How ocean current could power half the homes in Florida

Loading...

Todd Janca spent a lot of time underwater as a kid. His father ran the Discovery Bay Marine Laboratory in Mona, Jamaica, and they would take the submarines deep into the ocean to do oceanographic research. While at those great depths, Mr. Janca remembers the submarine had to fight strong ocean currents.

“Along the way, it just dawned on me that no one is using all the energy that is down there,” he says. “You can collect the energy from [an ocean current] and you aren’t using anything up.”

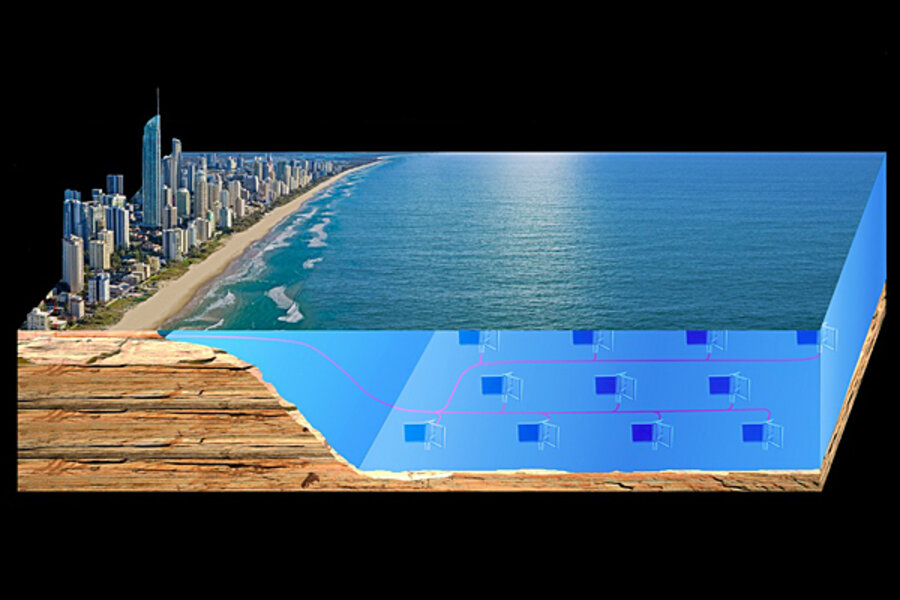

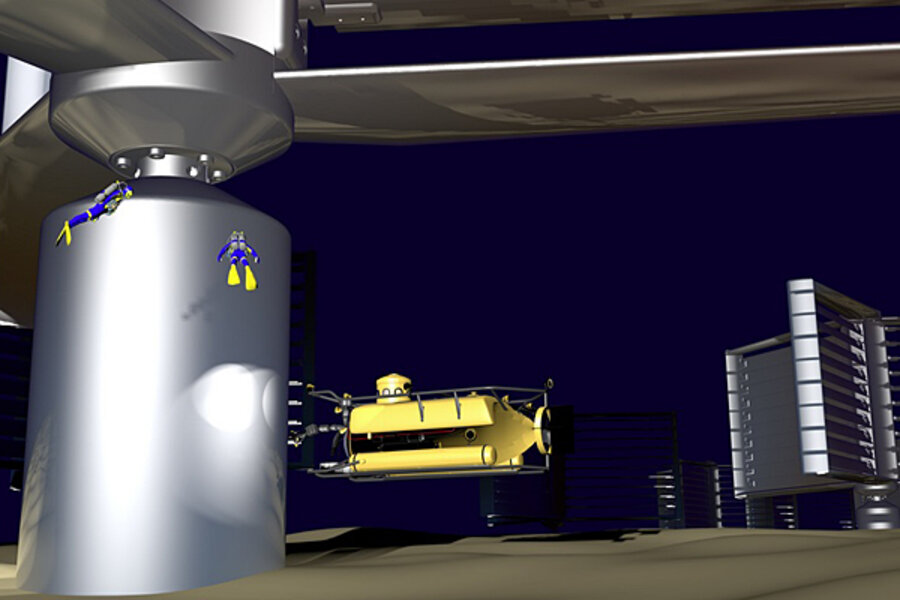

So this year, Janca started Crowd Energy, a company that is looking to build large underwater turbines to harness ocean currents. Crowd Energy, based in Zephyrhills, Fla., plans on making turbines with 100-foot-tall propellers located 300 feet below the ocean’s surface and miles from shore.

