In coding classes, Boston schools aim to provide 21st century skills

Loading...

| Boston

On the projector screen, in front of an animated house, several figures are constantly in motion. A cat and a bear pop in and out of the frame, as a dancing Batman and a cartoon representation of the rapper Snoop Dogg glide forward, stopping momentarily before darting backward.

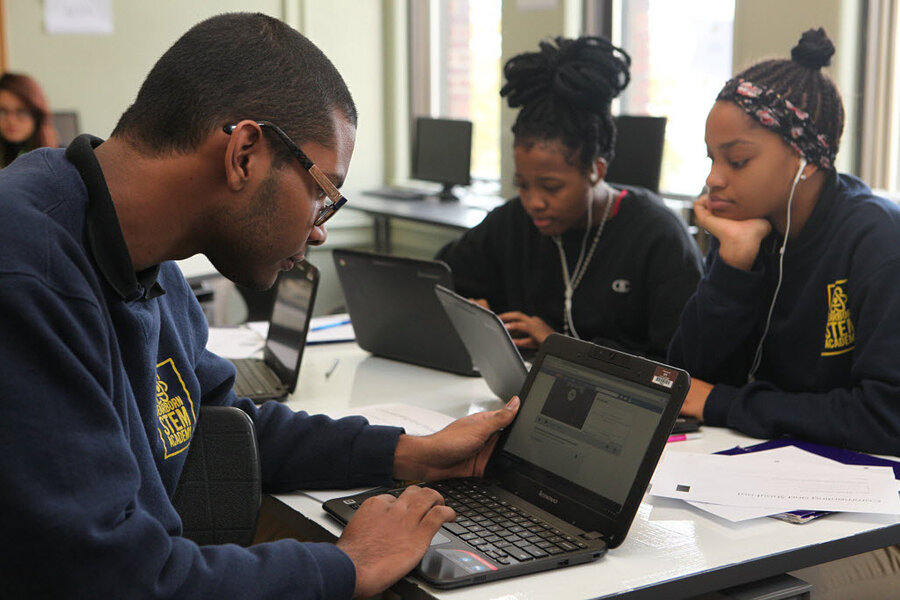

Sitting at tables around the screen, the 9th grade students at Dearborn STEM Academy in Boston watch the dancing figures closely.

At first, it looks like an animated movie. But then the class’s teacher, Jonathan LoPorto, opens a new tab, revealing rows of multicolored blocks in Scratch, the computer programming software that controls the figures, known as sprites.

“What does this script make the sprite do?” he asks, pointing to a series of numbers and statements on the screen. ”How’s it going to dance, and exactly what is it going to do?”

Around the room, students’ hands shoot up excitedly. “It was gonna, like, go to a certain spot, back and forth,” one student says.

“How do you know what spot?” the teacher asks.

“Because it says go to ... 16 on the x-axis and negative 2 on the y-axis, in a way it’s going to keep going back to that spot, and then keep going back and forth,” she replies.

At Dearborn, a Boston public school long centered in the city’s Roxbury neighborhood, programming classes such as this one are a requirement, offered at several levels for students in grades 6 through 12.

The computer science courses are part of a broader effort among school officials to introduce technology into classrooms in order to provide Boston’s students with technical skills for a rapidly changing job market.

"An incredible treat"

The effort to introduce technical curricula has spread across the country. In New York City, for example, Mayor Bill De Blasio unveiled a plan last month to have all public schools in the city offer computer science courses by 2025, promising $81 million to achieve that goal.

“I’ve never been in a school where technology’s even been offered, so this is such an incredible treat,” says Lisa Gilbert-Smith, Dearborn’s new principal, who has been working in the district for 20 years. “Our goal is definitely that we’ll be able to get folks jobs before they leave high school. That’s definitely our vision that we’ll start with our sixth graders. We want to make sure that our kids ... have marketable skills, that they actually can get work in the technology field, and that they’re exposed to technology to utilize in whatever careers they eventually choose in their lives.”

The impact of the classes is particularly striking at Dearborn STEM, district officials say. The school, which had 258 students last year from Roxbury and Dorchester – including many Cape Verdean students, for whom English is a second language – was rumored to be a candidate for state takeover or conversion to a charter school.

But after parents and community members fought a long-running battle to keep the school open, local education nonprofit BPE (formerly the Boston Plan for Excellence) took over the school in July as part of a negotiation with the district. BPE, a three-decade-old organization that trains teachers through its Boston Teacher Residency Program, began its first classes at Dearborn this fall.

“As far as the students go, it’s unlike everything you’ve ever seen because the students are actually learning a lesson that is applicable to what they do on their personal time,” says Mark Racine, the district’s chief information officer. “I taught fifth grade and I can’t tell you how painful it is to teach these subjects when [students] don’t see how they are related to their personal lives.”

The school is currently housed at the Jeremiah Burke High School building in Dorchester while a new $72 million building with expanded classroom space and lab facilities is being built on Greenville Street in Roxbury.

In addition to offering a wide range of technical classes, the school also plans to introduce an 11th grade internship program aimed at providing students with work experience at local technology firms.

