Apple = $1,000,000,000,000

Loading...

| San Francisco

Apple is the world's first publicly traded company to be valued at $1 trillion, the financial fruit of stylish technology that has redefined what we expect from our gadgets.

The milestone reached Thursday marks the latest triumph of a trend-setting company that two mavericks named Steve started in a Silicon Valley garage 42 years ago.

Apple's shares gained $5.89 to close at $207.39, leaving the company's market value a notch above $1 trillion – around $1,001,679,220,000, according to FactSet. Apple sits atop a United States stock market that has become dominated by technology-centered companies: Amazon, Google's parent Alphabet, Microsoft, and Facebook round out the top five in market value.

The achievement seemed unimaginable in 1997 when Apple teetered on the edge of bankruptcy, with its stock trading for less than $1, on a split-adjusted basis, and its market value dropping below $2 billion.

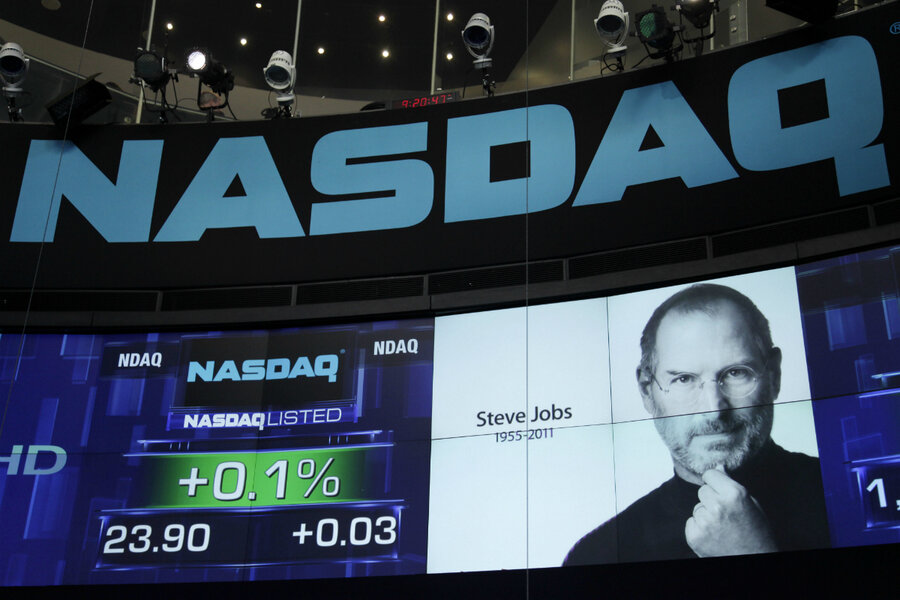

To survive, Apple brought back its once-exiled co-founder, Steve Jobs, as interim CEO and turned to its archrival Microsoft for a $150 million cash infusion to help pay its bills.

If someone had dared to buy $10,000 worth of stock at that point of desperation, the investment would now be worth about $2.6 million.

Jobs eventually shepherded a decade-long succession of iconic products such as iPhone that transformed Apple from a technological boutique to a cultural phenomenon and moneymaking machine.

The stock has been surging this week as anticipation mounts for the next generation of iPhone, expected to be released in September.

Although iPhone sales aren't rising as rapidly as they were a few years ago, Apple has been adding enough new features to persuade consumers to pay higher prices for its top-of-the-line devices. In its most recent quarter, Apple fetched an average price of $724 per iPhone – a nearly 20 percent increase from an average of $606 per iPhone at the same time last year.

The price escalation has widened Apple's profit margins to the delight of investors, who have boosted the company's market value by about $83 billion – nearly equal to the entire market value of American Express – since the quarterly report came out late Tuesday. The 9 percent gain was Apple's biggest two-day advance in nearly a decade.

Apple's stock has climbed by 23 percent so far this year, compared to a 6 percent gain for the Standard & Poor's 500 indexes.

