How to count the ‘invisibles’

Loading...

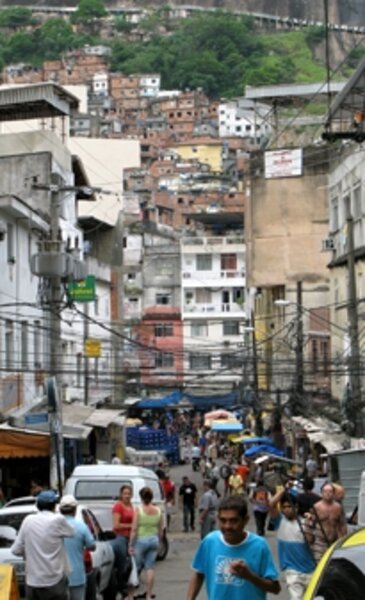

On a visit to a poor neighborhood, or favela, in Rio de Janeiro several years ago, Melanie Edwards asked how many people lived there. She heard estimates from 5,000 to 60,000. No one really knew.

They were “invisible,” just a small part of the 1 billion people around the world who are off the grid, lacking birth certificates, driver’s licenses, or voter registration cards. “They have nothing to show that they exist in the world,” Ms. Edwards says.

That information gap poses threats to both these people and everyone else. Without accurate data, governments and aid groups lack the ability to reach them effectively. At the same time, problems that might spread from these areas, such as epidemics, are likely to go undetected longer. Even businesses that would like to reach these people with helpful products and services are hampered by a dearth of knowledge about their specific needs.

Edwards, a former Peace Corps volunteer, has founded Mobile Metrix, a market research firm aimed at serving this “invisible” billion along with the rest of the 4 billion people – more than half of the world’s population – who subsist on less than $3,000 a year.

Mobile Metrix hires local youths to go into neighborhoods carrying PDAs, hand-held devices capable of storing and transmitting data as well as audio. Their work often paints a clearer picture of who lives there than government estimates or infrequent paper surveys that can be inaccurate or years out of date.

The PDAs allow information to be gathered more accurately and shared more quickly than with pencil and paper.

But the key Mobile Metrix innovation in early pilot programs in Brazil has been employing young people from the neighborhood, male and female, to conduct the surveys. These “mobile agents” must be recommended by a prominent community member, such as a church or nonprofit organization leader. They are trained in how to conduct a survey and how to use their PDA. A typical survey might ask 60 to 80 questions, such as “How many people live in the home?” and “What is their level of education?”

The mobile agents are 16 to 25 years old. “You see these youths transformed,” Edwards says. “That tends to be the age where they could be going into prostitution or the drug gangs, so we’re hoping this is an alternative to that. In several cases, we’ve had gang members come up and want to become involved.”

One applicant held up his hand during his job interview and showed that he’d lost two fingers, blown off by a hand grenade during a drug war. “He became one of our star mobile agents, and now he’s gotten into university, and he’s making three times the minimum wage in a high-tech job,” Edwards says.

Unlike in the United States, where people may sometimes be suspicious of visitors on their doorsteps, people in the favelas open up their homes to the mobile agents, often offering them food and drink, even “dressing up” for the interview, she says.

“I get a real sense that these are forgotten people,” Edwards says. “And this is their moment to have a voice.… They take it as an honor that someone wants to sit and talk with them.”

Edwards expects the clients of Mobile Metrix will be governments, aid organizations, and even corporations. It already has completed a survey on local knowledge in the favelas about Dengue fever, helping authorities determine the size of the problem and whether people know about preventative measures. It was backed by Johnson & Johnson, which also gave away free samples of its mosquito repellent. In a lot of cases “we found out that people didn’t even know what [mosquito] repellent was” or that such a product existed, she says.

Edwards, who also teaches a class on how to create a business with a goal of social good at Stanford University, notes that such surveys provide companies with valuable answers to questions such as “Is there a market there for us?” and “How do we reach these people?”

Mobile Metrix is one of many nonprofit and for-profit companies trying to use hand-held devices, especially cellphones, to reach remote areas and underserved people. Getting organizations like Mobile Metrix to use less expensive, ordinary cellphones instead of PDAs is one goal of DataDyne, a nonprofit company that is developing free, open-source software to collect data. The company’s EpiSurveyor program currently is being applied to study disease outbreaks and conditions at medical clinics but potentially could be used to gather any kind of information.

“As long as you have a data connection, you can use the service,” says cofounder Joel Selanikio, a one-time computer programmer who became a medical doctor and now uses both backgrounds in his work to bring medical services to developing countries.

Because EpiSurveyor is designed to be simple, anyone can download it and begin using it quickly, Dr. Selanikio says. The forms work on PDAs, but his ultimate goal is to “get this thing to run on any cellphone.”

Already, very simple surveys are possible on any phone using short text messages. Much more will be possible as more sophisticated phones become more common around the globe. When he visited Zambia recently, Selanikio noticed that a number of public health workers there already had Apple iPhones. “Every single public health officer in Africa is [already] walking around ... with a cellphone in their pocket,” he says. “Even more amazingly, they actually bought it themselves.”

Today a young public health official might be sent to a remote area and perhaps go years without any additional training. “Think what you could do if each of those people had an iPhone that you could send videos of [medical] lectures to,” he says.

Meanwhile, Edwards says Mobile Metrix would be eager to switch to a cellphone-based program when it’s available. Either way, technology is serving as a means to an end, which is getting the lives of the “invisible” noticed.

“It’s not just about counting lives,” she says, “but making those lives count.”