Boston’s efforts come as a national debate continues to rage over technology’s role in the classroom, particularly due to a growing $8 billion educational technology sector, which some critics have argued has pushed technology into classrooms too quickly.

“One thing we have found is that it can be more challenging to integrate technology into classrooms in low income communities,” says Mark Warschauer, a professor of education at the University of California, Irvine, whose research has focused on the impact of One Laptop Per Child, a 10-year-old initiative to provide low-cost, low-powered laptops to countries in the developing world and the US.

“A lot of these communities have higher teacher turnover, administrator turnover, fewer technology-savvy parents, more kids with weaker English language skills,” he says. “If you just throw technology into schools without the proper social support, technology can amplify inequality.”

At other schools that are embracing new models of teaching students – such as more intensive small-group or one-on-tutoring – figuring out how to best make use of newer technologies is still an ongoing challenge.

"We'll turn out the lights if it isn't working for kids"

One day in September, a 6th grade classroom in Boston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood bustles with activity. Students sit in small groups working on a series of math worksheets, guided by tutors who looked carefully over the packets, occasionally working with students using a laptop.

MATCH Next, a new 5th and 6th grade campus that is part of the MATCH charter school network that began with a high school in 2000, revolves around close interaction between students and tutors, both inside and outside of the classroom.

“Everyone works on a packet in the morning, then tutors stop and see how everyone’s doing,” says Ray Schleck, the school’s principal. Tutors serve particularly as a contact for parents, calling to check in on students once a week.

While the school has focused particularly on changing the traditional lecture-driven mode of classroom instruction, it has been cautious about introducing technology, focusing first on ensuring students are learning basic skills.

“We’re an ed-innovation platform, but never, ever at the expense of student learning,” says Orlando Watkins, MATCH’s executive vice president, who focuses on the charter school's development and communications. “I don’t know if it’s the case at every charter, but certainly at MATCH, it’s the right type of environment to phase in innovation."

But, he adds, “We’ll turn off the lights if it isn’t working for kids.”

The school uses software such as Google Classroom – a suite of education apps aimed at students and teachers. However, MATCH uses it primarily for teachers to schedule and exchange lesson plans. “Disproportionately, we’re skeptical people,” says Mr. Schleck. Technology like Google Classroom “saves us a lot of time and energy on organizing materials. We’ve had buckets with more success than others," he says. But software that focuses on teaching hasn’t been as successful.

The school uses exercises developed by education software provider Khan Academy to teach math, but has found that a series of videos created by the company has been less helpful than traditional lessons created by each teacher.

But that may change over time for the school – which nearly tripled its enrollment this year to serve 146 students in 5th and 6th grades.

“If a school has a baseline culture of being productive, technology is very helpful,” he says. “I think we’re trying to learn what the right place of technology is.”

The impact of ed-tech

At times, the debate over whether classroom technology can truly reduce inequality has boiled over into the mainstream. This fall, the Los Angeles Unified School District abandoned a $1.3 billion effort to provide an iPad for every student, teacher, and administrator after reports that teachers barely used software provided by industry giant Pearson.

In September, the OECD put out a report that found that computers in education could have a mixed impact. “Perhaps the most disappointing finding of the report is that technology is of little help in bridging the skills divide between advantaged and disadvantaged students,” its executive summary noted.

But Professor Warschauer at UC Irvine says that computers are often helpful in particular contexts that encourage analytical thinking, such as allowing students to write and revise their work, share it with teachers and classmates, and conduct online research. But integrating technology into educators’ own curricula so they can use it in the classroom is still an ongoing challenge.

“I think teachers need to really think about and learn about and have chances to practice about the role of technology in instruction,” he says. “It’s not so much that tech needs to be a separate thing, it really needs to be integrated in, we don’t have separate courses on how to use pencils and pens, these things have been integrated into the curriculum.”

As the Dearborn students split off to begin their own individual dance party projects using Scratch, Mr. LoPorto, the class’ teacher, pauses to reflect on the program.

In a recent computer science survey course, he says, a classroom discussion about Google’s introduction of self-driving cars led to a conversation about the future of related industries. What if there were no taxi drivers, students asked? What if the cars caused fewer accidents, meaning less work for body shops? By providing computer science training early, the school aims to provide exposure to alternative career paths.

“That’s a really hard reality, and so rather than switching gears on them senior year of high school, I’d like to switch gears on them in 6th grade, and prep 'em the best that we possibly can for what is coming,” LoPorto says. An ongoing challenge, he adds, is engaging students who come in with differing amounts of experience with computers.

Ms. Gilbert-Smith, the school’s principal, says that for an increasingly tech-savvy generation, there is a broader goal: ensuring they learn more about how computer programming works, and hopefully increasing their confidence to use technological tools.

“Those are the classes that it seems like everybody wants more of,” she says. “We had a group of students that went on a field trip, and they’re not supposed to be back until after school, and they’re like ‘We might get back early – can we still go to technology class?’ ” she adds, laughing. “They’re super excited about going to technology classes.”