carbon emissions from their heating, cooling, electrical, and transportation needs as much as possible and then buying carbon offsets to complete the task. A little more than two years later, 614 colleges and universities in all 50 states have made the commitment. They represent about one-third of the student body at colleges and universities in the United States.

Interest on college campuses in taking steps to slow climate change have “exploded,” says Anthony Cortese, president of Second Nature, a Boston-based nonprofit group that works with colleges on environmental and sustainability issues.

“It’s exponential growth. It’s terrific.”

Middlebury is hardly alone among colleges in trying to wean itself off fossil fuels:

•In Bar Harbor, Maine, the College of the Atlantic recently fired up a wood-pellet boiler that generates heat for three student residences and the campus center, about one-fifth of the campus. The pellets are made of sawdust from a lumber mill in northern Maine. The college, which has signed the presidents’ commitment, has pledged to rely solely on energy from renewable sources by 2015.

•At the University of Minnesota, Morris, a new biomass gasification facility is being tested that will use corn stover and other local agricultural waste to replace as much as 80 percent of the campus’s heating and cooling needs now generated by fossil fuels, mainly natural gas.

“We can find enough biomass within 20 miles to easily supply our needs,” says Joel Tallaksen, the biomass project coordinator at Minnesota-Morris. “In our area there’s just not enough wood” to burn wood chips or pellets, he says. But there is a plentiful supply of corn stalks, wheat straw, and soybean residue. The university will need about 4,000 to 5,000 acres of material per year, and the surrounding county has about 150,000 acres of corn crop alone, he says.

The Minnesota-Morris facility is completed but has yet to open, having encountered technical hurdles that the general contractor must first fix, Mr. Tallaksen says.

•The University of New Hampshire in Durham plans to provide 80 percent of its heating and electrical needs by buying and burning methane gas given off by a landfill a few miles away, making it the first university in the United States to be fueled primarily by landfill methane gas.

“There are some really outstanding examples everywhere” around the country, says Dr. Cortese of Second Nature.

At Middlebury, the wood-chip boiler represents a big step toward the school’s goal of becoming entirely carbon neutral by 2016. It reduces the school’s carbon footprint by about 40 percent, making it “a big, bright spot on the path to carbon neutrality,” says Jack Byrne, the campus director of sustainability integration.

Ahead lies “the next million gallons” question, he says: How to eliminate the rest of the fossil fuels still being burned each year for heating, cooking, and cooling. One option may be to replace the rest of the oil-fired boilers with wood-chip or other biomass boilers. The school will buy carbon offsets – which pay other organizations to reduce their carbon emissions to compensate for emissions – only as a last resort.

Middlebury’s wood chips currently cost about 40 percent less than the equivalent amount of heating oil. The expected break-even point for the cost of the plant is about 12 years, less than half its expected working life of 25 years. The payback could come even sooner if energy prices spike as they did last year, says Mike Moser, heating plant engineer at Middlebury College.

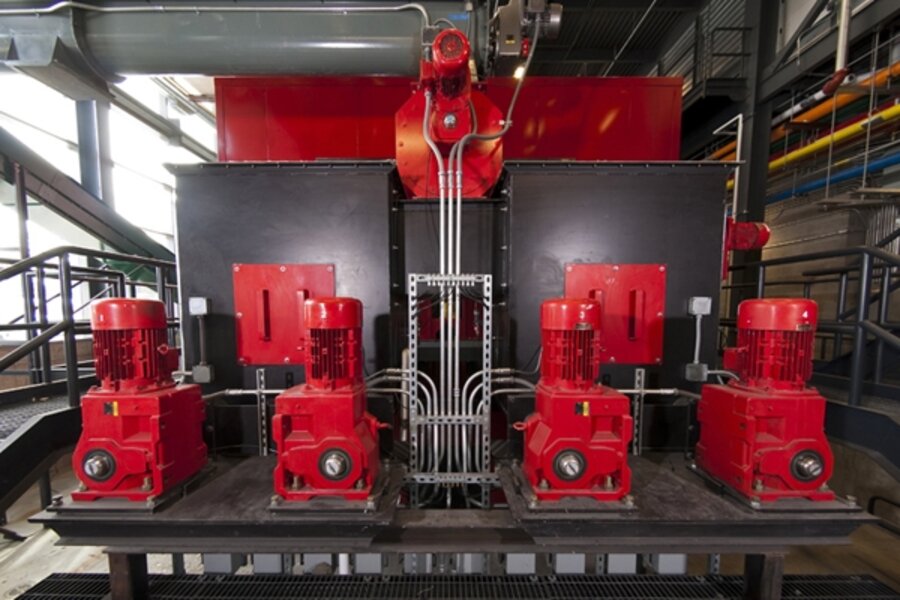

The wood-gasification process differs somewhat from the workings of a wood or wood-pellet stove. The chips are delivered by conveyor belt to a giant box, where they are “roasted,” driving off combustible gases. The gases are sent into another combustion chamber, where they are burned at temperatures up to 2,000 degrees F.

The college’s administration and governing board were very receptive to the idea of building a renewable-energy heating plant, says Tom McGinn, project manager at Middlebury, and liked the idea of cutting the need for imported oil. By using local wood, he says, you don’t end up with oil from Venezuela or the Middle East, but with fuel from some local “guy with a chain saw.”

“We’re supporting the local economy, and we’re definitely providing a financial benefit to the institution here,” Mr. McGinn says. “Where’s the downside?”

The college, which opened the first undergraduate environmental studies department in the country in 1965, is also experimenting with solar energy and has one wind turbine in operation. The college’s new environment center, opened last year, became the second academic structure in the nation to achieve LEED Platinum certification, the highest rating for a “green” building, and only the seventh LEED Platinum building in the US.

David Hales, president of the College of the Atlantic, argues that, as stock markets plummet, getting donors to sponsor campus environmental projects actually can be an easier sell. Projects that will pay back their cost in energy savings in two to seven years have great appeal, he says, when compared with donating stocks that may shrink in value.

“There are a lot of donors who say, ‘Oh, that makes a lot of sense. I can do that,’ ” he says. The projects act like “an endowment,” Dr. Hales says, that keeps growing in value through the years.