Hacker: Airplane satellite communications are vulnerable

Loading...

| BOSTON

Cybersecurity researcher Ruben Santamarta says he has figured out how to hack the satellite communications equipment on passenger jets through their WiFi and inflight entertainment systems - a claim that, if confirmed, could prompt a review of aircraft security.

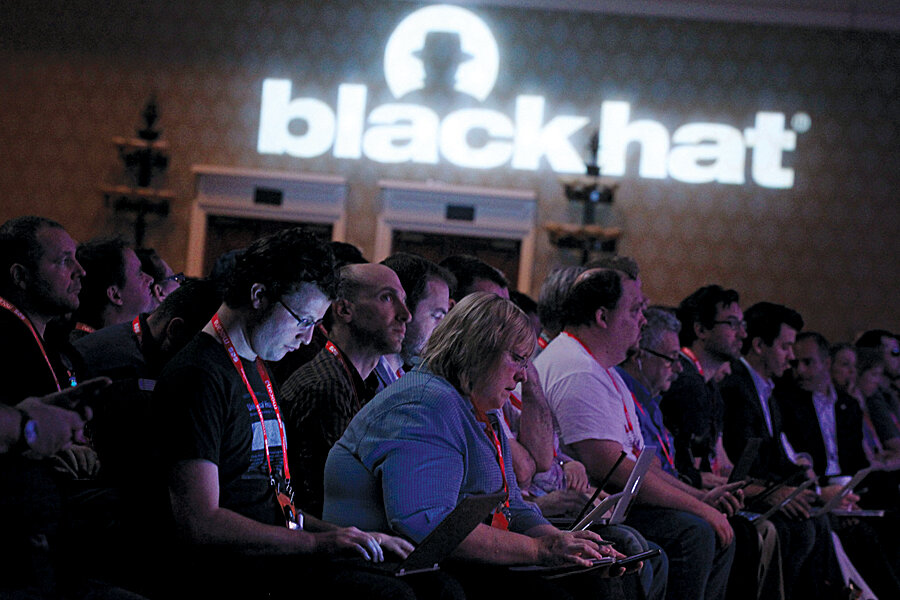

Santamarta, a consultant with cybersecurity firm IOActive, is scheduled to lay out the technical details of his research at this week's Black Hat hacking conference in Las Vegas, an annual convention where thousands of hackers and security experts meet to discuss emerging cyber threats and improve security measures.

His presentation on Thursday on vulnerabilities in satellite communications systems used in aerospace and other industries is expected to be one of the most widely watched at the conference.

"These devices are wide open. The goal of this talk is to help change that situation," Santamarta, 32, told Reuters.

The researcher said he discovered the vulnerabilities by "reverse engineering" - or decoding - highly specialized software known as firmware, used to operate communications equipment made by Cobham Plc, Harris Corp, EchoStar Corp's Hughes Network Systems, Iridium Communications Inc and Japan Radio Co Ltd.

In theory, a hacker could use a plane's onboard WiFi signal or inflight entertainment system to hack into its avionics equipment, potentially disrupting or modifying satellite communications, which could interfere with the aircraft's navigation and safety systems, Santamarta said.

He acknowledged that his hacks have only been tested in controlled environments, such as IOActive's Madrid laboratory, and they might be difficult to replicate in the real world. Santamarta said he decided to go public to encourage manufacturers to fix what he saw as risky security flaws.

Representatives for Cobham, Harris, Hughes and Iridium said they had reviewed Santamarta's research and confirmed some of his findings, but downplayed the risks.

For instance, Cobham, whose Aviation 700 aircraft satellite communications equipment was the focus of Santamarta's research, said it is not possible for hackers to use WiFi signals to interfere with critical systems that rely on satellite communications for navigation and safety. The hackers must have physical access to Cobham's equipment, according to Cobham spokesman Greg Caires.

"In the aviation and maritime markets we serve, there are strict requirements restricting such access to authorized personnel only," said Caires.

A Japan Radio Co spokesman declined to comment, saying information on such vulnerabilities was not public.

BUGGY 'FIRMWARE'

Black Hat, which was founded in 1997, has often been a venue for hackers to present breakthrough research. In 2009, Charlie Miller and Collin Mulliner demonstrated a method for attacking iPhones with malicious text messages, prompting Apple Inc to release a patch. In 2011, Jay Radcliffe demonstrated methods for attacking Medtronic Inc's insulin pumps, which helped prompt an industry review of security.

Santamarta published a 25-page research report in April that detailed what he said were multiple bugs in firmware used in satellite communications equipment made by Cobham, Harris, Hughes, Iridium and Japan Radio Co for a wide variety of industries, including aerospace, military, maritime transportation, energy and communications.

The report laid out scenarios by which hackers could launch attacks, though it did not provide the level of technical details that Santamarta said he will disclose at Black Hat.

Harris spokesman Jim Burke said the company had reviewed Santamarta's paper. "We concluded that the risk of compromise is very small," he said.

Iridium spokesman Diane Hockenberry said, "We have determined that the risk to Iridium subscribers is minimal, but we are taking precautionary measures to safeguard our users."

One vulnerability that Santamarta said he found in equipment from all five manufacturers was the use of "hardcoded" log-in credentials, which are designed to let service technicians access any piece of equipment with the same login and password.

The problem is that hackers can retrieve those passwords by hacking into the firmware, then use the credentials to access sensitive systems, Santamarta said.

Hughes spokeswoman Judy Blake said hardcoded credentials were "a necessary" feature for customer service. The worst hacker could do is to disable the communication link, she said.

Santamarta said he will respond to the comments from manufacturers during his presentation, then take questions during an open Q&A session after his talk.

Vincenzo Iozzo, a member of Black Hat's review board, said Santamarta's paper marked the first time a researcher had identified potentially devastating vulnerabilities in satellite communications equipment.

"I am not sure we can actually launch an attack from the passenger inflight entertainment system into the cockpit," he said. "The core point is the type of vulnerabilities he discovered are pretty scary just because they involve very basic security things that vendors should already be aware of."