The recent rally in Apple's stock contrasts sharply from a deep downturn in the fortunes of two social media companies, Facebook, and Twitter that offer some of the most popular apps used on iPhones and other mobile devices. User growth and engagement on Facebook and Twitter has been wavering amid deepening concerns about their ability to protect people's personal information and shield them from misinformation and other abuses that have been infecting their services.

As mighty as Apple may seem now, economic, and cultural forces can quickly shift the corporate pecking order.

Consider the plight of Exxon Mobil, which was the most valuable US company five years ago. Now, it ranks as the ninth most valuable, surpassed by Apple and a list consisting primarily of companies immersed in technology.

Some analysts believe e-commerce leader Amazon.com will supplant Apple as the world's most valuable company in the next year or two as its spreading tentacles reach into new markets.

And Saudi Arabian Oil Co., known as Saudi Aramco, is planning an initial public offering that Saudi officials have said would value the giant oil company at about $2 trillion. But until the IPO is completed, Saudi Aramco's actual value remains murky.

This much is certain: Apple wouldn't be atop the corporate kingdom without Jobs, who died in October 2011. His vision, showmanship, and sense of style propelled Apple's comeback.

But the recovery might not have happened if Jobs hadn't evolved into a more mature leader after his exit from the company in 1985. His ignominious departure came after losing a power struggle with John Sculley, a former Pepsico executive who he recruited to become Apple's CEO in 1983 – seven years after he and his geeky friend Steve Wozniak teamed up to start the company with the administrative help of Ronald Wayne.

Jobs remained mercurial when he returned to Apple, but he had also become more thoughtful and adept at spotting talent that would help him create a revolutionary innovation factory. One of his biggest coups came in 1998 when he lured a soft-spoken Southerner, Tim Cook, away from Compaq Computer at a time when Apple's survival remained in doubt.

Mr. Cook's hiring may have been one of the best things Jobs did for Apple. As Jobs' top lieutenant, Cook oversaw the intricate supply chain that fed consumers' appetite for Apple's devices and then held the company together in 2004 when Jobs was stricken with cancer that forced him to periodically step away from work – sometimes for extended leaves of absences.

Just months away from his death, Jobs officially handed off the CEO reins to Cook in August 2011.

Cook has leveraged the legacy that Jobs left behind to stunning heights. Since Cook became CEO, Apple's annual revenue has more than doubled to $229 billion while its stock has quadrupled. More than $600 billion of Apple's current market value has been created in that time.

Cook hasn't escaped criticism, however. The Apple Watch has been the closest thing that the company has had to create another mass-market sensation under Cook's leadership, but that device hasn't come close to breaking into the cultural consciousness like the iPhone or the iPad.

That has raised concerns that Apple has become far too dependent on the iPhone, especially since iPad sales tapered off several years ago. The iPhone now accounts for nearly two-thirds of Apple's revenue.

But Cook has capitalized on the continuing popularity of the iPhone and other products invented under Jobs' reign to sell services tailored for the more than 1.3 billion devices now powered by the company's software.

Apple's services division alone is on pace to generate about $35 billion in revenue this fiscal year – more than all but a few dozen US companies churn out annually.

Apple had also come under fire as it accumulated more than $250 billion in taxes in overseas accounts, triggering accusations of tax dodging. Cook insisted what Apple was doing was legal and in the best interest of shareholders, given the offshore money would have been subjected to a 35 percent tax rate had if it were brought back to the US.

But that calculus changed under the administration of President Trump, who pushed Congress to pass a sweeping overhaul of the US tax code that includes a provision lowering this year's rate to 15.5 percent on profits coming back from overseas.

Apple took advantage of that break to bring back virtually all of its overseas cash, triggering a $38 billion tax bill. All that money coming back to the US also spurred Apple to raise its dividend by 16 percent and commit to buying back $100 billion of its own stock as part of an effort to drive its stock price even higher.

This story was reported by The Associated Press.