When people think about renewable energy, they often imagine solar panels and towering wind turbines. These sources of clean power are great for certain places, but shifting from fossil fuels to renewable energy will require tapping into many sources of power. The sun doesn’t shine at night, the wind doesn’t always blow, but deep ocean currents could provide continuous renewable power to coastal areas across the United States.

To make ocean current turbine farms a reality, Crowd Energy needs to test its design in the open water. So, Crowd Energy is trying to raise $1 million on Indiegogo to finish the research and to move the technology closer to commercial use.

“Crowd Energy’s technology has a huge amount of potential,” says Jon Wank, the chief operating officer of Solutions Project, a non-profit group, co-founded by actor Mark Ruffalo, to accelerate the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy. “They have to do some testing to see if the technology will scale. If it can, it will be a game changer.”

A study by the Georgia Institute of Technology into the energy production potential of ocean currents found that there are 5.1 gigawatts of untapped power off the coast of Florida alone. That’s equivalent to powering more than 3,800,000 homes for a year – more than half the households in the Sunshine State. The whole Gulf Stream could provide four times that amount of energy.

“With more than 50 percent of the population living within 50 miles of coastlines, there is vast potential to provide clean, renewable electricity to communities and cities across the United States using [marine technology],” the Department of Energy said in a statement to the Monitor.

The DOE has spent more than $100 million to research what’s known as marine hydrokinetic technologies, which includes energy from ocean currents, waves, and the tides. Wave energy uses the churning of the waves along the surface to spin a turbine. Several commercial wave farms are connected to the grid in Europe. Tidal energy is similar to ocean current energy but it harnesses power from the shift between low tide to high tide. Tidal technology has been tested in Maine and in Europe. Though these two forms of hydrokinetic energy are already being utilized, they are confined to the few places in the US with strong enough waves and large enough tidal range to produce a substantial amount of power.

The concept of ocean current energy has been around for almost a decade and has a lot of potential, but no design has ever been tested in the open water. If Crowd Energy raises enough money, the company will test its prototype at Florida Atlantic University, a leader in hydrokinetic research. The school’s Southeast National Marine Renewable Energy Center is working with a number of companies to begin testing ocean current turbine designs. The university has a tank to test the devices and is working on getting the country’s first open-water testing site off the coast of Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

“We have to get our device in the water and test some of the assumptions both we and the regulatory bodies made,” says Susan Skemp, director of the FAU research center.

One of the things that needs to be confirmed is that turbines won’t harm animal life. In addition to ensuring that no animals will be harmed by the physical turbine, Janca is trying to make the turbine as quiet as possible to minimize harmonics, which can affect animal life. Gabriel Alsenas, a program manager at FAU working with Crowd Energy, says the turbines move slowly enough that they won’t harm animals.

“The risk to animals is extremely low,” Mr. Alsenas says. “They would be able to interact with the turbines at their own leisure.”

The Monitor contacted a number of environmental advocacy groups, and none of them provided a statement for or against the technology.

Part of the challenge of making ocean current energy a viable renewable energy is finding a way to harness power from slower-moving currents around the rest of the country. The Gulf Stream’s current has an average speed of 4.4 miles per hour near Florida, but most of the currents around the country move at less than 1 mile per hour.

“If you’re going to put a propeller in a slow-moving current it won’t do anything, but our design is designed for slow-moving currents because it has a huge surface area,” Janca says. “The slower the water, the less energy you produce, but that doesn’t mean you can’t produce energy from slow moving water [with the right design].”

Crowd Energy has less than two weeks left on its Indiegogo campaign, and the company is struggling to raise money. In its current campaign, Crowd Energy has raised just $14,000. This isn’t the first time that the company has struggled to secure funding. Crowd Energy tried a Kickstarter campaign in June, spending $10,000 in marketing, but attracted around $30,000 in pledges. The company didn’t get a dime of that money because it failed to meet its $75,000 goal.

For now, Janca is funding the project from his own salary and says the money will keep the project going for the next few months. Crowd Energy will most likely do another fundraising campaign next year and is applying for government grants.

“Right now everyone we’ve shown the project to has been overwhelmingly positive. It’s just a matter of getting eyes on the project,” Janca says. “Every time we do a campaign, we get a lot more interest in what we are doing.”

While covering ocean current technology, one quickly learns there are a lot of questions that don’t have answers yet, but every person looking into the technology has faith. Lots of designs look promising. None are proven. But for states along the coast, ocean currents could be a viable source of renewable energy in the future.