Why Europe backpedals on biofuel targets

Loading...

| London

Europe is signaling a retreat from its bold commitment to biofuels as concern mounts that the plant-based alternative to gas and diesel, once heralded as a panacea for climate change, is contributing to spiraling global food prices.

Officially, the 27-nation European Union is sticking to a target that will require 10 percent of motor vehicle fuel to be derived from renewable sources by 2020, as part of overall efforts to reduce carbon emissions by 20 percent.

But official backpedaling is on the rise. The British government indicated Monday it would take a more cautious approach following an official report that raised multiple warnings about the technology, specifically that it contributes to high food prices and may create more greenhouse gas emissions than it prevents.

The European Parliament meanwhile is to vote later this year on a proposal to lower the EU target to just 4 percent by 2015, after a committee of lawmakers supported the measure Monday.

Rumblings of disaffection with biofuels have resonated from French politicians, who pooh-poohed the 10 percent target last week, to Germany, where the government has scrapped tax breaks for green fuels.

“It would be foolhardy at the moment on the evidence that we have got to say we should go headlong in pursuit of biofuels,” Ed Gallagher told the BBC. He’s the author of the British report, which called for Britain’s own targets to be reduced. “At the moment, on the evidence that we have got, getting to 10 percent is going to be very difficult without causing environmental damage and an effect on food prices.”

Adrian Bebb of Friends of the Earth adds: “The political tide in Europe is turning against biofuels. Everyone realizes that it’s a crazy idea to use valuable land to grow crops for cars and not people. We are starting to see a pretty big retreat.”

Europe was an early adopter of biofuel targets and an eager producer of biodiesel (derived from plant oils, as opposed to ethanol which is derived from sugar and corn). In a continent that prides itself on its green credentials, political leaders were eager to make firm commitments to technology that could help combat climate change and reduce Europe’s dependency on energy imports.

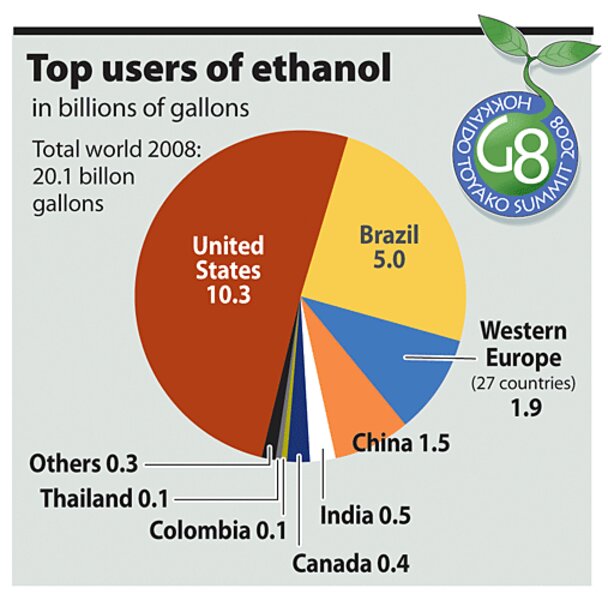

But that determination has been sorely tested by the contention that devoting land to biofuels compounds a worldwide food shortage that has sent prices soaring and pushed millions of people into hunger. In a sign that global scepticism towards biofuels is growing, the G-8 nations as well as Mexico, Brazil, China, India, and South Africa insisted Tuesday at the G-8 summit in Japan that biofuels must be compatible with “food security.”

A World Bank report leaked to a British newspaper last week estimated that biofuels were responsible for 75 percent of the recent spike in global food prices, which have risen more than 80 percent in the past three years.

US Agriculture Secretary Edward Schafer said recently that biofuel production has pushed up global food prices by only 2 or 3 percent. and that biofuels had cut US consumption of oil by a million barrels a day.

World Bank President Robert Zoellick said at the G-8 meeting that both Europe and the US should look at reducing biofuel targets. The Bush administration has a target of cutting gasoline use by 20 percent by 2017, primarily by stepping up the use of ethanol.

And yet targets remain vital to give the nascent industry a stimulus to compete with Big Oil. Giles Clark, the editor of Biofuel Review, a newsletter in Britain, says that unless retailers are forced to supply certain quotas of the fuel, they won’t bother. “The oil majors have to be involved,” he says. “They have the forecourts [gas stations]. Why would they bother with biofuels unless there was some leverage? So there needs to be some encouragement.”

Plenty of EU officials remain convinced that biofuels should remain part of the mix. Michael Mann, EU agricultural spokesman, says that Europe could still hit its target “without major effects on food supplies,” and argues that biofuels have less of an impact on food prices than do failed harvests and burgeoning demand from a growing global population.

“The amount of corn the US is putting into ethanol does have an effect on the market,” he acknowledges. “But rice, for example, has seen the biggest increase in prices and it is not used for biofuels. Sugar is a biofuels crop – and its price has gone down.”

Mr. Mann dismisses arguments that some biofuel production can actually generate more greenhouse gases, saying that all EU biofuels must be at least 35 percent cleaner than fossil fuels to qualify as such.

Other experts argue that even if Europe retreated or paused in its “dash for biofuels,” the impact on global food prices would be minimal. Abdolreza Abbassian, an economist at the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Rome, says “Unless some heavyweight like the US shifts policy, we probably will not see dramatic changes.” He estimates that the US has switched 30 percent of its corn output into biofuels.

Experts say that the future of biofuels probably lies not in edible plants now being used, but in nonedible crops – the so-called second generation biofuels.

Giles Clark says these biofuels fall into two categories: those that use the nonfood parts of plants, like stems and straw. Others are nonedible plants such as algae and jatropha which, says Clark, “can be grown on marginal land that wouldn’t support food crops, is native to Africa, is not a food plant at all.”