Surviving the first ‘deepfake’ election: Three questions

Loading...

Deepfakes – altered video or audio that seems convincingly real – raise questions about truth in the political process. With 2020 campaigns underway, two states have passed laws aimed at preventing deepfakes from influencing elections.

What exactly is a deepfake?

Deepfakes are made using deep learning technology, which uses computer algorithms to teach itself a task.

Why We Wrote This

In politics, where it can always be hard to decide what to believe, digitized deception adds a new twist. Two states are taking steps to help voters better trust what their eyes see.

Picture a rose. To create a likeness of a rose using this technology, you’d put pictures of roses and pictures of tulips (“not roses,” for comparison) into a deep learning application, downloadable from the web. The application identifies the rose’s distinguishing characteristics and uses that information to create a synthetic image. The program can hone the algorithm (and image) further by comparing pictures of real roses with the generated image and identifying the differences. The process repeats and is like a “personal trainer” for the software, says Michael Kearns, a computer and information science professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

Each time the program successfully identifies the differences between the synthetic rose and the real ones, the next fake it produces becomes more seemingly authentic. Soon, the difference between the synthetic image and the photos is indistinguishable to the eye.

This process, known as a generative adversarial network, can also be used with video and audio files. It underlies many sophisticated deepfakes.

Deepfake videos of celebrities, intended as comedy, began circulating on the internet in early 2018, but one of the original uses of deepfake technology was less benign. Deepfake sex videos, using the faces of celebrities, were exposed by a Motherboard report in December 2017.

How could deepfakes affect 2020?

Even before deepfakes, voters have needed to sort through disinformation, which has even come from campaigns themselves.

“You don’t need deepfakes to spread disinformation,” says Hao Li, an associate professor of computer science at the University of Southern California who worked on a federally funded project to spot deepfakes.

With advances in technology, however, Professor Li predicts that undetectable deepfake videos are between six and 12 months away – a period that corresponds roughly with the election season.

Considering how social media platforms were used to spread disinformation ahead of the 2016 election, Danielle Citron, a law professor at Boston University who studies deepfakes, warns that they might affect the political process. Deepfakes, she says, could undermine the legitimacy of an election.

Who should address political deepfakes?

Texas and California have passed laws aimed at limiting the influence of political deepfakes in recent months. Texas’ SB 751 and California’s AB 730 make it illegal to create a deepfake with the intent of injuring a political candidate or influencing an election or to distribute such a video close to an election.

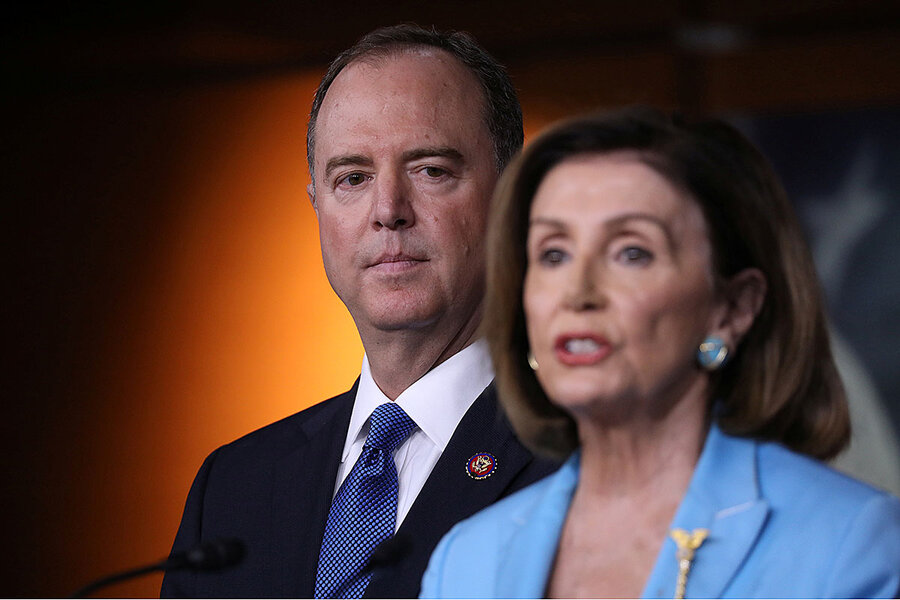

In June, the U.S. House Intelligence Committee held its first hearing to discuss manipulated media and deepfakes after House Speaker Nancy Pelosi was the subject of a “cheapfake” video, created by slowing down footage from a public talk to give the appearance that she was drunk. The video used basic video editing techniques, not deep learning, but was shared more than 2 million times on Facebook.

For individuals, not sharing or liking known fake or manipulated political content is a start. But insisting that candidates and elected officials do the same is another step.

Professor Citron, who testified before the House Intelligence Committee, co-authored an eight-point plan for presidential campaigns to adopt in advance of a deepfake crisis. Point 1: All candidates should issue a statement that says they will not knowingly disseminate fake or manipulated content and requests their supporters abide by the same commitment.

Professor Li points out that deepfakes are not inherently a bad thing. The discussions they generate should remind people to question what they see, check the facts, and consider the intention of a video, he says.

The best advice, however, might also be the most difficult to follow.

“Be ever vigilant,” says Professor Kearns.