At first, the idea of a rapid transportation system that would allow people to move from city to city through an enclosed tube at speeds of up to 700 miles per hour, which Musk introduced in 2013, invited skepticism.

Was the proposal – which would allow people to make the trip from San Francisco to Los Angeles in as a little as half an hour – just a space-age pneumatic tube?

Dismissing comparisons to California's plans to build a high-speed bullet train like those found in much of Europe and Japan, Musk argued in a white paper that an enclosed tube could be more efficient than either high-speed rail or a supersonic plane for trips between cities located relatively close together, convincing scientists and engineers that the project could potentially work.

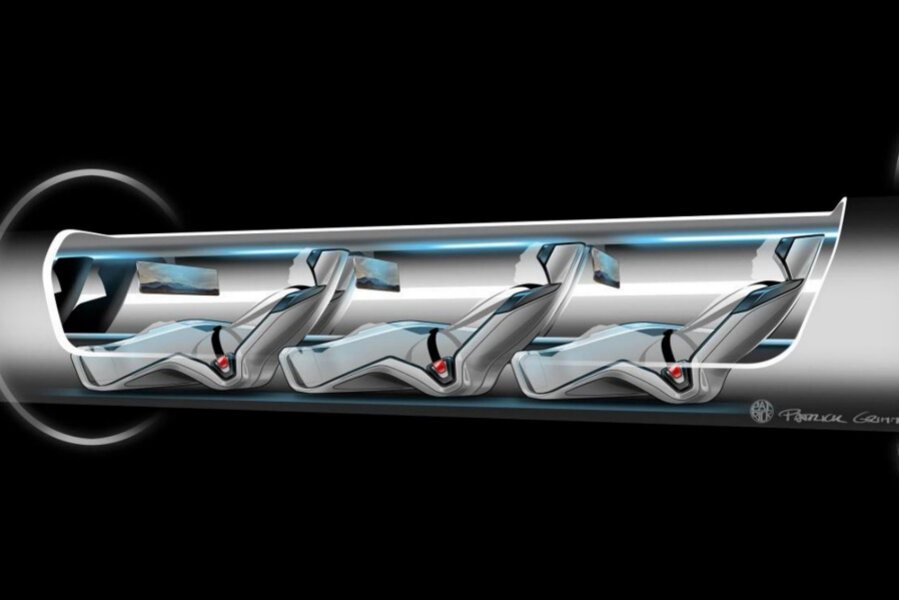

The Hyperloop would work by reducing the pressure inside a straight tube, then shooting a capsule through it at very high speed, allowing it to glide through the tube on a thin layer of air, much as a puck floats on an air-hockey table. An air pump mounted on the capsule's nose would reduce drag. Musk has also said the system could be self-powered, using a combination of solar panels and battery packs.

In December 2015, a group of engineers announced plans to test a prototype version using a specially-built electric motor on a 1-kilometer test track in Las Vegas currently under construction. The company, Hyperloop Technologies, isn't directly affiliated with Musk's SpaceX, while a second company, Hyperloop Transport Technologies, is also building its own test track.

Separately, SpaceX announced a design competition of its own, selecting 124 teams of mostly student engineers from 20 countries and 27 US states to compete to design the pods that travel through the tube in the company's own test, set for summer 2016 at SpaceX's headquarters near Los Angeles.

The winning teams will also face the additional challenge of having to find a sponsor to build a prototype of their design.

“This is one of the problems where if you don’t tell the students it’s impossible they’ll figure out a way to do it," Gregory Chamitoff, an astronaut and professor of engineering at Texas A&M told Ars Technica in December 2015.

As with many of Musk's projects, the cost of building the Hyperloop is still up in the air. He's said building the pods and motors that will propel them along the tracks would be relatively inexpensive, costing "several hundred million dollars," while building the tube, which would be raised on pylons along major highways, could cost several billion dollars, Ars Technica reports.